Judy Chicago: Feminist Art, 'The Dinner Party,' & Enduring Legacy

Dive into Judy Chicago's revolutionary world. Explore her pioneering feminist art, the monumental 'Dinner Party,' radical education, and her lasting impact on art and social justice.

Judy Chicago: Feminist Art Pioneer, Radical Educator, and Her Indelible Seat at the Table

Sometimes, an artist doesn't just create; they completely shake up the status quo, forcing us to rethink how we see the world, history, and even ourselves. When I think about figures who didn't just make art, but made a powerful statement that echoed through culture, Judy Chicago immediately springs to mind. She's one of those rare individuals who didn't just adapt to the art world; she pretty much dared it to adapt to her, carving out an indelible seat at the table for women artists and their stories. And honestly, I find that incredibly inspiring. What does it take, I often wonder, to stand so firmly against the tide that you essentially redirect it?

Her work, particularly her monumental piece The Dinner Party, isn't just visually striking; it's a profound cultural intervention. I remember seeing images of it for the first time, and feeling this immediate sense of awe, mixed with a little bit of discomfort – which, I’ve learned, is exactly what good art should do. It challenges, it provokes, and sometimes, it even makes you a little uneasy in the best possible way. For me, exploring Judy Chicago's legacy feels like uncovering a vital, vibrant thread in the tapestry of modern art—a thread that was deliberately, and powerfully, woven by hands determined to be seen and heard, not just within the art gallery but across society. This isn't just art history; it's a blueprint for creative activism.

Who is Judy Chicago? A Force of Nature Forging Her Own Path

Born Judith Sylvia Cohen in Chicago in 1939, she grew up in an intellectually vibrant household, a backdrop that surely primed her for challenging conventions. Her father was a labor organizer and historian, instilling a deep sense of social justice and a critical perspective on power structures. Her mother, a dancer and painter, fostered creativity and an appreciation for expressive forms. This lineage, steeped in social consciousness and artistic expression, undoubtedly shaped the formidable artist she would become. Yet, the art world she entered in the 1960s was, to put it mildly, a boys' club. Think about the big names dominating the scene: the macho swagger of the Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Even incredibly talented women artists like Helen Frankenthaler or Joan Mitchell often struggled for the same recognition, frequently pigeonholed or dismissed. Judy wasn't content to simply work within those confines.

Initially, her work was more in line with the prevailing Minimalism of the era, exploring abstract forms and industrial materials. Pieces like her Car Hood sculptures—sleek, highly finished car hoods that seemed to float—were a direct engagement with male-dominated aesthetics, using materials associated with masculinity and industry. But she soon realized that simply adopting masculine styles wasn't enough to express her experience as a woman. It felt, she later articulated, like putting her ideas into someone else's language; it simply wasn't authentic to her female perspective. The formal rigor of minimalism, she found, couldn't contain the personal, emotional, and political narratives she felt compelled to explore. It was a language designed for objectivity, not for the messy, subjective, and deeply human experience she sought to articulate.

So, in 1970, she famously shed her father’s and husband’s names, adopting “Chicago” as her own. This wasn't just a casual name change; it was a deliberate, public declaration—a performance piece in itself—symbolizing her complete independence from patriarchal naming conventions and her commitment to feminism and artistic autonomy. It really personifies her entire artistic philosophy: to challenge established power structures and boldly reclaim identity. It makes you wonder, doesn't it, what parts of our identities we unknowingly inherit versus those we consciously choose to forge?

Igniting a Movement: Radical Feminist Art Education and Womanhouse

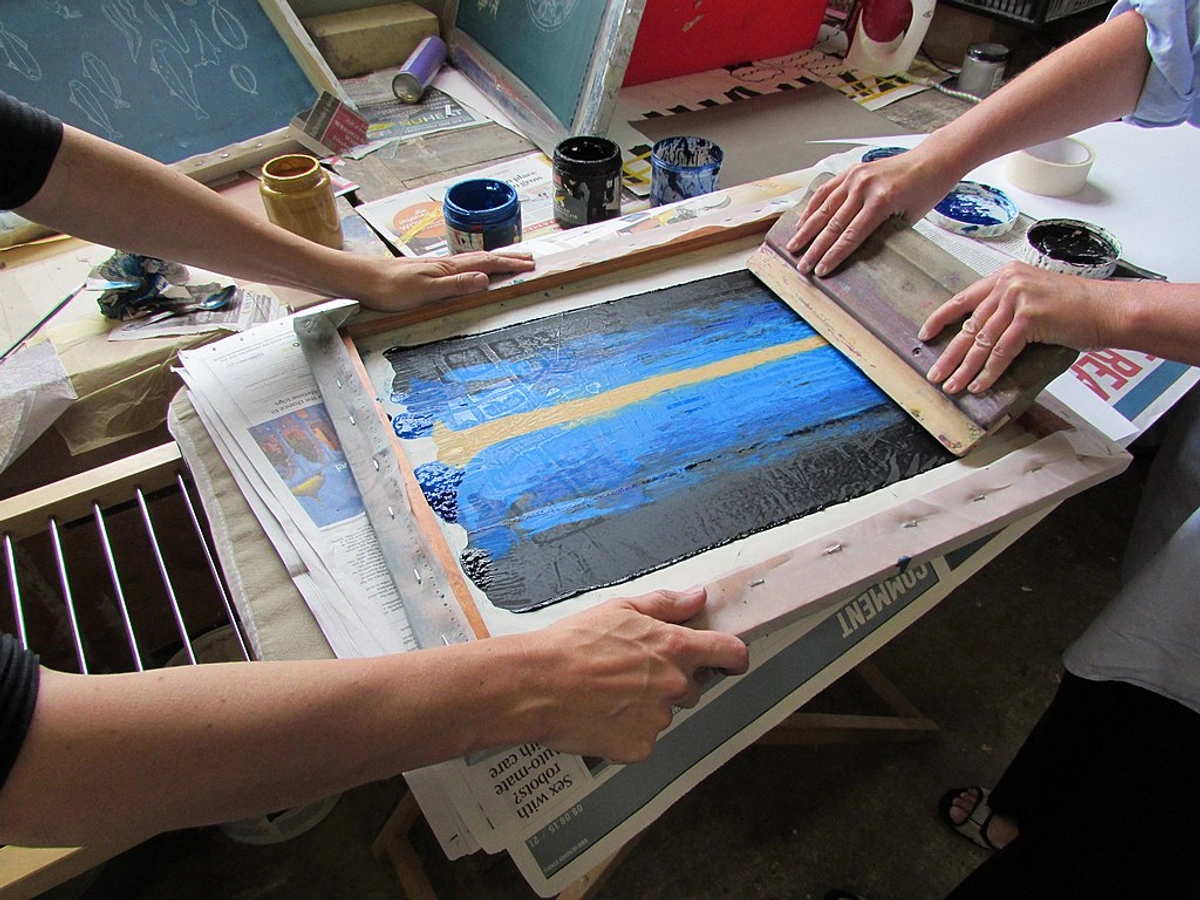

Judy Chicago didn't just critique the system; she actively built alternatives, becoming a truly radical educator. She played a pivotal role in establishing the first feminist art programs in the United States, first at California State University, Fresno (1970-71), and then at CalArts (1971-73). These weren't your typical art school classes. Imagine being in those early sessions: women artists collectively challenging centuries of male-dominated art history, critiquing the very foundations of Western art, and developing a visual language to articulate female experience. It must have been electrifying, a true intellectual and creative awakening, a space where women's voices were not just heard but amplified. I often wonder what those conversations were like, the breakthroughs and the frustrations, the sheer energy of building something entirely new. Her approach emphasized collaboration, consciousness-raising, and a focus on personal experience as valid artistic subject matter. It’s a testament to her vision that these programs paved the way for a more inclusive art education, which, let’s be honest, we still vitally need today.

One of the most radical and influential outcomes of these programs was Womanhouse in 1972. This groundbreaking collaborative art installation transformed an abandoned mansion in Los Angeles into an environment where women artists created installations addressing themes of domesticity, female identity, and traditional gender roles. It was raw, powerful, often humorous, and undeniably provocative. Think of it: a house, traditionally a women's sphere, reclaimed and reimagined as a space for artistic and feminist expression. Projects like Faith Wilding’s Waitress (a performance piece depicting the endless, thankless labor of women) or Judy Chicago’s own Menstruation Bathroom (a sterile white bathroom revealing stained feminine hygiene products) directly confronted societal expectations and hidden realities. It was a tangible manifestation of what feminist art could be: art that confronts social and political issues related to gender, often from a female perspective, and reclaims narratives previously silenced.

Key Principles of Feminist Art (as championed by Chicago)

Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Challenging the Canon | Actively questioning and revising the historically male-dominated art historical narrative, asserting the contributions and creative autonomy of women artists. |

| Reclaiming "Craft" | Elevating traditionally devalued "women’s work" (like needlework, ceramics, textile arts) to the status of fine art, thereby challenging the hierarchy of art materials and techniques and recognizing the skill involved. |

| Personal is Political | Using individual female experience—bodies, domesticity, emotions, and personal narratives—as valid and powerful subject matter for art, directly connecting these personal stories to broader political and social issues. |

| Collaboration | Fostering collective creation and authorship, often as a counterpoint to the pervasive myth of the solitary male artistic genius, emphasizing shared vision and community. |

| Female Gaze | Creating art from a woman's perspective, challenging and subverting the pervasive "male gaze" that has historically dominated the depiction of women in art, asserting female agency and subjectivity. |

The Dinner Party: An Icon, A Revolution, A Reclamation

If you know one thing about Judy Chicago, it’s probably The Dinner Party. And for good reason. It’s an installation that doesn't just demand your attention; it demands your participation, your contemplation. I remember feeling a sense of both the profound and the provocative when I first encountered it. It’s the kind of artwork that really makes you stop and think about who gets to tell history.

Conceived in 1974 and completed in 1979, The Dinner Party is a massive triangular table, 48 feet on each side, set with 39 elaborate place settings. Each setting is dedicated to a mythical or historical woman who has been overlooked or erased from history. Below the table, a ceramic tile floor, known as the Heritage Floor, bears the names of another 999 women who have contributed to Western civilization. This wasn't just her vision; it was a symphony of collective effort, with hundreds of women artists and craftswomen collaborating over five years. This monumental undertaking involved meticulously researched details for each woman, from the individual plates and goblets to the elaborate embroidered runners. By employing traditionally "female" crafts like ceramics, needlework, and embroidery on such an unprecedented scale, Chicago and her collaborators made a deliberate, powerful statement about reclaiming craft as fine art, challenging centuries of art-world snobbery.

What always strikes me about this piece is the sheer scale and the meticulous detail. Each plate, often featuring vaginal imagery (a controversial but deliberate choice to celebrate female anatomy and power), is unique and designed to reflect the woman it honors. Chicago explained that these forms were intended to represent a central core of female identity, something historically ignored or disparaged in art. The embroidered runners, crafted using traditional techniques like whitework and tapestry, were researched and executed to reflect the historical period and achievements of each woman. This explicit celebration of female sexuality and identity was revolutionary and, understandably, shocking to many at the time. It directly countered centuries of art that either ignored female anatomy or depicted it solely through a male gaze, asserting female agency and power in a way that couldn't be ignored. It's a conversation starter, to say the least.

The Controversies and Enduring Impact of The Dinner Party

From its inception, The Dinner Party sparked fervent debate. Critics questioned its artistic merit, labeling it mere craft or propaganda, a common tactic to diminish art by women. Its public funding was scrutinized, and the explicit sexual imagery often drew outrage and censorship attempts. Some feminist scholars even debated its perceived essentialism, arguing it oversimplified female experience or focused too much on a perceived universal female identity, rather than acknowledging diverse female experiences. Chicago herself often defended her choices, emphasizing the need to create a visual language that honored female bodies and contributions in a direct, unapologetic way.

Yet, these controversies only underscored its power. It became a touchstone, a symbol of feminist art's ambition and its challenge to the patriarchal art establishment. It forced conversations about gender, history, and art that simply hadn't happened on such a scale before. To this day, it remains one of the most recognized and impactful works of art of the 20th century, a permanent installation at the Brooklyn Museum, continuing to provoke and inspire generations.

Beyond the Table: Judy Chicago's Enduring Legacy and Evolving Practice

While The Dinner Party cemented her place in art history, Judy Chicago's career extended far beyond that monumental work. She is, after all, a continually evolving artist and activist. Her relentless pursuit of projects that address critical social issues is what I find truly compelling. She never rested on her laurels, always pushing the boundaries of what art can achieve and how it can serve as a catalyst for social change.

After The Dinner Party, she embarked on The Birth Project (1980–85), a series of embroidered and painted images celebrating the universal, yet often marginalized, experience of childbirth. This project, again highly collaborative, further explored themes of female experience and the reclaiming of craft. It was a powerful counter-narrative to traditional, male-dominated depictions of the female body, focusing on its generative power rather than its sexualization, bringing a deeply personal and universal experience into the realm of high art.

Later, with her husband Donald Woodman, she created The Holocaust Project: From Darkness Into Light (1985–93). This ambitious multi-media installation, combining painting, photography, stained glass, and tapestry, confronted the horrors of the Holocaust through a feminist and personal lens. It explored questions of power, oppression, and individual responsibility, moving beyond gender-specific issues to demonstrate art's capacity for profound social commentary on humanity's darkest moments. This project marked a significant expansion of her thematic concerns, showcasing her commitment to using art for ethical reflection and historical witness.

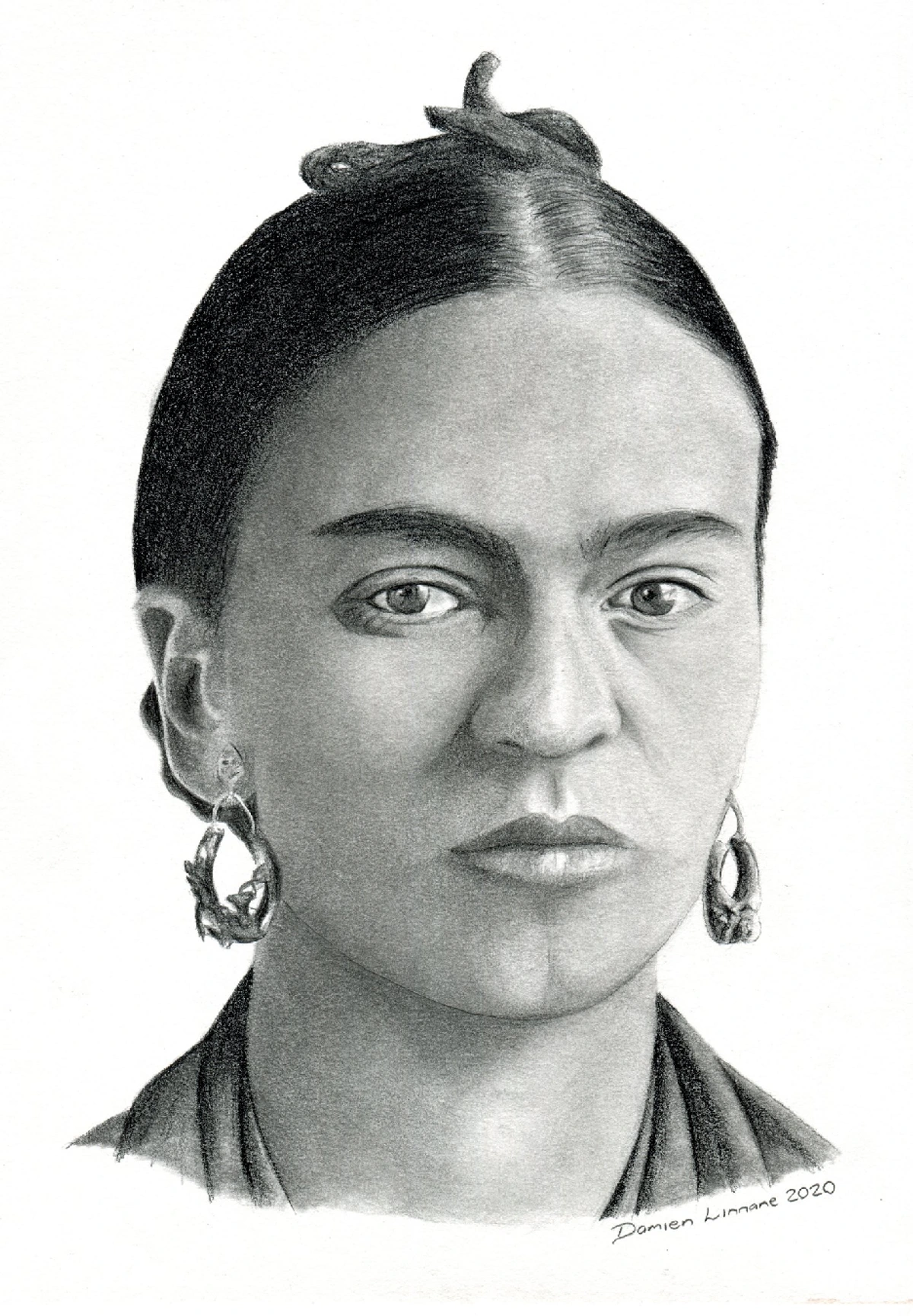

Her work continues to influence countless contemporary artists, particularly those exploring identity, gender, and social justice. Artists like Kara Walker, who critiques racial and gender stereotypes through challenging narratives and silhouettes, or Cindy Sherman, whose photographic self-portraits deconstruct female roles, can be seen as inheritors of Chicago's brave path. Even influential female artists from previous generations, like Frida Kahlo with her raw self-portraits and embrace of Mexican identity, share a spirit of challenging norms that Chicago embodies.

Her pioneering efforts to establish feminist art education, her relentless commitment to collaboration, and her unwavering belief in art as a vehicle for social change have left an indelible mark. What do you think, does an artist's personal journey, like Chicago's, resonate more deeply when it directly confronts societal norms, or when it offers a quiet, personal vision? I think for Judy, the confrontation was the vision.

Judy Chicago: Key Milestones

To fully appreciate her journey, here’s a quick overview of some pivotal moments in Judy Chicago's remarkable career:

Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1939 | Born Judith Sylvia Cohen in Chicago, Illinois. |

| 1960s | Early minimalist works, including her influential Car Hood series, engaging with male-dominated industrial aesthetics. |

| 1970 | Makes the bold statement of changing her name to Judy Chicago; establishes the first feminist art program at California State University, Fresno. |

| 1971 | Co-founds the groundbreaking feminist art program at CalArts, further expanding her radical pedagogical approach. |

| 1972 | Co-organizes Womanhouse, a pivotal collaborative feminist art installation addressing domesticity and female identity. |

| 1974-79 | Conceives, organizes, and completes The Dinner Party, her most iconic and controversial work, celebrating forgotten women. |

| 1980-85 | Develops The Birth Project, a collaborative series exploring and celebrating the often-ignored experience of childbirth. |

| 1985-93 | Collaborates on The Holocaust Project: From Darkness Into Light, a multi-media installation confronting power and oppression. |

| Present | Continues to create art, write, and advocate for art education and feminist causes globally, remaining a vital voice in contemporary art. |

Frequently Asked Questions About Judy Chicago

I get a lot of questions about artists who challenge the norm, and Judy Chicago is certainly high on that list. Here are some of the most common ones I hear:

What is Judy Chicago most known for?

Judy Chicago is most renowned for her monumental feminist art installation, The Dinner Party (1974–79). This iconic work commemorates 1,038 women from history and myth who have been overlooked or erased, providing them with a symbolic "seat at the table" and using traditionally female craft techniques on an unprecedented scale. Beyond this, she's celebrated as a pioneer of feminist art education and a lifelong advocate for women's artistic contributions, radically challenging the art historical canon.

What is the significance of The Dinner Party?

The Dinner Party is significant for several reasons: it's a groundbreaking piece of feminist art that directly challenges patriarchal narratives of history; it elevates traditionally devalued "craft" into the realm of fine art; and its explicit use of vaginal imagery reclaims female sexuality and identity from a woman's perspective, asserting female agency. It ignited widespread debate about art, gender, and representation, profoundly influencing subsequent generations of artists and scholars.

How did Judy Chicago influence feminist art?

Chicago's influence on feminist art is immense. She not only created powerful feminist artworks but also founded the first feminist art education programs in the U.S., fostering a new generation of women artists. She advocated for collective creation, challenged the art historical canon, and insisted on the validity of personal female experience as subject matter. Her work and teaching laid foundational groundwork for the entire movement, providing a blueprint for combining artistic practice with social and political activism.

What was Womanhouse?

Womanhouse was a groundbreaking collaborative art installation organized by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro in 1972. It involved students from their feminist art program transforming an abandoned Los Angeles mansion into an exhibition space. Each room became an installation or performance piece addressing domesticity, female identity, and traditional gender roles, offering a raw, often subversive, and deeply personal commentary on women's lives and societal expectations.

Is Judy Chicago still alive and working?

Yes, Judy Chicago is still very much alive and actively working! Born in 1939, she continues to create art, exhibit, write, and engage in public discourse, maintaining her role as a vital and outspoken voice in contemporary art and feminist activism. Her commitment to her vision, even into her eighties, is truly inspiring, if you ask me.

Conclusion: Her Seat at the Table, Solidified, and Waiting for You

When I look at Judy Chicago's entire body of work and her tireless advocacy, I don't just see an artist; I see a force, a catalyst, a historical corrective. She didn't wait for permission to challenge the status quo; she built new structures, articulated new visual languages, and demanded that women's contributions be recognized, celebrated, and integrated into the grand narrative of human achievement. Her journey, from navigating a male-dominated art world to creating The Dinner Party and beyond, is a testament to the power of persistence, conviction, and radical imagination. She truly carved out not just a seat, but a whole table for countless women who came after her, and continues to hold a prominent place in the conversation about art and society.

It makes me reflect on the power of one person's vision to alter the course of history, doesn't it? If you're inspired by art that challenges and provokes, I encourage you to explore more contemporary art, maybe even considering adding a piece to your own collection via our art page to /buy or visiting a museum like Den Bosch Museum. You never know what sparks might fly, or how your own path might contribute to the unfolding timeline of art. Go find your seat.