Ethical Art Collecting: Integrity, Provenance & Purpose

Navigate the complex world of ethical art collecting with this comprehensive guide. Explore provenance, fakes, artist support, AI art, sustainability, and making a positive impact on the art world.

Ethical Art Collecting: A Journey of Conscience and Curation

It’s easy to get lost in the sheer beauty, the vibrant colors, the raw emotional punch of a masterpiece, isn't it? As an artist who channels the chaos of my mind into abstract, colorful pieces, I see art's power firsthand. But for collectors, the journey isn't always so straightforward. It’s not just about what visually moves you; it's a deep dive into ethics, history, and responsibility. I remember once, almost buying a piece purely for its aesthetic appeal, then stopping dead when the whisper of its past started to feel heavier than the artwork itself.

The art world is a labyrinth of decisions, and honestly, some of them can keep you up at night, turning you into an amateur art detective. (My own detective skills are usually reserved for finding that one rogue tube of cadmium red, but for art, it’s a whole different ballgame!) It's like finding a beautifully wrapped gift on your doorstep – immense joy, until a tiny voice asks, 'Is this truly mine, or was it meant for someone else?' You wouldn't want to unknowingly keep something stolen, would you? The art world is no different. So, let's pull back the curtain on the ethics of art collecting, not as some dry academic exercise, but as a genuine conversation between people who love art. This isn't just about what to collect, but how to collect with integrity, understanding the hidden narratives, and making choices that resonate with your conscience. In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore both the philosophical underpinnings and the practical steps you can take to build a truly ethical collection that reflects your deepest values, making a positive impact on the art world and beyond—a journey that touches on history, fair exchange, the very definition of creativity, and our planet's well-being.

The Echoes of History: Provenance and Cultural Heritage

Every piece of art I create has its own clear beginning. But for many artworks, especially older ones, that story gets murky. Provenance, essentially the history of ownership of a work of art, is probably the first ethical consideration that pops into a collector's mind. And for good reason.

Imagine falling head-over-heels for an ancient artifact, a stunning sculpture, or a piece of tribal art. Your heart says, "Yes!" But your brain should immediately kick in with, "Wait, how did this leave its place of origin?" Many historical pieces carry the heavy burden of colonial exploitation, wartime looting (think of the countless artworks seized during World War II, like the Gurlitt hoard, or the ongoing discussions around the Elgin Marbles and Benin Bronzes), or illicit excavation. We can also look at prominent global debates surrounding pieces like the Rosetta Stone or the Parthenon Sculptures, which highlight the complex, enduring legacies of colonial acquisition and calls for repatriation.

These aren't just historical footnotes; they represent a deep wound to cultural identity, a painful separation of heritage from its rightful stewards. Repatriation, in these contexts, isn't simply about returning an object; it's about acknowledging historical injustice, restoring cultural continuity, and enabling communities to reclaim their narratives and sacred connections. Beyond these well-known examples, contemporary artists from indigenous cultures are actively engaging with themes of cultural reclamation and historical justice through their work. By supporting these artists, collectors can contribute to ongoing dialogues and empower communities to tell their own stories.

Beyond these well-known examples, there's a vital, ongoing ethical layer when collecting from living indigenous cultures and traditional communities. This means understanding and respecting the significance of sacred objects, traditional knowledge, and community-based ownership structures. Acquiring such pieces without proper consultation and respect for cultural protocols isn't just a misstep; it actively perpetuates a history of cultural erasure, stripping communities of their heritage and severing vital ties to their past and future. It's like admiring a beautiful rare bird, only to realize it was snatched from its nest. The beauty remains, but the context is painfully compromised. How do we reconcile our desire for beauty with the potential for historical injustice? When I encounter a piece with a whispered, rather than documented, past, my internal dialogue often becomes a dramatic monologue. I've personally walked away from pieces I genuinely loved, just because the whispers of a compromised past were too loud, and my conscience wouldn't let me overlook them. It's a tough decision, but one that ultimately feels right. We've actually got a whole article dedicated to these tough choices: Ethical Considerations When Buying Cultural Art. It’s a vital read if you’re looking to collect pieces with deep cultural roots, and for a deeper dive into tracing ownership, check out Understanding Provenance: Tracing the History of Your Abstract Art Collection.

So, what can you do? Research, research, research. Ask for full provenance documentation. A reputable dealer should provide this willingly. If they balk (meaning, they hesitate or refuse), or the story feels incomplete, it's a huge red flag. This also extends to collecting from private collections; even if a piece isn't from an archaeological site, its journey through private hands, especially those involved in regions of conflict or instability, needs thorough scrutiny. Sometimes, the most ethical choice is to admire from afar, or to support contemporary artists from those cultures who are telling their own stories. The goal is to ensure a transparent, consented, and ethically sound chain of custody from creator to collector. So, the next time you're captivated by an older piece, take a moment to consider its journey. What story does its provenance tell you? And sometimes, that story isn't just murky; it's completely fabricated, leading us into the shadowy corners of fakes and forgeries...

The Shadowy Corners: Fakes, Forgeries, and Questionable Origins

Speaking of stories, sometimes the story an artwork tells isn't just murky—it's completely fabricated. This moves us from unclear histories to outright deception. I've always found the idea of a forgery fascinating and deeply unsettling. Someone putting immense talent and effort into creating something designed to deceive. It's like spending hours perfectly replicating a classic recipe, only to pass it off as your own invention and claim it as your original dish. The skill is there, but the honesty is… well, conspicuously absent. Beyond the financial loss, buying a fake undermines trust in the entire art market. It devalues genuine works and disrespects the original artist's legacy. This isn't just about old masters; forgeries exist in every segment, even in the abstract market, sometimes even involving complex installations or historical documents. For instance, the infamous 'Hitler Diaries' forgery of the 1980s showed how even seemingly credible historical documents can be masterfully faked, shaking the foundations of historical research.

This is a constant battle, and one where collectors need to be armed with knowledge. This is where understanding provenance, the history of ownership, becomes a critical tool for authentication. Beyond expert opinions, the role of art conservators and technical analysis (like pigment testing, X-rays, or carbon dating) is increasingly crucial in authenticating artworks—think of them as forensic scientists for art, uncovering hidden truths. Organizations like the Art Loss Register also play a critical role, maintaining databases of stolen and questionable art to help prevent illicit trade. Reputable galleries and auction houses also play a vital role, investing heavily in due diligence to protect their own reputations and the trust of their clients. They have a responsibility to maintain high standards, follow ethical guidelines, and often police themselves to keep the market honest.

Beyond outright fakes, there's also the nuanced ethical gray area of art that's attributed to a famous artist but lacks definitive authentication. Terms like 'attributed to,' 'circle of,' or 'studio of' are used by reputable sellers when stylistic similarities or workshop practices suggest a connection, but conclusive proof is absent. It's crucial for collectors to understand that a piece merely 'attributed to' carries a significantly different historical and market value than a fully authenticated work by the master himself. Ethically, transparency is key: ensuring buyers are fully aware of the precise level of certainty—or uncertainty—surrounding an attribution, as this directly impacts both its cultural and financial significance. The ethical dilemma here isn't just financial; it's about whether you're comfortable presenting a piece as something it might not definitively be, and how that impacts trust in your collection. This also extends to artist's proofs or limited editions, where verifying the authenticity and authorized nature of the edition (e.g., ensuring no unauthorized editions exist, and that the edition number is accurate) becomes a specific ethical concern. Always verify the edition size and the artist's signature through expert channels. We've covered this extensively in A Collector's Guide to Identifying and Avoiding Art Forgeries in the Abstract Market.

So, how do you protect yourself? Due diligence, my friend. Get authentication from recognized experts. Be wary of deals that seem too good to be true—because they usually are. And remember, a good art advisor or gallery is your best ally. They have a reputation to uphold, which usually translates to integrity and a commitment to protecting their clients. Does the pursuit of beauty always come with a price tag of suspicion? How much scrutiny are you willing to apply to ensure the authenticity of your next acquisition, and how do you discern between honest attribution and speculative marketing?

Supporting the Creator, Not the Exploiter

Moving from the art's past to its present and future, we arrive at the artists themselves. As an artist, this one hits close to home. The struggle for artists to make a living, to gain recognition, and to simply keep creating is real. When you buy art, you have the power to directly support an artist's livelihood and their ability to continue their craft. It's a wonderful, direct connection that brings me immense joy when someone chooses one of my prints or paintings from my art for sale collection. It feels like a handshake across time and space.

But the ethical waters here can get a little murky too. Are artists being paid fairly? Is their work being appropriately credited? When an artwork enters the secondary market, especially if the artist is still alive and not seeing a cut of the resales, it raises questions. This is where concepts like artist resale rights—known as droit de suite in many European countries, including the Netherlands—become crucial. These rights ensure that artists, or their heirs, receive a percentage of the sale price each time their work is resold on the secondary market. For example, if an artist's painting sells for $10,000 today, and their resale right is 5%, they'd receive $500. It's a small but significant contribution that provides a crucial ongoing income stream, acknowledging that the value of their work can appreciate over time. While prevalent in Europe, these rights are not globally uniform; in the United States, for instance, there is no federal droit de suite, meaning artists often do not benefit from the increased value of their work on resale. As a collector, understanding and even advocating for artist resale rights, particularly in regions where they're not yet established, can be a powerful way to champion a more equitable art market. Your voice in supporting these policies can make a real difference for artists' long-term financial stability.

Beyond resale rights, fair compensation also involves transparent pricing and commission structures. Galleries typically take a commission (often 30-50%) from the sale of an artwork. An ethical gallery will ensure the artist understands and agrees to this, and that the pricing reflects a balance between the artist's livelihood, the gallery's operational costs, and market value. As a collector, don't hesitate to ask a gallery about their artist representation policies. Are they nurturing long-term careers, or are they purely transactional? This inquiry signals your care for the artist's well-being beyond the transaction. Moreover, collectors might occasionally encounter artists, especially emerging ones, who, due to lack of market experience, price their own work significantly below its true potential value. While a 'deal' might be tempting, an ethical collector might gently encourage the artist to seek fair guidance or ensure they're not inadvertently contributing to the undervaluing of artistic labor. Be wary of platforms that take excessively high commissions (sometimes 70% or more), as this significantly diminishes the artist's share and raises ethical questions about their commitment to supporting creators. We've explored the ins and outs of this in Navigating the Secondary Art Market.

For me, the most ethical way to collect, if you're looking to directly support creators, is to buy directly from the artist or from galleries that genuinely champion their artists. How do you spot them? Look for transparency in pricing, clear artist representation agreements, a history of consistent exhibition and promotion for their artists, and galleries that actively foster their artists' careers—perhaps by providing studio space, funding exhibitions, facilitating residencies, connecting them with mentorship opportunities, or actively promoting their work to critics and institutions—rather than simply acting as transactional intermediaries. Ask questions about how artists are compensated. Your purchase isn't just acquiring an object; it's an investment in a human being's passion and future. It's a quiet declaration that you value the creator as much as the creation. Are we truly valuing the hand that paints, or just the painting itself?

Moreover, artists themselves have a role to play in fostering an ethical market. By being transparent about their materials, production processes, and the original provenance of their work (if applicable), they empower collectors to make informed decisions and build trust.

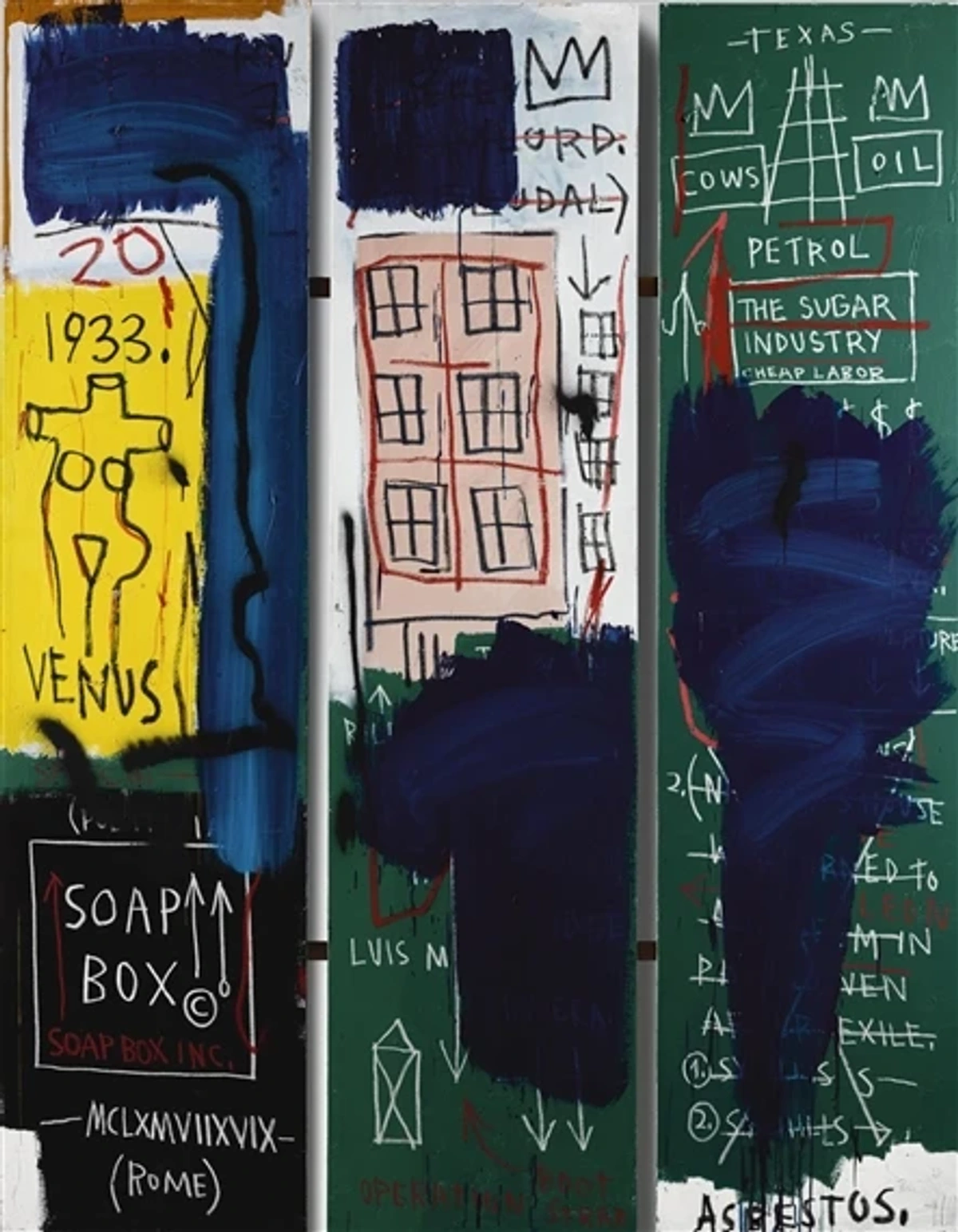

Art and Activism: Collecting with Purpose

Beyond just avoiding harm, ethical collecting can be a powerful force for good. Art has always been a vehicle for social commentary and change. As a collector, you have the opportunity to engage with and uplift artists who are using their voices to address pressing social, political, or environmental issues. This isn't just about passive appreciation; it's about making a deliberate statement. Imagine acquiring a piece that speaks to climate change, racial injustice, gender inequality, or indigenous rights—it transforms your collection into a platform. Collecting activist art isn't just about acquiring a piece; it's about making a statement, supporting a cause, and amplifying voices that need to be heard. It aligns your personal values with your collecting habits, turning your aesthetic appreciation into a purposeful act. This can mean seeking out artists from marginalized communities, supporting art that challenges the status quo, or investing in pieces that provoke difficult but necessary conversations. Think of artists like Ai Weiwei, whose work often critiques human rights abuses and political corruption, or the anonymous street artist Banksy, whose satirical pieces frequently address social and political issues. Even performance art collectives like Pussy Riot use their art for outspoken political activism. By supporting such artists, you're not just buying an artwork; you're actively participating in a dialogue, lending your support to vital social narratives, and helping to create a more just and aware world. For me, seeing an artwork spark a dialogue about a crucial issue is as powerful as the visual impact itself.

Navigating Nuance: Controversial Art and Ethical Boundaries

Sometimes the ethical questions aren't about provenance or authenticity, but about the art itself or the artist behind it. This brings us into the challenging territory of art that provokes discomfort. In today's hyper-connected world, it's increasingly likely that a living artist you admire might become embroiled in controversy, or their work might challenge societal norms in a way that feels uncomfortable. As a collector, this can be a tricky tightrope walk. What if an artist I bought from years ago, whose early work I loved, now makes public statements I find abhorrent? How does that change my relationship to the piece on my wall?

Do you stop supporting an artist whose past actions come to light, even if their art still deeply moves you? This touches upon the complex debate of "separating the art from the artist" – a philosophical stance where some argue the work stands independently, while others contend the creator's ethics are inseparable from their creation. Or do you engage with challenging art that some might find offensive, believing in its power to provoke thought and dialogue? There's no easy answer, and my own feelings on this shift depending on the specific context. It's a deeply personal ethical calculus. Imagine, for instance, an artist whose early work was groundbreaking and beautiful, but then later in life, they make public statements that contradict your deepest values. Do you still display their work? Or consider a piece that is visually striking but features imagery many find deeply unsettling—like the discussions around the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi exhibition of controversial artworks. Do you acquire it for its artistic merit and power to provoke discussion, or do you prioritize comfort and avoid potential conflict? This nuanced ethical calculus extends further to art that is politically charged or even promotes ideologies that some might find harmful. It also touches upon the concept of 'art washing,' where controversial figures or entities might use art acquisition and patronage to improve their public image, creating a moral dilemma for collectors inadvertently contributing to such narratives. Art washing is essentially the use of art to distract from or sanitize a problematic reputation, often by investing heavily in the arts to appear culturally progressive while simultaneously engaging in unethical practices elsewhere. For example, imagine a corporation with a poor environmental record heavily investing in a new art museum or sponsoring a major exhibition; a collector inadvertently participating could lend legitimacy to their 'greenwashing' efforts through association. Furthermore, ethical collecting also involves considering if the art itself has been created using ethically questionable materials or processes, such as the use of rare animal products, human remains, or potentially harmful chemicals without proper safety protocols or sustainable sourcing. Is there an ethical line at which art, despite its aesthetic or historical significance, becomes too problematic to acquire or display? This often involves weighing artistic freedom against social responsibility, and the potential for a piece to be interpreted as endorsement versus critique. The role of art critics and historians here is also crucial; they often provide essential context, historical perspectives, and interpretive frameworks that can help collectors navigate and understand challenging art without necessarily endorsing problematic elements. Your personal collection is, in many ways, a public statement – what message do you wish to convey when engaging with such challenging works? My advice? Be informed. Understand the nuances of the situation. Reflect on your own values and why you're drawn to the art. Sometimes, collecting controversial art can be a powerful statement in itself, sparking necessary conversations. Other times, it might cross a line that you, personally, aren't willing to traverse. This is where your personal conscience truly takes the lead, and it also requires you to be informed about the current actions and statements of living artists, not just historical controversies. How does your art reflect your values, and how do you navigate the discomfort of challenging truths?

Fair Exchange: Collecting from Emerging Markets & Vulnerable Cultures

These personal ethical calculations often lead us to consider broader questions of power and economics, particularly when engaging with art from diverse cultural contexts. When collecting from emerging economies or regions with less established art markets, an entirely different layer of ethical consideration comes into play. It's about ensuring a truly fair exchange. For me, this is about respect—respect for the artist, their community, and their cultural context. Are the artists being paid fairly, reflecting the true value of their work and effort, rather than being exploited by intermediaries taking disproportionate cuts?

This involves due diligence not just on provenance, but on the entire supply chain from creation to sale. Look for organizations and galleries that work directly with artists, provide transparent pricing, and ensure a significant portion of the sale price returns to the creator and their community. Transparent pricing, in this context, means a clear breakdown of where your money goes – how much goes directly to the artist, how much covers production costs, and how much is retained by intermediaries. When engaging with these vibrant markets, don't hesitate to ask critical questions: 'What percentage of this sale directly benefits the artist and their community?', 'What are the production costs, and are they fairly covered?', 'Are there local cultural protocols or sacred objects I should be aware of when considering this piece?' Look for cooperatives, artist-run initiatives, non-profit organizations focused on cultural preservation and fair trade, or established cultural foundations that support indigenous artists. These entities often have explicit missions to empower local artists, provide capacity building (which can involve workshops on business management, marketing, legal rights, or specific technical skills to help artists gain independence and thrive), and ensure that sales genuinely benefit the community, fostering sustainable development rather than dependency. It’s also crucial to understand and respect local cultural sensitivities, ensuring that culturally significant or sacred items are not commodified or acquired disrespectfully. This includes acknowledging that the local definition of 'fair exchange' might encompass not just monetary value, but also community benefits, cultural preservation, and long-term relationships, differing significantly from Western market expectations. For example, imagine finding a beautiful piece of textile art from a remote village. An ethical collector wouldn't just buy it from a roadside vendor; they'd seek out the collective that produced it, ask about their pricing structure, and understand its cultural significance to ensure the purchase truly empowers the community, not just a middleman. It’s about building relationships based on mutual respect, not just transactions. Additionally, be mindful of the potential for cultural appropriation—taking elements from a culture without understanding or respecting their original meaning, often by a dominant culture. Conversely, ethical engagement might mean commissioning an indigenous artist to create a piece that celebrates their culture, ensuring they control the narrative and benefit directly, rather than merely reinterpreting their motifs without understanding or permission. How can your collecting practices truly empower, rather than extract from, these vibrant communities?

The Digital Frontier: AI Art and New Dilemmas

Ah, AI art. My personal relationship with it is… complicated, like trying to explain a truly abstract painting to someone who only understands realism. It's fascinating, revolutionary, and yet, it brings a whole new set of ethical headaches. Who owns the copyright when an AI creates an image? Is it truly original, or just a sophisticated pastiche (a work that imitates the style of other works or artists, often incorporating elements from them) of countless human-made artworks it was trained on?

The training of AI models themselves raises significant ethical questions. Many AI art generators rely on vast datasets of existing images, often "scraped" from the internet without the explicit consent or compensation of the original artists. This data scraping creates a dilemma: are we inadvertently supporting technologies that exploit artists' styles and intellectual property without proper attribution or compensation? A particularly thorny issue arises when AI art generators are trained on vast datasets of copyrighted material without explicit consent or compensation of the original artists. My own internal debate flares up here: while the technical wizardry is undeniable, the thought that my abstract style, or that of my influences, could be 'fed' into a machine without my knowledge or compensation, and then used to generate competing art, feels profoundly unsettling. This raises serious questions about intellectual property rights and fair use. This directly brings up the concept of 'derivative works' under copyright law. Is an AI-generated image, trained on copyrighted material, a transformative derivative work that falls under fair use, or is it an infringing copy? My brain starts to ache just thinking about it, and honestly, it feels like trying to paint a coherent argument with a brush made of spaghetti. The answer is far from clear, and the legal battles are only just beginning. Beyond general style imitation, there's also the specific ethical concern of AI-generated work that closely mimics the distinct style of living artists without their consent or compensation, effectively creating a new form of digital appropriation that can directly compete with their livelihood. Even more complex is the ethical implication of AI art that attempts to mimic the distinct style of deceased artists. While copyright might have expired, the potential for misrepresentation, disrespect to their legacy, or a blurring of historical authenticity remains a significant concern for collectors and the art market. Even with prompt engineering – the careful crafting of text inputs to guide AI generation, like "create an abstract cityscape in the style of Kandinsky with neon lights and rain effects" – the underlying ethical questions of data sourcing remain. As a collector, if you're venturing into AI art, look for platforms or artists who are transparent about their training data sources and actively engage in ethical sourcing practices, perhaps even contributing to compensation models for artists whose work informs the AI. Beyond attribution and compensation, there's also the emerging concern of AI-generated deepfakes and misinformation in the art world – images or even 'artist statements' that could deceive collectors about an artwork's true origin or meaning, eroding trust and authenticity. How do we ensure the digital art landscape remains authentic and transparent, rather than becoming a breeding ground for sophisticated artistic deceptions? I've often found myself wondering if embracing AI-generated work, despite its allure, might inadvertently diminish the value of the unique human touch in my own abstract creations. It’s an internal debate I grapple with.

However, it's not all trepidation; AI also holds potential for positive ethical applications, such as assisting in art conservation through advanced imaging, helping to authenticate works via complex pattern recognition, or even aiding in provenance research by sifting through vast historical archives. It's a brave new world, and honestly, the rules are still being written. As a collector, you might encounter AI-generated art that truly captivates you. But the ethical questions are profound. Are we unintentionally devaluing human creativity by embracing AI art without clear guidelines? Or could AI also be a powerful tool assisting artists, expanding their creative horizons rather than replacing them? If you're delving into this brave new world, I highly recommend two of our articles: Understanding the AI Art Market: Trends, Opportunities, and Ethical Considerations for Collectors and The Ethics of AI Art: Copyright, Authenticity, and the Future of Creativity. They're essential reading for any forward-thinking collector. Where do we draw the line between tool and creator, and how will your collection define that boundary?

My personal take? AI is a tool, and like any tool, its ethical implications depend entirely on how we wield it. For now, I'm sticking to my own two hands and a brush, but I'm watching this space with a mix of awe and trepidation.

Art and Accessibility: Breaking Down Barriers

While we focus on the ethics of acquisition, it’s also vital to consider the broader accessibility of art as a collective responsibility. The art world, with its exclusive auctions and soaring prices, can often feel impenetrable. This raises ethical questions about who gets to experience, own, and even create art. When art becomes solely a commodity for the ultra-wealthy, it risks alienating the very public it's meant to inspire. It’s a paradox: I want my art to be valued, but I also believe its magic shouldn't be locked away behind gilded ropes. My own museum in Den Bosch museum aims to be a welcoming space, but beyond that, what can collectors do? Ethical collecting can also mean advocating for broader access to art, supporting initiatives that democratize art appreciation, and considering how your own collection can contribute to this goal. This might involve supporting public art commissions, sponsoring free museum days, donating to art education charities that run workshops in underserved communities, or advocating for art therapy programs that reach those who might otherwise be excluded from art's benefits. It's about recognizing art's role as a public good and fostering an environment where its transformative power is available to all.

Beyond the Canvas: Environmental Footprint & Responsible Care

As we navigate the digital frontiers of art, it's also crucial to remember the tangible impact of our collecting habits on the physical world. Collecting art, in many ways, is a reflection of yourself. What you choose to bring into your home, how you acquire it, and the stories behind it all speak volumes. For me, it's about building a collection that I can look at every day, not just with aesthetic pleasure, but with a clear conscience. Sometimes, this means saying no to a piece, no matter how much I love it, if its history is tainted.

The Environmental Footprint of Art

Ethical collecting stretches even further than provenance and creator rights. Have you ever considered the environmental impact of the art market? When I'm in my studio, surrounded by paint fumes and half-used tubes, I often think about the lifecycle of my materials. It's not just about what goes into the art, but what happens around it. From the materials used in creating art (paints, canvases, sculpting materials) to the energy consumption of galleries and museums, the carbon footprint of shipping artworks across continents, and even the waste generated by art fairs and exhibitions – it all adds up. Responsible collecting might involve embracing actions that empower a healthier planet:

- Considering sustainable materials: Prioritizing artists who use eco-friendly paints, recycled canvases, or natural pigments like earth ochres or bio-based paints. Ask about the artist's studio practices regarding waste management, energy sources, and material sourcing. Supporting artists who integrate sustainable practices, like reclaiming materials or employing zero-waste techniques, contributes to a healthier planet.

- Minimizing transport: Opting for local artists or less frequent, more efficient shipping methods. Could you consolidate purchases or support virtual viewings? Choosing local reduces carbon emissions and supports your immediate artistic community.

- Reducing waste: Supporting galleries that implement green practices, like minimizing single-use materials for packaging, using renewable energy, or responsible disposal. This includes everything from sustainable exhibition design to the ethical disposal of unsold or damaged artworks.

- Framing and display choices: Selecting sustainably sourced woods for frames (look for certifications like FSC) or archival, acid-free materials that prolong the life of the artwork, reducing the need for replacements and future waste. High-quality, durable framing is an investment in both your art and the planet. Also, consider the long-term energy consumption of art storage, especially for collections requiring climate control; optimizing these systems can significantly reduce the environmental footprint.

- Responsible disposal of art materials: Properly disposing of art chemicals and materials, recycling old frames, or donating usable supplies to art schools are small but impactful actions.

It’s a bit like deciding what kind of food you want to eat: you can grab something cheap and fast, or you can seek out ethically sourced, sustainably produced ingredients. Both fill you up, but one leaves a much better taste in your mouth, and a clearer conscience. The same applies to art. Be curious, be critical, and trust your gut. If something feels off, it probably is. Does your collection contribute to a sustainable future, or is its footprint a hidden cost? For a deeper dive, read The Definitive Guide to Sustainable Art Collecting: Ethical Choices for the Conscious Buyer.

The Ethics of Art Conservation and Restoration

A new layer of ethical consideration emerges when we think about preserving art. Conservation focuses on stabilizing an artwork to prevent further deterioration, while restoration aims to return it to a perceived earlier state, often involving more invasive procedures. When a piece undergoes either, who decides how much to alter it? Is it ethical to restore a piece in a way that significantly changes its original appearance or materials, even if it ensures its survival? Or should the focus always be on minimal intervention, preserving the artist's original intent, even if it means acknowledging damage or deterioration? This balance between preservation and alteration requires careful consideration and consultation with experts. As a collector, before entrusting a piece to conservation or restoration, always inquire about the conservator's philosophy and approach, specifically regarding their stance on minimal intervention versus reintegration of missing parts, and insist on detailed documentation of the original state of the artwork before any intervention, alongside visual and written records of the entire process. This due diligence ensures your cherished piece is treated with the utmost respect for its history and the artist's original intent. It’s about being a thoughtful custodian of culture, a supporter of artists, and a responsible participant in a beautiful, complex world.

Art as Investment vs. Art as Appreciation: A Delicate Balance

This is where the heart meets the ledger, isn't it? The thrill of an acquisition can sometimes blur the line between passion and profit. For me, the true value of a piece is never just its market price, but the story it tells and the integrity of its journey. But an ethical question arises when the pursuit of financial gain overshadows the appreciation of art and its creator. Speculation in the art market, where pieces are bought and sold rapidly to turn a profit, can drive up prices artificially, making art less accessible to new collectors, institutions, and even the artists themselves. It can also incentivize the production of art for commercial trends rather than genuine artistic expression. Ethically, a collector might ask: am I supporting the art market as a sustainable ecosystem for artists, or am I primarily contributing to its speculative tendencies? The goal isn't to demonize art as an asset, but to encourage a mindful approach where financial decisions are balanced with cultural responsibility and a genuine love for the art itself. Consider setting a personal 'ethical acquisition budget' for your art purchases, ensuring a portion is dedicated to supporting emerging artists, marginalized communities, or art forms aligned with your values, rather than solely focusing on potential appreciation. It's a way to consciously steer your influence towards a more vibrant and equitable art ecosystem.

A related ethical dilemma in the institutional world is deaccessioning: the process by which a museum formally removes an item from its collection, often for sale. Ethical deaccessioning requires clear policies, transparency, and often involves using the proceeds solely for new acquisitions or the direct care of existing collections, avoiding sales purely for operational costs. Individual collectors can look to these institutional best practices as a guide for their own stewardship. Indeed, the ethical responsibilities of museums and galleries in provenance research, fair artist compensation, and transparent operations serve as crucial benchmarks for private collectors, who might even consider drafting their own 'collection policies' to formalize their ethical commitments and guiding principles.

Furthermore, a truly responsible collector commits to continuous learning. Consider joining professional art organizations with ethical guidelines, attending lectures on art law and provenance, or subscribing to reputable industry publications. This ongoing education is an investment in your own ethical framework, constantly refining your understanding of this evolving landscape. And don't forget the practical side: understanding art insurance is also crucial. While primarily financial protection, it underpins ethical collecting by necessitating accurate valuations, which in turn demands thorough provenance checks. A piece with dubious origins might be uninsurable or valued differently, pushing collectors towards greater due diligence and transparency.

If you ever find yourself in 's-Hertogenbosch, feel free to visit my Den Bosch museum and see some of the pieces that tell my own story, each with its own clear, ethical provenance.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ethical Art Collecting

Here are some common questions I hear, or sometimes ask myself, on this fascinating and sometimes challenging journey of ethical art collecting. Think of this as a shared common ground for navigating these important waters:

Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is provenance, and why is it so important? | Provenance is the history of ownership of a work of art. It's crucial because it establishes the artwork's authenticity, can verify its legal ownership, and helps identify if it has been illegally acquired (e.g., looted during wartime, illegally excavated, or stolen from private collections without documentation). |

| How can I research an artwork's history or provenance? | Start by asking the seller for all available documentation. This can include bills of sale, exhibition catalogs, scholarly publications, and prior ownership records. Independent art historians, auction houses, and specialized research services (like the Art Loss Register) can also help. For cultural heritage pieces, consult databases of stolen or illicitly traded art. |

| What are red flags for unethical art or questionable provenance? | Lack of detailed provenance, vague seller information, prices significantly below market value, a sense of urgency that feels less like enthusiasm and more like manipulation to buy quickly, or refusal to provide authentication or allow independent examination are all major red flags. |

| How should I approach a seller if I suspect questionable provenance? | Politely and professionally express your concerns, requesting additional documentation or clarification. Frame it as a necessary part of your due diligence. If they become defensive, refuse to provide more information, or pressure you, it strongly indicates you should walk away. |

| Is it always wrong to buy art without clear, complete provenance? | Not necessarily, especially for contemporary art where the artist is the original source. However, for older, culturally significant pieces, or pieces with a history of ownership through private collections, incomplete provenance is a significant risk. Always proceed with extreme caution and expert advice. |

| How can I ensure I'm supporting artists ethically? | Buy directly from artists, or from reputable galleries that have clear, fair contracts with their artists. Research the gallery's reputation and ask about their artist compensation practices, specifically avoiding platforms with excessively high commissions. Consider buying from artist-run initiatives or non-profit organizations that support artists. |

| What is the role of an art advisor in ethical collecting? | A good art advisor acts as a trusted guide, conducting due diligence on provenance, authenticity, and fair pricing. They can help navigate complex ethical dilemmas, connect you with reputable dealers, and ensure your collection aligns with your values. |

| What should I do if I discover a piece I own has questionable provenance? | This can be a challenging situation, potentially fraught with legal ramifications. First, seek expert legal counsel specializing in art law, alongside art historical advice. Depending on the specifics, you may need to cooperate with authorities, consider restitution to the rightful owners, or work with specialists to clarify its history. Document everything meticulously. |

| How does art insurance relate to ethical collecting? | While primarily financial protection, ethical art insurance requires accurate valuation, which can be difficult with questionable provenance. It also encourages transparent declaration of an artwork's history, as undisclosed issues could impact coverage. |

| What are the ethical considerations when collecting art from living cultural heritage? | When collecting art from a living culture, it's absolutely paramount to engage respectfully and directly with the community and its artists. This involves understanding whether the art holds sacred significance, actively ensuring artists are fairly compensated according to local standards, diligently avoiding cultural appropriation, and deeply respecting traditional ownership and intellectual property rights. Always prioritize direct engagement with the artists or community-led initiatives, and seek guidance from cultural elders and experts. The ultimate goal is to genuinely support and sustain the culture, empowering its creators, rather than inadvertently exploiting or commodifying their heritage. |

| How can I ethically support emerging artists? | Seek out local art fairs, artist studio visits, and online platforms dedicated to emerging talent. Purchase directly from the artist or from galleries known for fair artist contracts. Consider mentoring or offering practical support where appropriate, and always ensure fair compensation that reflects their labor and creative value, even if they are new to the market. Also, consider setting aside an 'ethical acquisition budget' specifically for this purpose. |

| What are the ethical implications of 'flipping' art? | 'Flipping'—buying art with the sole intention of quickly reselling it for a profit—can drive up prices, making art less accessible, and can destabilize an artist's nascent market. While not inherently unethical, it can be problematic if it exploits artists or market trends without contributing to the art ecosystem's long-term health or the artist's career development. Consider the artist's intentions and the impact on their market. |

| Is it ethical to buy directly from an artist, and how should I do it? | Absolutely! Buying directly from an artist is one of the most ethical ways to support their practice, as they receive 100% of the sale. Approach them respectfully, admire their work, and inquire about their pricing. Don't aggressively haggle, as this undervalues their labor. Be clear about your interest and intentions, and establish a polite, professional connection. |

| What are the ethical considerations for AI-generated art? | Key concerns include copyright ownership (who owns the AI-generated image?), the ethics of data scraping (training AI on copyrighted works without consent or compensation), and the potential for AI to mimic living or deceased artists' styles, impacting their livelihood or legacy. Transparency about training data and ethical compensation models are crucial. |

| How can collectors contribute to art accessibility? | Beyond buying, collectors can support art education charities, sponsor local community art workshops, lend works to public institutions, advocate for public art programs, and ensure their own collecting practices don't contribute to market speculation that makes art inaccessible. |

| What are the ethical implications of collecting art from artists accused of plagiarism or intellectual property theft? | Collecting art from artists accused of plagiarism or IP theft raises significant ethical concerns. It can indirectly legitimize the alleged theft, disrespect the original creator, and undermine the integrity of the art market. It's crucial to research such claims thoroughly, understand the artist's response, and consider the potential impact on your collection's ethical standing and your personal values before acquiring such work. |

It’s a beautiful thing to surround yourself with art. But it’s an even more beautiful thing to do so knowing you’ve collected with integrity, thoughtfulness, and respect for the stories—both seen and unseen—within each piece. Despite the complexities, there's an immense joy in collecting ethically – a quiet satisfaction in knowing that each piece not only brings beauty into your life but also tells a story of respect, integrity, and support for the human spirit that creates it. And honestly, there's a particular kind of quiet joy in it—a deeper resonance that goes beyond just aesthetics, knowing you're building a collection that truly gives back, piece by thoughtful piece. The journey of collecting ethically is continuous, just like the ongoing conversation within the art world itself. Embrace it, engage with it, and share your own discoveries. What stories does your collection tell about you, what legacy do you hope it leaves, and how will you continue to champion integrity in the art world?