The Lens, the Canvas, and the Soul: A Personal Journey Through Photography as Fine Art

I remember a time, not so long ago, when the very idea of photography being "fine art" felt... well, a bit like calling instant noodles gourmet. It wasn't a conscious dismissal, but rather an inherited bias. There was this quiet whisper from the hallowed halls of art history – the Royal Academies, the Salon system – suggesting that true art demanded paint, brushes, and a certain kind of struggle. It had to be a tangible, hand-wrought effort, like chiseling marble into a sculpture or painstakingly laying mosaic tiles. The idea that a machine could create 'art' just didn't fit neatly into that established narrative. It felt like a defiance of the very human touch, the laborious craft that had defined centuries of artistic tradition.

But, as with many deeply held, unexamined beliefs, life—and a particularly striking photograph that caught me off guard—had a way of making me reconsider everything. It was a visceral moment where a simple image transcended its mechanics and spoke directly to something inside me. Have you ever looked at a photo and felt it resonate deep within you, more than just recognizing the subject? That's when the shift began for me. It wasn't about the gear or the perfect exposure; it was about the soul peering back through the lens, echoing my own artistic quest.

This article is a journey, tracing photography's hesitant evolution from a mere scientific curiosity to a revered, emotive art form that now hangs proudly in galleries, often right next to my own abstract paintings. It's a story of transformation, both for the medium itself and for my own perception, a parallel path from initial skepticism to profound appreciation.

Chapter 1: The Machine's Eye – Capturing Reality, Challenging Tradition (1839 - Late 19th Century)

What happens when a machine dares to mimic the human eye? Long before the famous mid-19th century breakthroughs, pioneers like Nicéphore Niépce were already wrestling light onto plates, achieving the first permanent photograph, a heliograph, as early as 1826. But it was Louis Daguerre with his glistening daguerreotypes, and William Henry Fox Talbot with his reproducible calotypes and salted paper prints, who truly brought photography to public attention. Their intentions were largely practical: capturing reality with unprecedented accuracy. Imagine the sheer wonder! Before this, visual records were limited to painstaking hand-drawn illustrations, engravings, or paintings, often filtered through an artist's subjective interpretation or requiring immense time. Suddenly, the world could be recorded almost instantaneously, with an objective detail previously impossible. It was revolutionary, yes, but artistic? Many scoffed. "How can a machine truly feel?" they seemed to ask, dismissing the cold mechanics.

Beyond its initial wow factor, early photography found immediate, pragmatic applications. It became invaluable for scientific documentation, capturing everything from astronomical observations to medical conditions with dispassionate precision. And for the burgeoning middle class, it offered an affordable alternative to painted portraits, creating a visual record of family and identity previously out of reach. Yet, this very utility, this cold, mechanical objectivity, became a point of contention for the art world.

The debate was fierce. How could a machine-made image, produced by chemicals and light, possess the creative spirit of a hand-painted masterpiece? Artists, understandably protective of their craft, saw it as a threat, a soulless reproduction. I get it; there's a natural human tendency to resist anything new that challenges established norms. We love our comfort zones, don't we? It reminds me a bit of how some purists still struggle with certain contemporary art forms, a reluctance to expand their definition of what art can be, much like the initial resistance to even the history of abstract art centuries later. We often want art to fit neatly into predefined boxes.

Chapter 2: Pictorialism – Donning a Fancy Suit for Acceptance (Late 19th - Early 20th Century)

What if photography just tried to fit in? In an attempt to appease the critics and elevate photography's status, a movement called Pictorialism emerged. These photographers, like the influential Alfred Stieglitz (before his later evolution) and the pioneering Julia Margaret Cameron, actively sought to make their photographs resemble paintings. They used soft focus, manipulated negatives, and printed on textured papers, often employing labor-intensive techniques like gum bichromate or platinum prints to achieve painterly effects. Their subjects often mirrored academic painting: romantic narratives, allegorical scenes, idealized portraiture, or evocative landscapes. Beyond Stieglitz and Cameron, figures like Gertrude Käsebier, known for her evocative portraits, and Clarence H. White, with his softly rendered domestic scenes, pushed this painterly aesthetic, even exhibiting in painting salons or parallel exhibitions like the Salon des Refusés of the photographic world, aiming to prove their artistic legitimacy.

It was almost as if photography was trying to put on a fancy suit, hoping to be invited to the exclusive art party. This era fascinates me because it perfectly illustrates the pressure to conform for acceptance. As an artist, I've often felt that very pull – the subtle (or not-so-subtle) pressure to create work that's 'palatable,' easily categorized, or that fits a market trend, sometimes at the expense of my own raw authenticity. I recall a period early in my career where I tried to mimic popular styles, thinking that was the path to validation. But true artistic growth, as I've found on my artist's timeline, often comes from daring to be different, from embracing the discomfort of standing apart, not just being better at imitation.

Yet, for all its efforts to conform, Pictorialism faced its own criticisms. Many purists and a new generation of photographers found its imitation of painting to be a creative cul-de-sac, arguing that the medium's true potential lay elsewhere. This mimicry, this desperate plea for acceptance, couldn't last forever. A growing dissatisfaction simmered, leading to a bolder, more authentic assertion of photography's unique vision – a quiet rebellion brewing just beneath the surface, ready to burst forth and reclaim the camera's inherent power.

Chapter 3: Modernism and the Straight Photograph – Embracing Photography's Unique Qualities (Early - Mid 20th Century)

What if the machine didn't have to pretend to be human? Then came the rebellion, the moment photography truly found its voice, asserting its independence. Alfred Stieglitz, in a remarkable pivot from his Pictorialist past, became one of its most ardent champions. He realized photography didn't need to imitate painting; it had its own unique strengths. This philosophy birthed "straight photography" – an embrace of sharp focus, rich tonal range, and unmanipulated images that celebrated the camera's inherent ability to render detail and capture light in its purest form. This movement was deeply influenced by the burgeoning modernist art movements like Bauhaus and Constructivism, which championed functionalism, clear forms, and an honest engagement with materials. These principles—objectivity, geometric precision, and an almost industrial aesthetic—found a natural home in straight photography's stark realism, asserting that the medium's inherent qualities were artistic in themselves.

A pivotal group in this shift was Group f/64, founded by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and others. Their manifesto championed "pure" photography, rejecting soft focus and painterly effects in favor of maximum sharpness and detail. Adams, whose majestic landscapes defined the genre with their stark contrasts and incredible detail, often achieved through his precise Zone System for exposure and development, was a key figure. Weston, with his meticulous still lifes—like his iconic peppers—elevated everyday objects to sculptural forms, revealing their abstract beauty through pristine focus. Other pioneers like Paul Strand also championed this approach, transforming everyday scenes into powerful, abstract compositions.

What did 'straight photography' look like? Think crisp focus, rich tonal range from deep, velvety blacks to sparkling whites, and an almost brutal honesty in rendering textures and forms without embellishment. This wasn't about mimicking; it was about mastering the medium, letting the camera speak in its own, powerful visual language. It’s that beautiful moment when you realize you don't need to follow the crowd, that your authentic self, or in this case, your authentic medium, is powerful enough. It’s a bit like when I finally stopped chasing trends in my own work and truly embraced my unique approach to abstraction, finding my own abstract art style that resonated with my inner vision.

Chapter 4: Post-War and Contemporary Approaches – Blurring Lines and Expanding Horizons (Mid 20th Century - Present)

What happens when the art world finally sees photography? Once photography shed its inferiority complex, thanks to the bold declarations of straight photography, there was no stopping it. Post-World War II, photography firmly entered the hallowed halls of galleries and museums. Curators and critics began to recognize its profound capacity for expression, narrative, and conceptual depth, and importantly, its unique ability to capture fleeting moments and provoke immediate emotional responses, often with a stark honesty unlike any other medium.

We started seeing artists like Cindy Sherman challenging identity with her conceptual self-portraits that explore female roles and representation, dissecting the gaze and societal archetypes. Andreas Gursky created monumental, often unsettling, vistas that critique globalization and modern life through a detached, almost abstract lens, drawing attention to patterns of consumption and organization. Jeff Wall staged cinematic tableaux that blur the lines between photography, painting, and film, infusing everyday scenes with a heightened, theatrical drama. And Wolfgang Tillmans explored the everyday with a conceptual, almost abstract eye, often blurring the lines between art and documentation, elevating seemingly casual snapshots to profound observations. Photography also emerged as a powerful tool for social commentary and activism, forcing difficult truths into public view and sparking dialogue – a role that undeniably contributed to its growing artistic gravitas. Furthermore, the 20th century saw photography become a dominant force in advertising, a commercial application that paradoxically forced a re-evaluation of its artistic potential, as curators began to distinguish between its utilitarian and expressive forms. Beyond these, photography became central to many conceptual art movements where the idea or process behind the image often outweighed the aesthetic beauty of the print itself, pushing boundaries of what art could be.

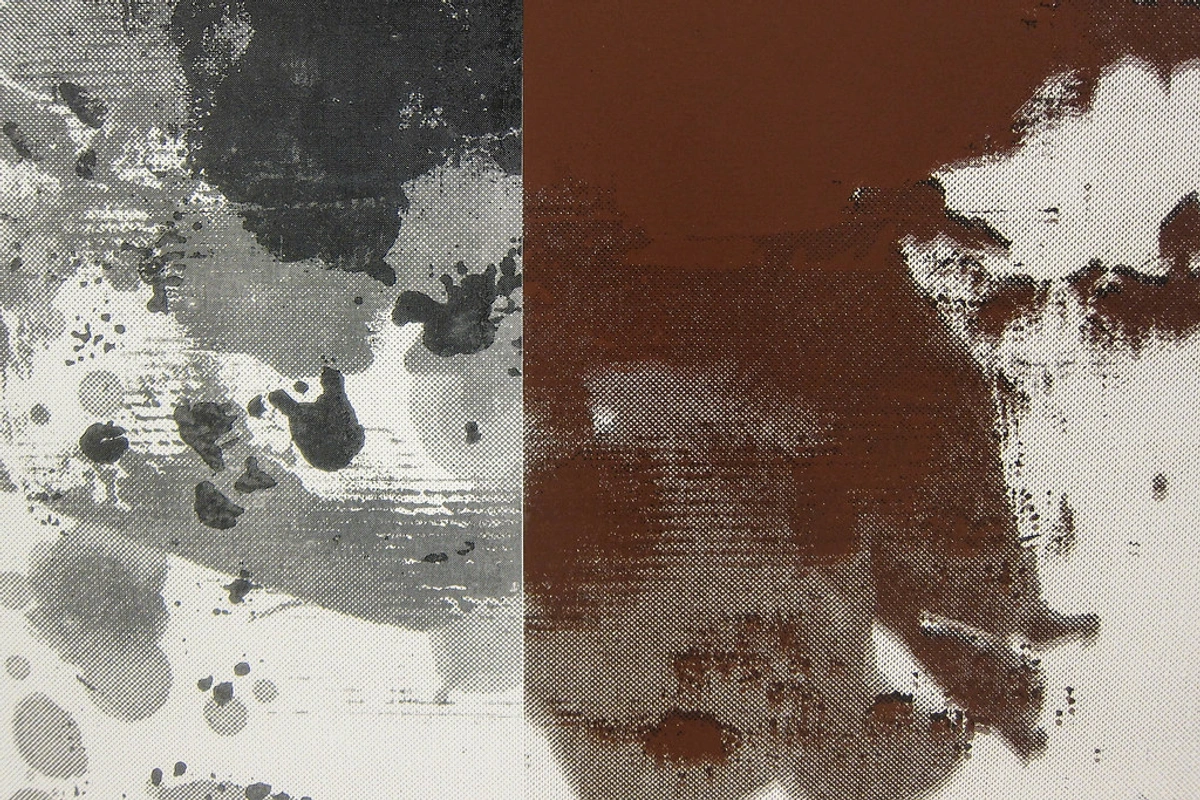

The digital revolution, which I'll admit I initially viewed with a healthy dose of skepticism (I'm a creature of habit! I still sometimes yearn for the darkroom's chemical smell, but who am I kidding, I often prefer the tangible mess of paint on my studio floor to pixels on a screen), only accelerated this evolution. Suddenly, the possibilities for manipulation, for creating entirely new realities, were endless. While it brought new debates about authenticity and the very nature of truth in an image, challenging the old idea of photography as an objective record, it also pushed the boundaries of what a photographic image could be. For me, as an abstract painter, this blurring of lines is incredibly fascinating. My own work, with its layers of color, texture, and often fragmented forms, seeks to evoke emotion and suggest narratives rather than depict literal reality. Much like a contemporary photographer who might digitally manipulate an image or stage a scene to achieve a particular conceptual effect, I'm using my medium to explore ideas and feelings that exist beyond the visible surface. The digital realm, with its new brushes and colors, feels like another vibrant extension of this creative freedom. It undeniably cemented photography's place not just as a recording device, but as a powerful tool for artistic expression, sitting comfortably alongside other forms of contemporary art like the expressive abstractions of Christopher Wool or the complex, layered paintings of Gerhard Richter, because the intent behind the image, not just the technical process, is what truly defines it as art.

The Enduring Power: Why Photography Matters as Fine Art

So, why does any of this matter to you and me, beyond a dry art history lesson? Because photography, now firmly established as fine art, offers a unique window into the human experience. It captures fleeting moments, documents profound changes, and can evoke emotions with an immediacy that other mediums sometimes struggle to match. It possesses a unique ability to elevate the ephemeral and the mundane – think of a captivating street photograph that turns an ordinary passerby into a profound narrative, or a close-up of a common object transformed into an abstract sculpture. Photography transforms these everyday elements into subjects of profound artistic contemplation. It's democratic in its accessibility (almost everyone has a camera now!), yet deeply complex in its artistic potential. This very accessibility, however, also presents a fascinating challenge for photographers striving to be recognized as fine artists in a saturated visual world, demanding even greater vision and conceptual depth.

When I create my own paintings – whether they're vibrant canvases or subtle explorations of form – I'm intensely focused on composition, color, and emotional impact, much like a photographer carefully frames a shot, deciding what to include and what to leave out, what feeling to emphasize. It's a parallel creative process, and a reminder that the art I create and offer for sale shares this same dedication to vision. If this journey has sparked an interest, perhaps you're even considering collecting photography as fine art yourself. The journey of photography reminds me that art is not static; it's a living, breathing entity that constantly evolves, challenges, and redefines itself. And that's a beautiful, sometimes uncomfortable, truth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Have more questions swirling in your mind? It's natural! Here are some common thoughts and their answers:

When did photography become recognized as fine art?

While photography emerged in the mid-19th century, its recognition as a legitimate fine art form was a gradual and often contentious process, evolving over many decades. Early attempts came with Pictorialism (late 19th century), which sought to make photographs resemble paintings. The most significant shift occurred in the early 20th century with "straight photography," championed by artists like Alfred Stieglitz, who passionately argued for photography's unique artistic merits, distinct from painting. It wasn't until the mid-20th century that photography became more widely accepted into major galleries and museums, solidifying its place, though debates about its precise artistic status continue even today in some circles, reminding us that art's definition is always in flux.

What is the difference between documentary and fine art photography?

Documentary photography primarily aims to record events, people, or places for informational or historical purposes, often with a journalistic intent, focusing on factual reporting. Think of images capturing a historical event or social issue, like Dorothea Lange's poignant Depression-era photographs. Fine art photography, on the other hand, is created primarily to express the artist's vision, emotions, or ideas, focusing on aesthetic and conceptual qualities. An example might be an abstract photograph where the subject is less important than the interplay of light, shadow, and form, or a conceptual piece designed to provoke thought. While there can be overlap, and some documentary work achieves fine art status, the underlying intent behind the creation is key.

Who are some pioneers of fine art photography?

Key pioneers include Julia Margaret Cameron (a Pictorialist known for her ethereal, often allegorical portraits that captured a soulful depth), Alfred Stieglitz (pivotal in moving towards "straight photography" and promoting photography as art through his influential galleries and journals), Edward Weston (a master of still life, known for finding abstract forms in nature and meticulous compositions), and Ansel Adams (a key member of Group f/64, celebrated for his majestic landscapes and the precise Zone System). Other important figures include Paul Strand (known for his precisionist images of everyday life, championing the camera's objective eye), Imogen Cunningham (celebrated for her botanical studies and nudes with stark clarity), and Man Ray (a Surrealist who used experimental photography to push boundaries of abstraction and concept). In later eras, artists like Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, and Wolfgang Tillmans pushed conceptual and aesthetic boundaries, further cementing photography's place in fine art.

How does digital photography fit into fine art?

Digital photography has expanded the possibilities for fine art immensely. While some initially debated its "authenticity" due to ease of manipulation, and ethical considerations around truth and alteration remain, it has become fully embraced. Digital tools allow for unprecedented control over image creation, editing, and output, enabling artists to realize complex visions that might have been impossible with traditional film. It's just another set of powerful tools in the artist's arsenal, allowing for entirely new forms of photographic expression, from hyper-real composites to purely abstract digital creations.

Conclusion: A Moment Captured, a Story Told

The journey of photography from a mere record-keeper to a celebrated fine art medium is a testament to human creativity's boundless nature. It reminds us that "art" is less about the tools and more about the vision, the intention, and the connection it forges with the viewer. When I step back from my easel, paint-splattered and lost in thought, the core of my abstract work—the composition, the emotional landscape, the attempt to capture something intangible—feels intimately connected to the photographer's struggle to frame a moment, to distill essence. Next time you glance at a photograph, whether it's on a gallery wall or in a book, take a moment. Look beyond the subject. Ask yourself, what is the artist trying to say? What emotion is being evoked? You might find, as I did, a whole new world opening up. Perhaps it will even inspire you to experience art, whether photographic or painted, in person – or better yet, to ponder these very conversations about art's evolving nature at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch, a place where new perspectives are always welcome and where I hope to see you.