Collecting Drawings & Sketches: A Personal Window into the Artist's Soul

Collecting drawings and sketches offers a unique, intimate window into an artist's mind and process. Discover why these often-overlooked pieces are perfect for starting or expanding your art collection, from an artist's personal perspective, covering types, media, techniques, care, finding pieces, and more.

Collecting Drawings & Sketches: A Personal Window into the Artist's Soul

Let's talk about something a little different today. We often think of collecting art in terms of grand paintings or imposing sculptures. But there's a whole world of intimacy and raw creativity waiting in the realm of drawings and sketches. For me, as an artist, these pieces hold a special kind of magic. They're not always the polished, finished product, and that's precisely their charm. It's like catching an artist mid-thought, pencil in hand, before the grand performance begins. Plus, they're often more accessible price-wise than paintings, making them a fantastic entry point into collecting. If you're thinking about starting an art collection on a budget or just want to connect with art on a deeper level, this is a fantastic place to start.

Collecting drawings and sketches feels like getting a backstage pass to the creative process. It's seeing the artist's hand, their initial thoughts, their struggles, and their breakthroughs, often captured in a moment of pure, uninhibited flow. I remember the first time I held a small, quick sketch by an artist I admired – it wasn't famous, just a few lines on paper, but it felt electric, like a direct line to their creative energy. That feeling is what collecting drawings is all about.

The Artist's Soul on Paper: Why Drawings Feel So Intimate

Why do drawings feel so much like a direct line to the artist's soul? It's about vulnerability and immediacy. Unlike a painting, which can be built up in layers, reworked, and polished over time, a drawing often captures a moment in its rawest form. Every line, every smudge, every hesitant mark is visible. There's nowhere to hide. It's the artistic equivalent of thinking out loud, and as a collector, you're privy to that unfiltered thought process. It's seeing the artist's hand literally moving across the page, making decisions in real-time. It's a level of intimacy that's hard to find in other art forms. I look at some of my own early sketches, and I can instantly recall the feeling, the struggle, the idea I was chasing in that exact moment. It's like a time capsule of creative energy.

The Act of Drawing: More Than Just a Tool

Before we dive deeper into collecting, it's worth pausing to appreciate just how fundamental drawing is, not just as a tool for other art forms, but as a complete act in itself. For me, drawing isn't just a step towards a painting; it's a fundamental way of thinking and seeing. It's the most direct connection between my mind, my hand, and the surface. There's a vulnerability in that directness. Every wobble, every hesitant line, every confident sweep is recorded. When you collect a drawing, you're collecting that raw, immediate thought process. It's a practice that requires intense focus, observation, and a willingness to make mistakes visible. It's the artistic equivalent of thinking out loud. Seeing how other artists think out loud on paper is endlessly fascinating and inspiring.

Sometimes, I'll do a quick blind contour drawing, where I don't look at the paper, just the subject, letting my hand wander – it feels like pure observation translated directly onto the page, capturing the essence rather than the perfect form. Or a series of rapid gesture drawings, trying to capture movement in seconds. These exercises strip away the polish and reveal the core act of seeing and responding. And seeing that raw response in another artist's work? That's the magic.

Drawing's Enduring Role in Art History

Drawing is the backbone of so much art, and understanding its history adds another layer of appreciation for the drawings you collect. It wasn't always seen as a standalone art form; for centuries, drawing was the foundation of artistic training and creation. In Renaissance workshops, apprentices spent years honing their skills through drawing, copying masters, and studying anatomy. These preparatory drawings were essential steps towards creating frescoes, sculptures, and paintings. Academic art training, which dominated for centuries, was heavily centered around life drawing and mastering form through line and tone.

Historically, the tools themselves tell a story. Before graphite pencils became common, artists used silverpoint, which leaves a delicate line that oxidizes over time, or natural chalks (like red sanguine, black, and white) and simple charcoal sticks made from burnt wood. These media each have their own character and limitations, influencing the artist's mark-making. Imagine the feel of a rough charcoal stick dragging across textured paper, or the subtle precision required for silverpoint on a specially prepared surface. Collecting drawings from different periods allows you to connect with these historical materials and techniques directly.

As art evolved, drawing remained a crucial tool for planning, experimenting, and capturing ideas. However, its status began to shift, particularly in the 19th century, with artists like Ingres elevating the finished drawing to a primary art form. In the 20th and 21st centuries, drawing has exploded as a versatile and powerful medium in its own right, used for everything from conceptual pieces to monumental installations. Collecting drawings is celebrating this long, rich tradition and its ongoing evolution.

Consider Albrecht Dürer, whose meticulous preparatory drawings and studies for his famous engravings and woodcuts are masterpieces in themselves, revealing an incredible eye for detail and form. Or the Surrealists, who used drawing techniques like automatism – drawing without conscious thought – as a way to tap into the subconscious mind, creating raw, often bizarre, and deeply personal images. Even in non-Western traditions, drawing has played a vital role, from the intricate ink brushwork in East Asian painting to the detailed preparatory sketches for murals and sculptures in various cultures. Understanding this rich history deepens the appreciation for the simple act of putting line to paper.

Why Drawings & Sketches Deserve Your Attention

Drawings and sketches are far more than just preliminary studies (though they are often that, too!). They are complete works in themselves, offering unique insights into the artist's mind and process.

The Artist's Hand: Raw and Immediate

There's an immediacy to a drawing that you don't always find in a painting. The line, the pressure of the pencil or charcoal, the quick wash of ink – it's all right there, unfiltered. You can almost feel the artist's energy and intention in that moment. It's a direct conversation between the artist and the surface. Think about the raw energy in an Egon Schiele drawing, where every line feels charged with emotion, revealing the artist's inner turmoil and intensity. Or the delicate precision in a preparatory sketch by Leonardo da Vinci, like his anatomical studies, revealing the meticulous thought and deep understanding behind the masterpiece. It's the visible trace of a mind at work. I have a small, almost abstract sketch by a contemporary artist I follow; it's just a few bold, sweeping lines, but looking at it, I can almost feel the speed and confidence of their hand moving across the paper. It's a jolt of creative energy every time I see it. It feels like a direct connection to the artist's soul.

A Window into the Creative Process

Collecting sketches is like owning a piece of the artist's journey. You see how an idea evolved, how they worked through a problem, or how they captured a fleeting impression. It's a peek behind the curtain, revealing the thought process that leads to a finished piece. This can be incredibly insightful, especially if you're interested in how artists use color or composition basics. I often find myself drawn to sketches that show the artist figuring things out, maybe a hand study that didn't quite work, or a quick compositional thumbnail. It reminds me that art isn't just magic; it's work, exploration, and sometimes, happy accidents. I have sketchbooks filled with ideas that went nowhere, quick studies for paintings that changed completely, and just random doodles. Seeing a finished drawing that started as a tiny, messy thumbnail sketch is incredibly rewarding. A quick sketch can capture a fleeting expression or movement that might be lost in a longer, more deliberate painting process. Preparatory studies, in particular, offer a tangible record of an artist's problem-solving – you can see them working out anatomy, perspective, or compositional balance line by line. It's a privilege to witness that process. Consider Leonardo da Vinci's detailed studies for the figure of St. Anne in The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist, where you can trace his exploration of pose and drapery before the final painting. Sometimes, you can even see pentimenti – visible traces of earlier, altered forms or lines beneath the final drawing – like ghosts of decisions made and changed. These aren't flaws; they're physical evidence of the artist's mind at work, a visible history of the creative struggle and evolution.

Often More Accessible (Price-wise)

Let's be honest, understanding art prices can be daunting, and original paintings can be expensive. Drawings and sketches, however, are often significantly more affordable. This is partly because they can be less time-intensive to create than a large painting, and the materials (paper, pencil, ink) are generally less costly than canvas and oil paints. This makes them an excellent entry point for new collectors or a way to acquire work from established artists you might not otherwise be able to afford. It's a smart way to buy art for less without compromising on authenticity or connection. You might find a stunning, original drawing by an artist whose paintings are out of reach, allowing you to still own a piece of their unique vision. It's a way to start building a meaningful collection without needing a massive budget.

The Purpose of Collecting Drawings: Beyond Investment

Beyond the practicalities of accessibility and the intellectual insight into process, why collect drawings? For many, it's a deeply personal pursuit. It's about the joy of discovery – finding a hidden gem in a portfolio or connecting with an artist's early work. It's about the connection to history, holding a piece of paper that bears witness to centuries of artistic practice. It's about the unique aesthetic pleasure of line, form, and tone on paper, a different visual language than paint or sculpture. And crucially, it's about the opportunity to support living artists, acquiring work directly from them and becoming a patron of contemporary creativity. It's less about the potential for financial return (though that can happen) and more about building a collection that resonates with your soul and tells a story about your journey with art.

Different Drawing Media, Techniques, and Types

Not all drawings are created equal, and understanding the different media, techniques, and types can enrich your collecting experience. It's like learning the language the artist is speaking.

Drawing Media: The Artist's Tools

The material the artist uses is the starting point. The feel of the medium on the paper, the way it responds to pressure, the depth of tone it can achieve – these are all part of the artist's language, and the collector's sensory experience. The sound of a graphite pencil scratching across paper, the dusty feel of charcoal, the decisive glide of an ink pen – these physical sensations are embedded in the final image.

- Pencil: Versatile, from delicate lines to deep shading. Graphite pencil is common, available in a range of hardnesses (from hard 'H' grades for fine lines to soft 'B' grades for rich blacks). Silverpoint offers a unique, subtle line that tarnishes over time, requiring a specially prepared surface. Think of the precision in a Renaissance portrait study using silverpoint.

- Charcoal: Expressive and dramatic, allowing for rich blacks and soft tones. Available as vine charcoal (soft, easily smudged) or compressed charcoal (harder, darker). Can be messy, which adds to its raw appeal. Requires fixative to prevent smudging. Working with charcoal feels like wrestling with smoke and dust, but the depth you can achieve is incredible. Egon Schiele's intense figure studies often utilize charcoal's expressive power.

- Ink: Offers permanence and bold lines, whether applied with a pen or brush. Think of the fluid lines of Japanese sumi-e or the graphic punch of a comic book sketch. Can range from delicate washes to strong, defined strokes. Ink is decisive; there's no going back, which forces a certain kind of confidence. Historically, media like reed pen and quill pen were fundamental, each leaving its own distinct mark. Rembrandt's expressive ink sketches are legendary.

- Pastel & Conté Crayon: Pigment sticks that offer vibrant color and painterly effects, blurring the line between drawing and painting. They sit on the surface of the paper and require careful handling and framing. Pastels feel like drawing with pure color, almost like sculpting light. Sanguine crayon, a reddish-brown pigment, is another beautiful historical medium often used for figure studies, notably by artists like Antoine Watteau.

- Colored Pencils: Offer a wide spectrum of color with varying degrees of opacity and blendability, allowing for detailed, layered color work. Contemporary artists like Kristy Mitchell use colored pencils to achieve incredible detail and richness.

Drawing Techniques: How the Marks are Made

Beyond the medium, the way the artist applies it creates the final image. Understanding these techniques helps you appreciate the skill and intention behind the marks and how they build form, texture, and tone:

- Line Drawing: Focusing purely on contour and outline, often with minimal shading. Emphasizes form and structure. Think of the elegant simplicity in a Matisse line drawing.

- Hatching and Cross-Hatching: Building up tone and shadow through parallel lines (hatching) or intersecting sets of parallel lines (cross-hatching). The density and direction of the lines create form and texture. It's like weaving with lines to create shade. Albrecht Dürer was a master of cross-hatching in his preparatory drawings for engravings.

- Stippling: Creating tone and texture using dots. Denser dots create darker areas, while sparser dots create lighter areas. Requires immense patience! (Seriously, my hand cramps just thinking about it.)

- Scribbling/Circulism: Using random or circular marks to build tone and texture. Can create a sense of energy and spontaneity.

- Blending/Smudging: Using fingers, a tortillon, or cloth to smooth out charcoal, pastel, or pencil marks, creating soft transitions and tones. This technique can create a sense of atmosphere or softness.

- Wash: Applying diluted ink or watercolor with a brush to create tonal areas or atmospheric effects. Often used in combination with line work. Many traditional East Asian ink painters utilize wash techniques beautifully.

- Grisaille: Creating a drawing or painting using only shades of gray or a single color (like sepia or sanguine) to mimic sculpture or create a monochromatic effect.

Types of Drawings: Purpose and Finish

It's helpful to distinguish between 'sketch' and 'drawing' for collecting purposes, though the lines can be blurry. Think of it as a spectrum. A sketch often implies a quick, spontaneous capture of an idea, observation, or movement, typically less finished. These are often smaller in scale, capturing a fleeting moment. Common subjects include quick figure studies, landscape observations, or still life arrangements, capturing the artist's immediate response to the visual world. A drawing can be a sketch, but it can also be a more developed, finished work intended as a standalone piece, which might be larger and more detailed. The artist's intent and the level of finish are key.

- Gesture Drawings: Quick, energetic studies capturing movement and form, often done in minutes. They are pure immediacy, focusing on the essence rather than detail. You can often tell by the loose, sweeping lines. Think of quick life drawing poses. Typically small scale.

- Preparatory Studies / Working Drawings: More detailed drawings used to plan larger works, like paintings or sculptures. These offer deep insight into the artist's process and decision-making. Look for detailed anatomical studies, compositional layouts, or studies of specific elements within a larger planned work. Unlike finished drawings, their primary purpose was functional, a step towards a larger goal, though they often possess immense artistic merit in their own right. Leonardo da Vinci's studies are classic examples. Scale varies depending on the detail needed. Working drawings are specifically those used by the artist during the creation process, often showing changes and explorations. Sometimes, these include artist's notes, annotations, or small color studies in the margins, offering unique insights into their thinking.

- Finished Drawings / Presentation Drawings: Works intended as complete pieces in themselves, often highly detailed and refined. The artist's intent is key here; they are presented as standalone artworks, not just steps towards something else. These are often signed and dated, treated with the same consideration as a painting. Presentation drawings are finished works often made for a client or patron, intended to showcase the final concept. Scale can range from small to monumental.

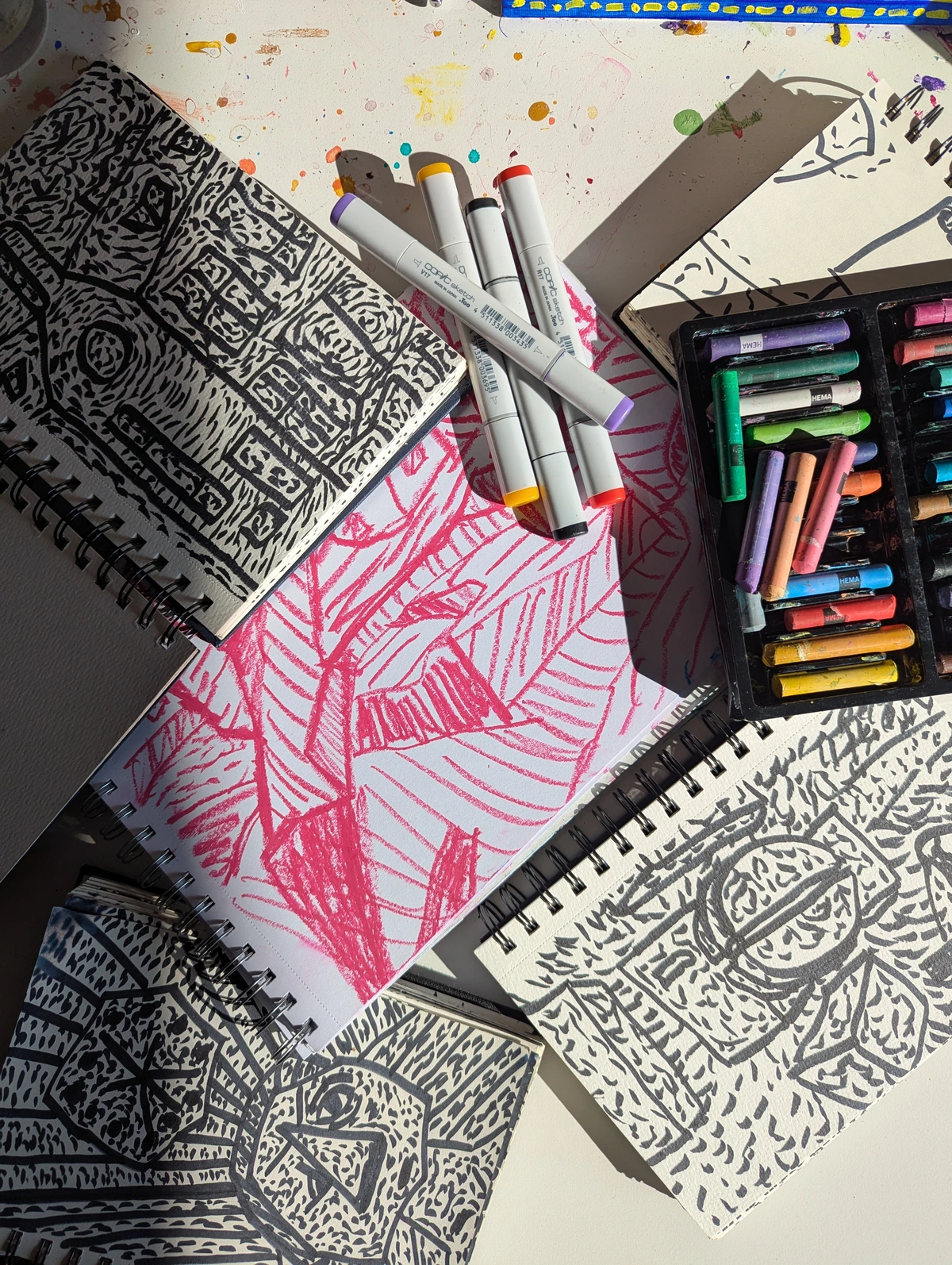

- Sketchbook Pages & Life Sketches: Individual pages or even entire sketchbooks offer the most intimate view, capturing fleeting ideas, observations, and experiments. These can range from quick doodles to more developed studies. Sketches made directly from life, capturing a moment or observation, fall into this category and offer a raw, unfiltered perspective. As an artist, my sketchbooks are a chaotic mix of all of these – a true window into my messy, evolving thoughts! Collecting entire sketchbooks or facsimiles can offer a unique chronological insight into an artist's development. Scale is usually small, limited by the sketchbook size.

- Mixed Media Drawings: Drawings that incorporate other materials like paint, collage, or pastels alongside traditional drawing media, blurring the lines between disciplines. Scale varies widely.

Understanding these nuances helps you appreciate the artist's choices and the unique character of each piece. It also gives you clues about how to properly care for them and can even inform your understanding of the artist's broader practice. For instance, seeing an artist's confident ink sketches might give you insight into the decisive brushstrokes in their paintings. It's all part of the visual language.

The Importance of Paper: More Than Just a Surface

Just as important as the medium and technique is the surface it's applied to. The type of paper used can significantly impact the look, feel, and longevity of a drawing. Different papers have different textures (tooth, which refers to the surface texture or grain), weights, and compositions. The tooth of the paper can dramatically affect how the medium sits and interacts with the surface – a rougher tooth grabs charcoal beautifully, allowing for rich textures, while a smooth surface is necessary for the fine lines of a silverpoint drawing. As an artist, choosing the right paper feels like finding the perfect dance partner for the medium; the texture and weight influence every mark I make.

Common paper types for drawing include:

- Newsprint: Inexpensive, thin, and acidic. Often used for quick sketches or studies, especially gesture drawing. Not suitable for archival purposes as it yellows and becomes brittle quickly.

- Sketch Paper: Lighter weight, general-purpose paper suitable for practice and quick studies. Quality varies.

- Drawing Paper: Heavier weight than sketch paper, with more tooth. Suitable for finished drawings in pencil, charcoal, or pastel.

- Bristol Board: Smooth, plate-like surface (hot-press) or slightly textured surface (cold-press). Excellent for ink, marker, and fine detail pencil work. Comes in various plies (thicknesses).

- Watercolor Paper: Heavy and textured (cold-press or rough) or smooth (hot-press). Designed to handle wet media like ink washes without buckling. The texture can add interesting effects to dry media as well.

- Laid Paper: Features a distinctive ribbed texture created during manufacturing, adding a unique visual element and historical feel. Often used historically.

- Wove Paper: In contrast to laid paper, has a smooth, uniform surface.

Other historical surfaces include vellum (prepared animal skin, offering a smooth, durable surface) or even prepared panels (wood or other rigid supports coated with a ground). While less common for collecting today, encountering drawings on these surfaces adds another layer to art history.

The quality of the paper is also crucial for preservation; acid-free or archival paper is essential to prevent yellowing, brittleness, and deterioration over time. Acidic paper, common in older sketchbooks or newsprint, will degrade significantly faster. When collecting, understanding the paper helps you appreciate the artist's material choices and ensures you know how to store and frame the work correctly. The feel of a thick, textured paper under a charcoal stick is completely different from the smooth glide of a fine pen on Bristol board – these material choices are part of the artwork itself. It's a tactile element that adds to the experience. And honestly, the smell of old paper and ink can be intoxicating – it's the scent of history and creativity combined.

What to Look for When Collecting Drawings

So, you're intrigued. You understand the 'why' and the 'what'. Now, what should you keep in mind when you start looking? It's a bit like detective work, mixed with falling in love.

The 'Spark' and Personal Connection

Just like any art, the most important thing is that it speaks to you. Does the drawing capture something, evoke a feeling, or resonate with your personal art style and taste? Don't just buy because you think it should be valuable; buy because you love it. That personal connection is priceless. I remember seeing a small, quick sketch by an artist I admire – it wasn't their most famous work, but the energy in the lines perfectly captured a feeling I understood. That's the spark. It's the piece you keep coming back to, the one that feels like it was made just for you. Trust your gut; if a drawing makes you pause, look closer, and feel something, that's a strong sign.

Authenticity, Provenance, and Artist Marks

Knowing the history of the piece – its provenance – is important. Where did it come from? Was it acquired directly from the artist, a gallery, or a reputable collector? This helps establish authenticity. When researching artists, especially emerging artists worth collecting, ask questions! Don't be shy; it's part of the process. Does the drawing fit within the artist's known drawing style and period? Look for artist signatures, monograms, dates, titles, or even studio stamps – these can be key indicators of authenticity. For contemporary works, a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) is common practice and provides crucial documentation. Familiarizing yourself with an artist's typical approach to drawing can be a valuable tool. Researching the artist's specific drawing practice – whether it was a core part of their work or just occasional – can also add context and help verify authenticity. Artists sign drawings in various ways, and understanding these can be helpful. Some sign prominently on the front, others subtly in a corner, or only on the back. These marks can vary depending on the artist's period or even the purpose of the drawing (a quick sketch might be unsigned, while a finished drawing is often signed). Knowing an artist's typical signing habits adds another layer to the authenticity check. Also, look for evidence of the artist's process itself – faint under-drawing, corrections, or even smudges that seem intentional can be further clues to the artist's hand and the drawing's authenticity.

Quality and Condition

Paper is delicate. Look for drawings on good quality paper that hasn't yellowed excessively or shown signs of foxing (those little brown spots caused by mold or impurities). The medium (pencil, ink, charcoal, pastel) should be well-preserved. Condition is key for long-term value and enjoyment. This ties into how to take care of your art in general. Always handle works on paper with clean, dry hands, or ideally, wear cotton gloves. I once saw a beautiful drawing ruined by careless handling – it was a stark reminder of how fragile these pieces are. And honestly, the thought of a coffee stain near a beloved piece on paper gives me mild anxiety! When buying from a gallery or auction house, don't hesitate to ask for a condition report. This is a detailed document outlining the state of the artwork, noting any damage, repairs, or signs of deterioration such as tears, creases, water stains, mold growth, or fading. It's a standard practice and provides valuable information, especially for older or more significant pieces. For more valuable pieces, consider getting an independent appraisal to establish its market value, especially for insurance purposes or if you plan to resell in the future.

The Story and Significance

Beyond the artist's name and date, does the drawing have a story? Was it a study for a famous painting? A portrait of someone important? A sketch made during a significant event? Knowing the context can add immense depth and meaning to a piece. Sometimes, the story is simply the artist's personal note or observation on the page. These details, however small, connect you more deeply to the artwork and the moment it was created. Also consider the purpose of the drawing – was it intended as a finished piece, a quick study, or a private sketch? This context influences how you understand and value the work.

Scale and Presence

Drawings come in all sizes, from tiny thumbnail sketches that fit in your palm to monumental works on large sheets of paper. Consider how the scale impacts the drawing's presence and where you might display it. A small, intimate sketch invites close inspection, a quiet moment. A large, bold drawing can command a wall just like a painting. Think about the energy conveyed by scale – a tiny, frantic gesture drawing versus a large, meticulously rendered figure study. The artist's intent with the scale is also key; was it meant to be a small, private study or a large, public statement?

Subject Matter

The subject matter of a drawing can be incredibly varied – from quick figure studies and detailed portraits to abstract explorations of line and form, landscapes, still lifes, or even architectural plans. When collecting, consider what subjects resonate with you. A collection focused on figure studies might offer deep insights into the human form and the artist's approach to it, while a collection of abstract drawings might explore pure mark-making and composition. The subject matter often dictates the type of drawing and media used, and your personal connection to the subject is just as important as your connection to the artist's hand.

Ethical Considerations

While perhaps less common with drawings than high-value paintings, it's always wise to be mindful of the ethical considerations of collecting, especially for older works. Ensuring clear provenance helps avoid issues related to theft, illicit trade, or disputed ownership. Buying from reputable sources is the best way to navigate this. Furthermore, actively seeking out and buying directly from living artists is a wonderful ethical choice that directly supports their practice and allows you to build a personal connection. Also, be mindful of the cultural sensitivity of certain subjects or materials, ensuring you understand the context and history of the piece you are acquiring.

Double-Sided Drawings

Sometimes, a drawing exists on both sides of the paper. This can add another layer of intrigue and insight, perhaps showing an unrelated sketch on the verso or an earlier idea for the main drawing. If a drawing is double-sided, it adds complexity to framing and storage, as you might want to be able to view both sides. This is something to check for and consider when evaluating a piece.

Challenges Specific to Collecting Drawings

While drawings offer accessibility and intimacy, they also come with their own set of challenges compared to collecting paintings or sculptures. It's not all sunshine and perfect lines, you know.

Display Limitations

Paper and many drawing media are highly sensitive to light, especially direct sunlight. This means you need to be very careful about where you display them, often requiring UV-protective glass and avoiding bright, sunlit walls. This can limit your options compared to more robust media. It's a bit of a bummer when you find the perfect spot, only to realize it gets blasted by the afternoon sun.

Fragility and Handling

Works on paper are inherently fragile. They can tear, crease, or smudge easily. Proper handling with clean hands (or gloves) is crucial, and transport requires careful packing. This fragility means they might not be suitable for high-traffic areas or homes with young children or pets unless securely framed and protected. I still get a little nervous every time I move one of my unframed pieces.

Conservation Needs

As mentioned, paper is susceptible to issues like foxing, mold growth, and acid burn (yellowing). Older drawings, or those not stored archivally, may require professional conservation to stabilize them. This is an additional cost and consideration compared to, say, an oil painting on canvas. Professional conservators possess specialized knowledge, tools, and materials that allow them to safely clean, repair, and stabilize delicate paper and media without causing further damage – techniques not available to the public. It's an investment in preserving the piece for the future, but definitely something to factor in. A conservator can address issues like removing water stains, repairing tears, flattening creases, and treating mold or foxing. Deciding whether to conserve a piece often involves weighing the cost against the emotional or historical value – sometimes the signs of age are part of its story, but other times intervention is necessary to prevent further deterioration.

Where to Find Drawings and Sketches

Despite the challenges, the hunt for drawings is part of the fun! Drawings and sketches can be found in many places, sometimes in unexpected corners. It's like a treasure map, but with less 'X marks the spot' and more 'dig through this dusty flat file'.

Art Galleries

Many art galleries, both large and local art galleries, represent artists who draw. Don't hesitate to ask if they have drawings or works on paper available, even if they aren't currently on display. Often, galleries keep works on paper in portfolios or flat files, so you might need to ask specifically to see them. Best galleries for emerging artists are often great places to find affordable works on paper. Asking is key – sometimes the best pieces aren't on the wall. When possible, seeing works on paper in person is highly recommended, as it allows you to fully appreciate the texture, media, and condition in a way photos can't.

Online Marketplaces and Auctions

The online world has opened up collecting immensely. Websites dedicated to art sales, and even larger auction houses with online platforms, offer drawings and sketches. Be sure to do your research and buy from reputable sources when buying art online. Our guide to online art auctions might be helpful here. It's easier than ever to browse works from around the globe. Just be extra diligent with checking provenance and condition descriptions when buying sight unseen. It requires a bit more trust, but the access is unparalleled.

Directly from Artists

Buying directly from an artist is a wonderful way to support their work and often get a piece at a more accessible price. Many artists sell smaller works, including drawings and studies, from their studios or websites. This is something I do myself on my art for sale page. It's a personal connection that adds another layer to the piece. You might even get to hear the story behind the drawing directly from the creator. Plus, you get to see where the magic happens! (Or at least, where the pencils live.) Commissioning a drawing is another fantastic way to acquire a unique piece and build a relationship with an artist.

Art Fairs and Print Fairs

Visiting art fairs can be overwhelming, but they are fantastic places to see a lot of work from different artists and galleries in one go. Many artists and galleries will have drawings and sketches available, often in bins or portfolios, making them easier to browse and more approachable than large paintings on the wall. Don't be afraid to ask to look through portfolios – that's where the hidden gems often are. Print fairs specifically focus on works on paper, including drawings, etchings, lithographs, and more, offering a concentrated opportunity to explore this medium. It's a great way to discover new artists and see a wide range of styles.

Less Conventional Sources

Sometimes, treasures turn up in unexpected places. Estate sales, antique shops, or even online classifieds can occasionally yield interesting drawings. However, proceed with extreme caution in these venues. The likelihood of encountering fakes or works with undisclosed condition issues is much higher. You'll need to rely heavily on your own research, knowledge of the artist (if known), and a keen eye for quality and authenticity. It can be a thrilling hunt, but definitely requires extra diligence! Finding a hidden gem by an undervalued artist in a less conventional setting is a special kind of thrill, but it comes with risks. I once found a small, unsigned drawing tucked into an old book at a flea market that felt just like the style of a local artist I admired. It turned out not to be theirs, but the thrill of the possibility, the detective work, was half the fun! Buyer beware, but also, happy hunting!

Building Relationships in the Art World

Collecting drawings, especially from living artists, can be a wonderful way to build relationships within the art world. Engaging with artists directly, visiting their studios, or talking to gallerists about their drawing practice can deepen your understanding and appreciation. These connections can also lead to discovering pieces you might not find otherwise, or even commissioning a drawing yourself. It's less transactional and more about becoming part of a community. I've met some incredible people just by showing genuine interest in their process. These relationships can also provide deeper context about the specific drawings you collect, hearing the stories directly from the source. It's a rewarding aspect of collecting that goes beyond the object itself.

Caring for Your New Acquisition

Once you've found a drawing you love, proper care is essential to preserve its delicate nature. Paper is fragile, and the media can be sensitive. Treat it like the precious window into a soul that it is.

Framing and Display

Drawings on paper are susceptible to damage from touch, environmental factors, and improper handling. Professional framing is highly recommended. Use acid-free mats and backing, and consider UV-protective glass or acrylic to shield the work from light damage. Our guide on framing your artwork goes into more detail. Crucially, ensure a mat board is used to create space between the drawing's surface and the glass, preventing the medium (especially charcoal or pastel) from smudging or transferring. For unframed works, store them flat in acid-free portfolios or archival boxes, away from extreme temperatures or humidity. Remember, some media like pastel or charcoal can smudge easily, making proper framing behind glass even more crucial. When displaying, think about lighting – harsh spotlights can cause fading over time, especially with certain pigments. Diffused or indirect light is always safer. It's worth the investment to protect your piece. Also, consider the style of the frame itself – a simple, modern frame might highlight the immediacy of a sketch, while a more ornate frame could complement a detailed finished drawing. The frame is part of the presentation, not just protection.

When choosing framing glass, consider:

- Standard Glass: Offers no UV protection.

- Conservation Clear: Blocks 99% of UV rays, essential for protecting paper and pigments from fading.

- Museum Glass: Blocks 99% of UV rays and is virtually invisible due to anti-reflective coating, offering the best clarity and protection.

Environment

Avoid hanging drawings in direct sunlight (even with UV glass!) or in areas with high humidity, like bathrooms (unless specifically advised by the artist or framer). Stable temperature and humidity are best for preserving works on paper. Ideally, aim for a temperature around 70°F (21°C) and relative humidity between 40-50%. Learn more about protecting art from sunlight. Remember, paper is organic and reacts to its environment. Also, be mindful of the lightfastness of the media used; some pigments, especially in older colored pencils or pastels, can fade over time if exposed to too much light. This is why asking about materials is important! A stable environment is its best friend.

Storage for Unframed Works

If you have unframed drawings, proper storage is vital. Store them flat, never rolled, in acid-free archival folders or boxes. Use acid-free tissue paper between drawings to prevent transfer or damage. Keep these stored in a stable environment, away from attics, basements, or exterior walls where temperature and humidity fluctuate significantly. Think of it as tucking them into a safe, cozy bed. If a drawing is double-sided, consider storing it with acid-free tissue on both sides and ensuring the storage method allows you to view both sides if desired, without excessive handling.

Conservation and Restoration

If a drawing is damaged (tears, stains, foxing, creases, mold), do not attempt to fix it yourself. Consult a professional paper conservator. They have the expertise and materials to stabilize and potentially restore the artwork without causing further damage. Professional conservators use specialized techniques and materials, like specific cleaning solutions or repair tissues, that are not available or safe for the general public, ensuring the delicate paper and media are handled correctly. It's an investment in preserving the piece for the future. Learn more about when to restore artwork. A conservator can address issues like removing water stains, repairing tears, flattening creases, and treating mold or foxing.

Building a Focused Collection

As you collect, you might find yourself drawn to a particular style, artist, or subject matter. Building a focused collection can be incredibly rewarding. Perhaps you're fascinated by figure studies, architectural sketches, or the work of artists from a specific period or region. Focusing your collection allows you to become a mini-expert in that niche, deepening your appreciation and understanding. It's a journey of discovery, both of art and of your own evolving taste. Maybe you'll focus on preparatory studies for large works, or perhaps just quick gesture drawings that capture pure energy. Other ideas for a focused collection could include: drawings of a specific subject (like hands, trees, or animals), works using a particular technique (like stippling or cross-hatching), drawings from a specific art movement (like Surrealist automatism or Renaissance studies), or works by artists from a certain geographical area. The possibilities are endless, and the focus helps refine your eye and your search. It gives your collection a narrative. As your collection grows, keeping a simple inventory – noting the artist, title (if any), date, medium, size, provenance, and condition – can be incredibly helpful for organization, insurance, and future reference.

The Value of Drawings: Beyond the Price Tag

While drawings can certainly have significant monetary value, their true worth often lies elsewhere. They offer unparalleled access to the artist's mind, revealing process, thought, and emotion in a way finished works often don't. They are historical documents, capturing moments in time and the evolution of an artist's style. For me, the value is in the direct connection, the visible trace of a human hand and mind at work. It's the story the lines tell, the feeling they evoke, and the inspiration they provide. That's a value that can't be measured in dollars or euros. It's the quiet thrill of holding a piece of paper that an artist held, the tactile experience of feeling the texture of the paper and the weight of the line. It's a sensory connection to the creative moment. It's owning a piece of a soul. Collecting drawings by living artists offers a unique opportunity to engage directly with a contemporary practice, supporting their ongoing work and potentially building a personal connection that isn't possible with historical pieces.

Famous Drawers Throughout History

While paintings often steal the spotlight, many famous artists were also incredible draftsmen. Think of the detailed anatomical studies by Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci, the expressive, raw lines of Egon Schiele, or the powerful, almost frantic energy in a drawing by Jean-Michel Basquiat. But also consider Albrecht Dürer's meticulous studies, Rembrandt's expressive ink sketches, or Ingres's precise portraits. Even today, drawing remains a fundamental skill and a powerful medium for many contemporary artists. You can explore some famous sketch artists today to see the breadth of contemporary drawing and how this ancient practice continues to evolve. Drawing is the backbone of so much art, and collecting drawings is celebrating that foundation. When I look at a Da Vinci study, I'm not just seeing a perfect rendering of anatomy; I'm seeing the intense curiosity and dedication of a mind trying to understand the world through observation and line. With Schiele, it's the raw, almost uncomfortable honesty of his line that feels like a direct transmission of emotion. It's fascinating how the simple act of putting line to paper can convey so much.

Collecting Digital Drawings

In the age of digital art, drawing has also evolved. Many contemporary artists create incredible drawings using digital tools. Collecting digital drawings presents a slightly different set of considerations. Often, these are sold as limited editions, similar to prints. You'll need to understand the format, the edition size, and how the artist ensures authenticity (e.g., digital certificates, blockchain). Displaying digital drawings usually involves high-quality screens or prints, which brings us back to some of the same framing and environmental considerations as traditional drawings. It's a new frontier, but the core appeal – the artist's hand, the direct expression – remains the same. Digital drawing allows for unique possibilities, like animation or interactive elements, adding new dimensions to the concept of a 'drawing'. It's the evolution of the line, a direct mark made with light instead of pigment, but still a window into the artist's unique vision.

FAQ: Collecting Drawings & Sketches

Here are some questions I often get asked about collecting drawings:

Are drawings and sketches valuable?

Their value varies greatly depending on the artist, provenance, condition, and significance within the artist's body of work. While generally more accessible than paintings by the same artist, significant drawings by famous artists can fetch very high prices. However, many beautiful and meaningful drawings by emerging or lesser-known artists are quite affordable.

How do I know if a drawing is original?

Authenticity is key. Buy from reputable sources like established galleries, auction houses, or directly from the artist. Look for a signature, date, or any notes by the artist. Provenance (the history of ownership) is also crucial. For contemporary works, ask for a Certificate of Authenticity (COA). Don't hesitate to ask questions about the piece's origin. If in doubt, consult an expert. Researching the artist's typical drawing style and practice can also help.

Can I frame a sketch myself?

While you can, it's highly recommended to get drawings professionally framed, especially if they are valuable or on delicate paper. Professionals use acid-free materials and proper techniques to ensure the long-term preservation of the artwork. They will also use a mat board to prevent the drawing from touching the glass, which is essential for media like charcoal or pastel. Improper framing can cause irreversible damage.

How should I store unframed drawings?

Store unframed drawings flat, never rolled, in acid-free archival folders or boxes. Use acid-free tissue paper between pieces. Keep them in a stable environment, away from direct light, humidity, and extreme temperature fluctuations. Ideally, aim for around 70°F (21°C) and 40-50% relative humidity. If the drawing is double-sided, ensure the storage method protects both sides and allows for viewing if needed.

Should I insure my drawing collection?

If your collection has significant monetary value, insuring it is a wise precaution. Consult with an insurance provider specializing in art or valuable collectibles. They can advise on appraisal and coverage options.

How can I display unframed drawings or sketches?

For temporary display, you can use archival photo corners or acid-free tape to mount them onto a mat board and place them in a standard frame (ensure the frame includes a mat to prevent the drawing from touching the glass). However, for long-term preservation, professional framing with acid-free materials and UV-protective glass is always the safest option. Avoid pinning or taping drawings directly to walls, as this can cause irreversible damage.

What are common types of damage in drawings?

Common types of damage include foxing, water stains, tears, creases, mold growth, and acid burn from non-archival paper or materials. These often require professional conservation.

How are digital drawings typically displayed?

Digital drawings are often displayed as high-quality prints (which then require traditional framing and care) or on dedicated digital screens. When collecting digital drawings, you are typically acquiring a digital file or a limited edition print, and the artist or platform will provide guidance on how the work is intended to be presented and preserved.

The Joy of the Line

Collecting drawings and sketches is a deeply rewarding experience. It's a chance to connect with the artist's most direct form of expression, to own a piece of their creative journey, and to build a collection that is both personal and insightful. It's less about the grand statement and more about the intimate whisper of the line. So next time you're exploring art, take a moment to look closely at the drawings. You might just find a piece that captures your heart, a direct line to the artist's soul.

If you're curious about my own journey as an artist, you can read about it on my timeline, or explore the art I have for sale. And if you're ever near 's-Hertogenbosch, feel free to visit my museum to see some of my work in person.