Hilma af Klint: The True Pioneer of Abstract Art & Spiritual Vision

Discover Hilma af Klint, the revolutionary artist who pioneered abstract art years before Kandinsky. Explore her spiritual journey, monumental 'Paintings for the Temple,' and how her visionary legacy is rewriting art history and impacting the art market.

Hilma af Klint: The Pioneer Who Rewrote Abstract Art History, Spiritually Speaking

I've always been a bit of a stickler for narratives, especially in art history. It's like a comfortable old sweater you pull on, knowing exactly where the worn patches are and how it fits. And for the longest time, my art history sweater had a very clear beginning for abstract art: Wassily Kandinsky. The man, the myth, the pioneer. Case closed. Or so I thought, with the charming naïveté of someone who still believes all the history books got it perfectly right. Then, Hilma af Klint walked into my artistic consciousness, not with a bang, but with a quiet, persistent whisper that slowly, then suddenly, screamed, 'Hold on a minute, you got this all wrong!' It was a delightful disruption, like finding out your quiet librarian friend is secretly a rock star. And this disruption didn't just rattle my personal understanding; it shook the very foundations of accepted art history narratives.

This wasn't just a personal revelation, a shift in my own artistic compass; her story is a powerful call to critically re-examine the very foundations of art history itself. This isn't just about dates and timelines; it's about the very foundation of what we understand about the evolution of abstract art: key movements and their collectible value. For years, the story was neatly packaged, starting with Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich. But lurking in the shadows, creating groundbreaking abstract works years before them, was Hilma af Klint. Her story isn't just a footnote; it's a vibrant, essential chapter that demands to be heard, seen, and deeply felt. Moreover, her re-evaluation isn't just academic; it has begun to significantly impact the collectible value and market perception of her work, elevating her from an overlooked visionary to a highly sought-after master. This increase in value stems from the undeniable historical precedence of her abstract work, its unique spiritual impetus, the monumental scale of her series, and its eventual recognition in major global institutions, finally placing her work in the context it always deserved. And honestly, it makes me question everything I thought I knew, in the best possible way. It's a bit like discovering a secret room in a house you thought you knew inside out, filled with treasures you never imagined.

Seeds of Abstraction: Early Life, Spirituality, and 'The Five'

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862, a time when Swedish society, like much of Europe, was grappling with seismic shifts. Rapid industrialization brought new technologies and urban growth, while groundbreaking scientific discoveries, such as Darwin's On the Origin of Species published just three years prior, challenged traditional beliefs. Amidst this upheaval, there was a growing hunger for spiritual understanding beyond conventional religion, leading to a surge of interest in movements like Theosophy (seeking universal truths in religion, science, and philosophy) and Spiritualism (belief in communicating with spirits of the dead). These movements weren't just about seeking solace; they offered a new lexicon for understanding existence, suggesting that behind the visible world lay intricate spiritual laws and dimensions. For af Klint, this meant that art could move beyond mere representation to become a direct conduit for these higher truths, a visual language for the unseen. It was also a period where societal norms often limited women's public and intellectual roles, pushing many, like Hilma, to seek alternative avenues for personal and spiritual growth. These spiritual movements, with their emphasis on individual intuition and direct experience, offered women a rare space for intellectual autonomy and leadership outside the patriarchal structures of established churches or academic institutions.

She received a rigorous, conventional artistic education at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, proving she wasn't just dabbling. She excelled at painting beautiful, naturalistic landscapes and portraits – the kind you'd expect to see hanging in any respectable parlour. But even then, I imagine her mind was already buzzing with something more, something unseen, something the Academy couldn't teach. I can almost picture her, a quiet rebel even then, her mind already sketching unseen worlds while her hands rendered the visible with perfect precision.

This wasn't just a casual interest; she dove deep into Theosophy and Spiritualism, movements that sought to reconcile science and religion, exploring hidden spiritual laws. I often wonder about the kind of dinner table conversations they had back then, probably far more profound than my usual 'Did you remember to take out the bins?' She, along with four other women artists – Anna Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson – formed 'The Five' (De Fem), a spiritualist group who regularly conducted séances. These were not mere social gatherings; they were serious spiritual experiments where they believed they communed with 'High Masters' – guiding intelligences from a higher spiritual plane – to receive messages and create art. In an era when women's intellectual and spiritual pursuits were often dismissed, this was an act of quiet, collective rebellion and profound seeking, engaging in practices like mediumship and channeling. It sounds like something out of a quirky historical novel, and yet, it was her reality, and ultimately, her artistic genesis. This collective seeking, a sort of shared artistic creative process, was where the seeds of true abstraction were sown, laying the groundwork for her most monumental individual spiritual work.

Beyond the Visible: Hilma's Revolutionary Abstract Work

Then came 1906, a year that, if I were writing her biopic, would get a dramatic, swelling soundtrack. This was when she embarked on 'The Paintings for the Temple,' a monumental series of 193 works, created under the explicit guidance of her 'High Masters.' She wasn't just sketching; she was channeling, translating complex spiritual concepts – such as duality (male/female, light/dark), the evolution of humanity, creation, and spiritual concepts of unity and interconnectedness – into forms and colors that defied the artistic conventions of her era. It’s like being told to paint the very essence of a spiritual journey, not a landscape, but doing it with such conviction that these abstract forms become more real and resonant than any physical representation. The sheer scale of these works, often tempera on paper mounted on canvas, was itself revolutionary, with some pieces reaching monumental dimensions, a scale almost unheard of for women artists at the time.

Among these, 'The Ten Largest' stand out – immense, vibrant canvases (up to 3.2m x 2.4m each) depicting the stages of human life, from childhood to old age. They burst with organic forms, spirals, circles, and an intoxicating palette of pinks, oranges, blues, and yellows, using a visual language that felt both ancient and futuristic. Looking at them, it's hard not to feel a connection, a resonance. It makes you think about the psychology of color in abstract art and how she instinctively tapped into something universal. Her process wasn't simply intuitive; it was a disciplined, almost scientific mapping of the spiritual realm, a meticulous record of unseen forces. If I tried to do that, it would probably look like a toddler's temper tantrum on canvas, bless her genius.

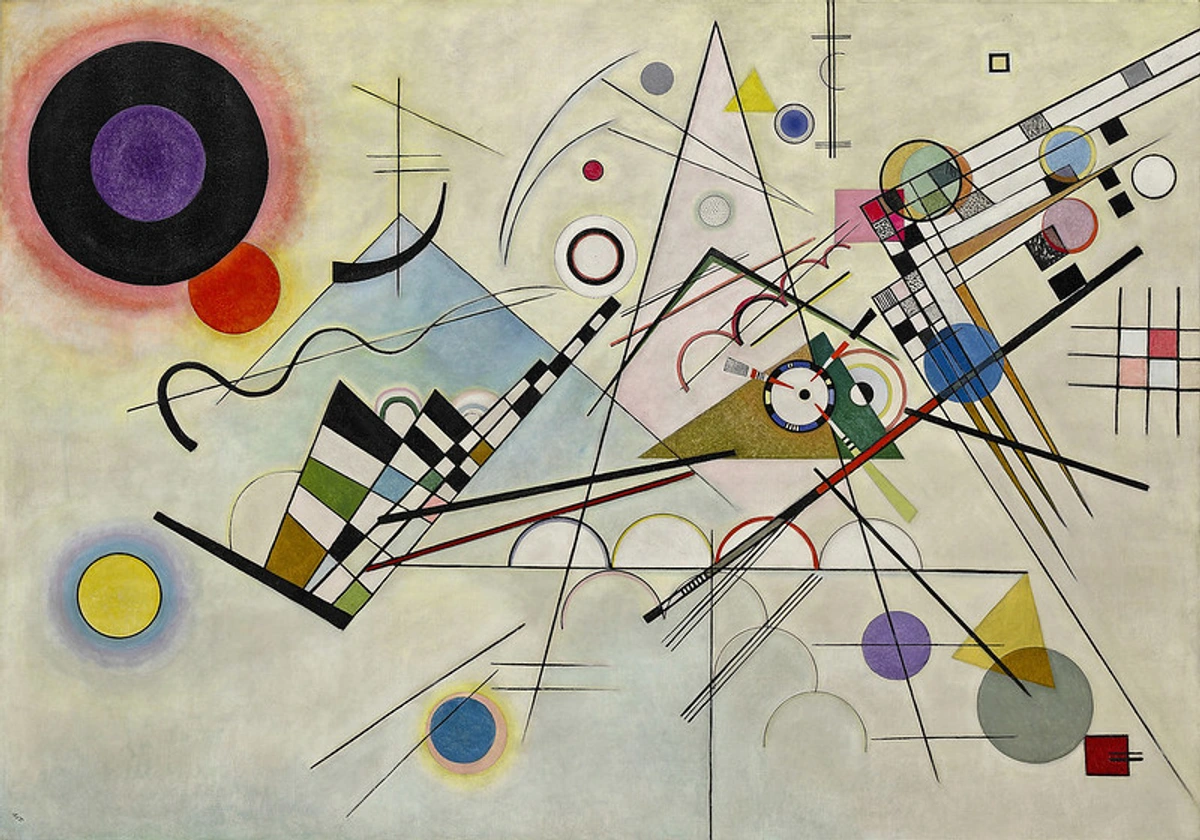

The truly mind-boggling part? She was creating these works, pure abstract art, years before Kandinsky exhibited his first abstract paintings. Think about that for a second. While the accepted 'father' of abstraction, Wassily Kandinsky, was still transitioning from Symbolist landscapes to Expressionism, exploring the theoretical underpinnings of abstraction in works like his 1911 treatise 'Concerning the Spiritual in Art' (which conceptualized how art could serve spiritual ends through abstract forms and colors, aiming to distill universal spiritual truths into a visual language), Hilma was already swimming in the deep end of non-representational art, guided by an intense spiritual conviction. Kandinsky, in his seminal 1911 treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, laid out a theoretical framework for abstract art, advocating for a move away from the material to the spiritual through non-representational forms and colors. He believed in art's capacity to resonate with the 'inner sound' of the soul, aiming for a universal spiritual language. But while he was theorizing about this, Hilma was already doing it, driven by direct spiritual guidance and an almost scientific precision in mapping the spiritual realm. She didn't just dabble in abstract forms; she employed a complex, systematic symbolic language of shapes, colors, and lines to convey profound metaphysical concepts, charting unknown spiritual territories with an almost scientific precision. It challenges the very history of abstract art we've been taught. Her work had already been there for years, not just exploring abstraction but defining it, driven not by aesthetic theory but by a profound spiritual imperative, establishing her as the undeniable pioneer. The sheer audacity of her vision, developed in relative isolation, is what truly sets her apart. While Kandinsky theorized about the spiritual in art, Hilma lived it, painting its very essence directly from unseen realms. And it makes you wonder: what does it mean for art history when the 'pioneers' are not the ones we've been taught?

A Vision for the Future: Anthroposophy and a Legacy of Secrecy

But what happens when one's deeply personal spiritual quest crosses paths with an established philosophical leader? Hilma's spiritual journey continued, evolving to include Anthroposophy, the philosophy founded by Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophy, meaning 'wisdom of the human being,' is a spiritual movement that aims to connect the spiritual world with the intellectual realm through inner development and experience. Steiner often saw art as a vital vehicle for spiritual education, though usually advocating for forms that were more symbolic or figurative rather than purely abstract in the initial stages of spiritual understanding. She met Steiner, hoping for recognition and understanding of her radical work. His reaction was... complicated. While he acknowledged her spiritual insights, he suggested her work was not yet ready for public consumption, finding it too abstract and perhaps too ahead of its time. Steiner, while a profound spiritual thinker, was also pragmatic about public reception. He saw abstract art as potentially disorienting if presented without the 'interpretive keys' of symbolic or figurative guidance first. He believed her work, raw and direct from the spiritual plane, lacked the conventional symbolic framework he thought necessary for the public to grasp such profound spiritual truths at that time. Imagine pouring your soul into hundreds of paintings, convinced they held profound truths, only for a respected spiritual leader to essentially say, 'Not yet, dear.' It would be crushing, wouldn't it? It reminds me of a time I showed an unfinished piece to a mentor, brimming with excitement, only to hear, 'It's got potential, but it's not quite there yet for others to truly see what you see.' It's a humbling, even painful, kind of feedback, especially when you feel it's the truest thing you've ever created. A bit like showing off your new abstract art for sale at an exhibition only to be met with polite, puzzled silence, and a gentle pat on the head.

This feedback, coupled with her own unwavering conviction that the world wasn't ready to grasp her spiritual language, ultimately shaped her monumental decision regarding her legacy. She deeply believed that the public and critics of her time lacked the spiritual or intellectual framework to truly comprehend her work. The abstract forms and vibrant colors, so intimately tied to profound spiritual messages, would simply be seen as aesthetic curiosities, not the cosmic revelations she intended. Her decision to withhold her art was an act of profound foresight and protection – safeguarding the integrity of her spiritual message until humanity was spiritually and intellectually mature enough to receive it. She stipulated that her abstract works should not be shown publicly until 20 years after her death. That's a profound act of self-belief mixed with an almost painful understanding of human limitations. It makes me reflect on my own journey, documented in my timeline, and wonder what future me will cherish or regret. She understood that her art required a different kind of eye, a different kind of mind, one attuned to decoding abstract art through a spiritual lens. It was an act of both protection and prophecy.

An Evolving Vision: Later Works and Continued Exploration

While 'The Paintings for the Temple' represent her most recognized abstract breakthrough, Hilma af Klint's artistic and spiritual explorations continued throughout her life. Following this monumental series, she embarked on other significant abstract collections such as the 'Swan' series (1914-1915), which explored themes of duality, metamorphosis, and spiritual evolution, often featuring intertwining, dynamic forms in contrasting colors like black and white, and later, blues and pinks. The 'Swan' series, for instance, dramatically explores the duality of existence—light and dark, masculine and feminine—through intertwined forms and contrasting colors, often morphing from sharp black and white into softer blues and pinks, illustrating spiritual evolution. She also created the 'Altarpieces' (1915), three large, brilliantly colored abstract works intended for her spiritual 'Temple,' symbolizing spiritual ascent and the union of material and spiritual realms through ascending geometric forms and radiating light. The 'Altarpieces,' on the other hand, are three magnificent works designed for her envisioned Temple, using ascending geometric forms and radiating light to symbolize spiritual ascent and the harmonious union of the material and spiritual. These works further refined her visual language, often incorporating more structured geometric forms and symbolic representations, typically executed in tempera on paper or canvas.

In her later years, especially after 1915, her work sometimes became more symbolic and even returned to a more figurative, yet still deeply spiritual, style. She created series depicting shells, flowers, and portraits, all infused with her Theosophical and Anthroposophical understandings. This evolution demonstrates a continuous quest for expressing spiritual truths through diverse artistic means, proving her dedication wasn't confined to a single style. It makes me ponder my own artistic evolution, how my style shifts and flows, sometimes revisiting earlier themes, always seeking new ways to express the inexpressible. Does your own creative journey ever feel like that? It's a powerful reminder that an artist's journey is rarely linear, and that exploration is as vital as discovery. Do you find comfort in a consistent style, or is the thrill in constant evolution?

Hilma's Enduring Legacy: Rewriting Art History

True to her will, her abstract works remained largely unseen for decades after her passing in 1944. Even when her work first began to emerge in the 1980s, it often faced categorization as 'spiritual art,' limiting its recognition within mainstream art history. Critics and scholars lacked the contextual framework to understand her pioneering abstract approach, which was so far removed from the dominant narratives of abstraction's origins. It took decades for the art world to recalibrate, to see her not just as a spiritualist, but as a monumental artist whose historical precedence was undeniable. However, it was truly exploding in the 21st century that the art world caught up to Hilma. Pivotal moments included the 2013-2014 exhibition at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, which then traveled to several major European cities, and most notably, the record-breaking 2018-2019 exhibition, "Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future," at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. This exhibition, drawing over 600,000 visitors, cemented her status globally. The sheer scale, visionary nature, and early dating of her art stunned critics and the public alike, forcing a dramatic re-evaluation of the definitive guide to understanding abstract art and its origins. Her powerful narrative has also started to influence contemporary artists, expanding the dialogue around the role of spirituality and unseen forces in modern and abstract art.

Her extensive oeuvre is managed by The Hilma af Klint Foundation, established by her nephew Erik af Klint, which plays a crucial role not only in preserving her art and organizing exhibitions worldwide but also in fostering comprehensive research and educational initiatives, ensuring her vision continues to inspire. Her legacy is immense. She didn't just paint abstractly; she painted from a place of deep conviction, proving that abstraction wasn't merely an aesthetic choice but could be a profound spiritual expression. For contemporary artists, myself included, her story is a beacon. It's a reminder to trust your inner vision, even if the world isn't ready for it yet. It encourages a fearless approach to color and form, much like the vibrant pieces you might see in my own Den Bosch museum. Hilma af Klint’s journey is a powerful testament to artistic resilience, spiritual courage, and the undeniable fact that sometimes, the future just needs a little time to catch up. What lessons do you take from her unwavering commitment to an unacknowledged vision?

Frequently Asked Questions About Hilma af Klint

- Why is Hilma af Klint considered a pioneer of abstract art? She created her first purely abstract paintings in 1906, years before artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich, who are traditionally credited with pioneering abstract art. Her work stemmed from a spiritual rather than purely aesthetic or theoretical impulse, setting a completely new precedent.

- What was The Five (De Fem)? De Fem (The Five) was a group of five women artists, including af Klint, who shared a deep interest in spiritualism and Theosophy. They held séances and practiced automatic drawing and painting, believing they were conduits for messages from 'High Masters' – guiding spiritual intelligences.

- What role did spirituality play in her art? Spirituality was the central driving force behind Hilma af Klint's abstract art. She believed her paintings were not merely artistic creations but visual interpretations of profound spiritual concepts and messages received from her 'High Masters' during her spiritualist sessions, making her art a form of spiritual communication.

- What materials and techniques did Hilma af Klint use? She primarily worked with tempera on paper, often mounted on canvas, allowing for rich, matte colors. Her technique involved automatic drawing and painting, but also meticulous planning and a sophisticated symbolic language, often using geometric forms, spirals, and vibrant color palettes (like the striking pinks and blues of 'The Ten Largest') to represent spiritual concepts. Notably, her works frequently reached monumental scales, with 'The Ten Largest' being prime examples, a scale almost unheard of for women artists of her time.

- Why did Hilma af Klint request her abstract works to be kept secret for 20 years after her death? Af Klint believed the world was not ready to understand or appreciate the profound spiritual meaning embedded in her abstract works during her lifetime. She felt her art required a deeper spiritual and intellectual comprehension that would only develop with time, hence the secrecy clause in her will. It was an act of protecting her vision and ensuring its eventual, proper reception.

- Where can I see Hilma af Klint's work today? Her work has been exhibited globally in major museums, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Serpentine Gallery in London. Her extensive oeuvre is managed and promoted by The Hilma af Klint Foundation, which continues to organize exhibitions and research her legacy.

- How was Hilma af Klint's work initially received? When her work first received limited exposure in the 1980s, it was largely categorized under spiritual or esoteric art, often overlooked by the mainstream art world. Critics and scholars lacked the contextual framework to understand her pioneering abstract approach, which was so far removed from the dominant narratives of abstraction's origins. It took sustained effort from her foundation and a global re-evaluation for her true significance to be recognized.

My Final Thoughts: A Reminder to Look Deeper, Spiritually Speaking

So, what does Hilma af Klint's story teach us? For me, it’s a powerful reminder to question the narratives we’re fed, to dig a little deeper, and to celebrate the quiet revolutionaries who often precede the loud ones. Her journey, her unwavering belief in her vision despite the lack of contemporary recognition, is profoundly inspiring. It reinforces my own conviction to explore the unseen, the emotional, the intuitive, and the spiritual in my art, much like the pieces you find in my art for sale or the stories I share from my artistic timeline. Her dedication to abstract forms as a conduit for spiritual messages resonates deeply with my own desire to imbue my abstract art with meaning beyond mere aesthetics. And honestly, it makes me wonder how many other unacknowledged geniuses are out there, quietly shaping the future while the spotlight is elsewhere. A humbling thought, indeed.

Hilma af Klint didn't just paint pictures; she painted a new path, a vibrant testament to the power of inner vision, and for that, I am eternally grateful. She reminds me that true creation is often a conversation between the artist and something much larger, a whisper across time, waiting for the right moment to be heard. It's like finding a new, more intricate pattern in that old art history sweater, a pattern that was always there, just waiting to be seen. What hidden patterns are waiting in your own life's narrative?