Fresco Painting: A Curator's Journey Through Ancient Walls and Artistic Ambition

Dive into the world of fresco painting, from ancient techniques and monumental masterpieces to its enduring legacy. Explore how artists and patrons fused vision into architecture for millennia.

Fresco Painting: A Curator's Journey Through Ancient Walls and Artistic Ambition

You know, sometimes I look at a painting and it's not just the colors or the subject that grab me; it's the sheer audacity of it. Fresco painting, for me, embodies that audacious ambition like few other art forms. It's an intricate dance with drying plaster, a nerve-wracking race against time, and a profound testament to human ingenuity that has, quite literally, stood for millennia. I've always been captivated by how these incredible murals survive, whispering stories from ancient walls, constantly challenging our modern perceptions of permanence. In this journey, we'll dive into the captivating world of fresco, from its very first whispers in antiquity to its powerful legacy, uncovering the secrets behind its remarkable permanence, its immense artistic power, and, perhaps most importantly, what it reveals about human ambition – not just of the artists, but of the powerful patrons who commissioned these indelible, often political, statements.

The Alchemy of the Wall: Unraveling Fresco Techniques

Before we even get to the intricate 'how,' let's talk about the 'why.' For thousands of years, fresco wasn't simply decoration; it was storytelling on a monumental canvas, a public stage for myths, histories, and spiritual narratives. These were often commissioned by powerful entities – think the Church or immensely wealthy families – to assert their faith, authority, and to literally etch their legacy into the fabric of society for generations to come. How did they manage such lasting impact? Well, that brings us to the fascinating, and if I'm honest, somewhat terrifying, alchemy of the wall itself.

When I first learned about fresco painting, I remember thinking, 'Wait, you're painting into wet plaster?' It sounds daunting, right? And trust me, it absolutely is. Essentially, we're dealing with two primary methods: Buon Fresco (true fresco) and Fresco Secco (dry fresco).

Buon Fresco (True Fresco): The Art of Chemical Bonding and High Stakes

Buon Fresco is where the real magic, and the real challenge, unfolds. Picture this: an artist has to work incredibly fast, often racing the clock, applying pigment directly onto a freshly prepared layer of wet plaster, known as the intonaco. This intonaco is a very fine, smooth topcoat, typically made from specially slaked lime and fine river sand. It's applied over a coarser, foundational underlayer called the arriccio. The arriccio isn't just a rough base; it’s a crucial component. Made from coarser sand and lime, it provides a strong mechanical bond for the intonaco and helps regulate moisture. It’s also often where the sinopia – a preliminary drawing made with red earth pigment – is laid out, serving as the artist's foundational blueprint for the entire composition. The precise quality of this plaster mix, its texture, and its moisture content are paramount; too dry, and the pigment won't bind chemically; too wet, and it might run or cause efflorescence. Masters often incorporated different aggregates like volcanic ash (pozzolana in ancient Rome) or marble dust (favored during the Renaissance) into their plaster mixes, each contributing subtly different qualities to the final artwork's texture, absorbency, and ultimate durability, often tailored to the local climate and available materials. The sinopia itself, frequently revealed during meticulous restorations, offers a powerful, raw glimpse into the artist's original vision, a foundational blueprint etched directly onto the wall before the final layers ever touched it. For a deeper dive into the nuances of this fascinating process, you might enjoy exploring more about what fresco painting is all about.

The truly nerve-wracking part? You can only apply as much intonaco as you can paint in one session – these daily sections are called giornate (meaning 'a day's work'). For someone like me, who sometimes struggles to even finish a single email in one sitting, the idea of having to complete a flawless section of a monumental artwork before the plaster sets is, frankly, terrifying. It's an artistic sprint against nature, demanding immense physical stamina, precise planning, and unwavering focus – a universe away from the thoughtful, iterative process of oil painting or, for that matter, the undo button of digital art. There's just no room for error, no second guesses, just pure, decisive artistry. Talk about creative pressure! And let's not forget the sheer logistics: imagine constructing intricate scaffolding, often for years, and then painting overhead, sometimes on your back, like Michelangelo famously did in the Sistine Chapel. That’s a whole other level of dedication, physical strain, and vision!

As the plaster dries, a truly remarkable chemical reaction occurs. The calcium hydroxide in the wet lime plaster reacts with carbon dioxide in the air, forming calcium carbonate. This process, known as carbonation, permanently binds the pigment to the wall. It’s like the wall itself becomes the canvas, an inseparable part of the architecture, chemically locking the colors into the stone. To me, that's mind-bogglingly cool – like minerals slowly forming in a cave, becoming one with the rock over eons. This is also why fresco artists traditionally used natural earth pigments – mineral-based pigments like red ochre (from hematite), yellow ochre (from limonite), carbon blacks, and various greens (derived from iron oxides). These pigments are incredibly stable in the alkaline environment of the wet lime plaster, meaning they won't chemically degrade or change color. More vibrant or delicate colors, such as blues (like precious ultramarine, derived from lapis lazuli, which was historically incredibly expensive and rare) and certain greens or reds, were far more challenging to use in true buon fresco. This was either due to their chemical instability in the alkaline environment (they might react and discolour) or their exorbitant cost. Achieving subtle gradations or very fine details was also inherently difficult with the rapid drying time, often requiring artists to work in broader strokes and rely on the viewer's distance to create the illusion of detail. These vibrant colors were often added a secco (on dry plaster) later, a compromise that, as we'll soon see, came with its own set of durability issues. This limitation in the buon fresco palette is a fascinating challenge, especially for someone like me who loves to explore a full spectrum of abstract color in my own work; it makes me appreciate the ingenuity and resourcefulness of these ancient artists even more.

Fresco Secco (Dry Fresco): Flexibility with a Frail Trade-off

Fresco Secco, on the other hand, involves painting onto dry plaster. While it offers significantly more flexibility and allows for greater detail or corrections (a luxury I can certainly appreciate in my own artistic process, especially compared to buon fresco's unforgiving nature!), it critically lacks the incredible durability of true buon fresco. Here, the paint sits on the surface rather than becoming chemically integrated into the wall. Artists would use a binding medium like animal glue, egg yolk, or casein, which unfortunately deteriorates over time. These organic binders don't chemically bond with the wall; they merely adhere to the surface, making them highly susceptible to humidity changes, light exposure, and even microorganisms. This is why many secco elements, like the vibrant blues of Giotto's frescoes at the Scrovegni Chapel, have deteriorated or flaked away over time, leaving us with tantalizing hints of their former glory, and presenting a constant, often uphill, battle for conservators. It's a vivid reminder that sometimes, the easiest path isn't always the most enduring.

To make it a little clearer, here’s a quick comparison of these demanding techniques:

Feature | Buon Fresco (True Fresco) | Fresco Secco (Dry Fresco) |

|---|---|---|

| Plaster State | Wet (intonaco) | Dry |

| Binding | Chemical reaction (carbonation) | Organic binder (glue, egg, casein) |

| Durability | Extremely high, permanent | Low, prone to flaking and fading |

| Working Speed | Fast, no room for error | Slower, allows for corrections and detail |

| Pigments | Earth pigments (alkali-resistant) | Wider range of pigments, including unstable ones |

| Artistic Control | Less (must work fast, broad strokes) | More (can add fine detail, correct, blend) |

Whispers from Antiquity: Where Fresco First Found Its Voice

Having understood the fundamental mechanics, let's journey back to where this incredible art form first began to whisper its stories. My mind often wanders to the earliest known examples of fresco. We're talking Minoans here, over 3,500 years ago, on the island of Crete, creating vibrant scenes that somehow still captivate us with their dynamic energy and fluid forms – often depicting natural scenes, elaborate ceremonies, and daring bull-leaping rituals. The Egyptians, too, employed sophisticated forms of wall painting, demonstrating incredible mastery of durable pigments and complex compositions, even if not always true buon fresco in the strictest sense.

Moving further, the Etruscans left us breathtaking tomb paintings, like those at Tarquinia, which offer intimate glimpses into their funerary rites and daily lives, infused with a poignant sense of humanity. And then, as Christianity emerged, we find frescoes in the Roman catacombs, illustrating early biblical narratives and symbols, often with a touching simplicity and spiritual fervor. There's a particular magic in these early works; the raw energy, the almost naive directness of their storytelling that feels so profoundly human, bridging vast stretches of time to connect with our contemporary emotions. As the Roman Empire evolved and embraced Christianity, the art form continued to adapt, with Byzantine frescoes, for instance, developing distinct iconic styles and theological narratives, further solidifying the wall painting tradition through the early medieval period.

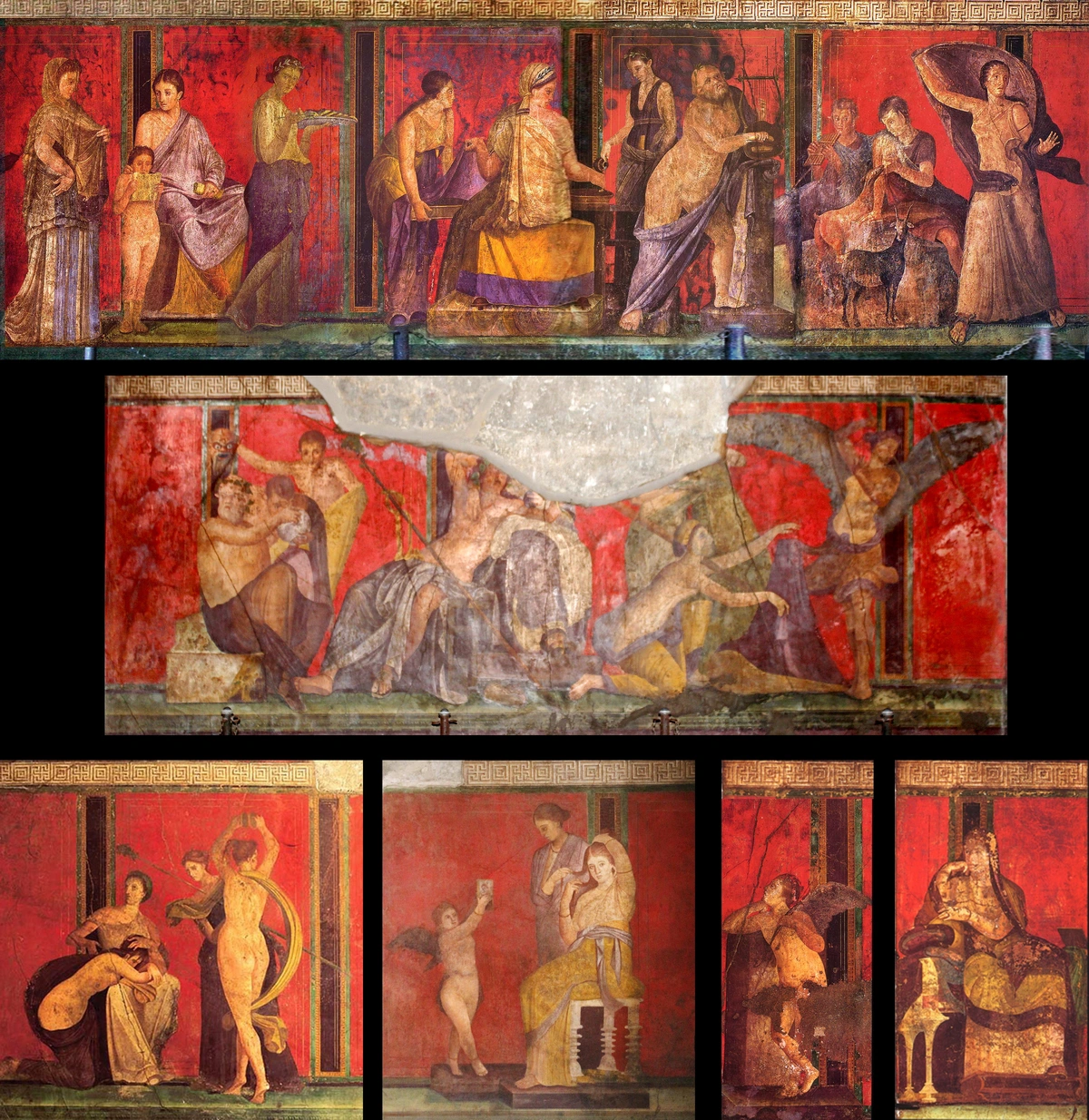

But it's the Romans who truly bring the ancient world alive for me through fresco. Their works from Pompeii and Herculaneum, miraculously preserved by volcanic ash, are like a vibrant snapshot into their daily lives, their myths, their very souls. It’s an almost unnerving feeling, standing before something so ancient and yet so vivid. You can almost hear the chatter, the clinking of goblets, the rumble of a chariot passing by. Roman fresco painters developed distinct styles, moving from the First Style's imitation of marble, to the grand architectural vistas of the Second Style, the delicate ornamentation and mythic scenes of the Third Style, and the eclectic mixes of the Fourth Style, often combining elements of the others. The plasters themselves often incorporated varying proportions of lime, sand, and sometimes crushed marble or brick dust, affecting their texture and working properties – a testament to the regional and chronological adaptations of this core technique. Each style tells a different story about their evolving aesthetic, and we even see examples of non-mythological subjects, such as portraits or everyday life scenes, reminding us of the broad application of this art form. I mean, look at this chariot race – the dynamism, the sheer energy, captured forever on a wall that was buried for nearly two millennia.

And then there's the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, a truly breathtaking example. The scale, the rich, Pompeian red, the enigmatic rituals depicted – possibly relating to the Dionysian mysteries – make it profoundly immersive. Standing in that room, you don't just observe the art; you become part of the story, transported to a world long past, connected by the shared human experience of belief and ceremony. It's a powerful reminder of art's profound ability to connect us across vast stretches of time.

These ancient artisans, with their meticulous preparation of plaster and pigment, laid the groundwork for future generations. Their commitment to embedding art directly into architecture would find its most ambitious and celebrated expression in the period that followed: the Renaissance.

The Renaissance Rebirth: A Golden Age of Fresco and Patron Power

If antiquity laid the foundation, then the Renaissance truly built the soaring cathedral of fresco, didn't it? This was when wall painting ascended to its most celebrated and ambitious heights, an era driven by a renewed humanism, profound spiritual ambition, and the immense power of patrons. These weren't just decorative commissions; wealthy families and the Church saw frescoes as monumental statements of faith, authority, and legacy – often explicitly designed as propaganda or didactic tools to shape public belief and glorify their power. Artists like Giotto started giving their figures a new sense of weight and emotion, moving away from flatter, more symbolic representations. He was revolutionary in imbuing his figures with volume and human feeling, making them feel like real people with real burdens, not just symbols. Then came Masaccio, pushing boundaries with linear perspective, making us feel like we could step right into his scenes, transforming a flat wall into a convincing illusion of space. Other masters, like Fra Angelico, brought serene beauty and spiritual depth to monastery walls, showcasing the varied artistic expressions within the same challenging medium. Each stroke was a commitment, a definitive mark on history; it meant not just technical skill but also immense foresight, having to envision the final piece from start to finish within those brief giornate. These immense projects were rarely solitary endeavors, often requiring large workshops of skilled assistants to prepare plasters, grind pigments, construct scaffolding, and even execute less critical sections under the master's precise direction. This collaborative effort was crucial for the sheer scale and speed demanded by fresco.

And, of course, the titan himself, Michelangelo. His work in the Sistine Chapel Ceiling Frescoes isn't just art; it's an entire universe. I remember standing there, neck craned, feeling utterly dwarfed by the scale and majesty of it all. Beyond the immense artistic skill, it’s an act of profound faith, a conversation with the divine, immortalized in plaster. You can almost feel the aches in his neck and back, the sheer grit required to paint for years overhead, literally fusing his spiritual vision into the very architecture of the Vatican. It was a monumental effort that must have pushed the limits of human endurance and artistic vision, a testament to what a single human can achieve when driven by an almost superhuman force. Beyond Michelangelo, other masters like Raphael, whose frescoes in the Vatican's Stanze (Raphael Rooms) display unparalleled grace and intellectual depth, further defined this golden age. It makes me reflect on my own artistic ambitions; while I work on a smaller scale, that drive to create something meaningful, something that feels like a conversation with an unseen force, is a shared human experience across millennia, isn't it?

The Vatican, as a whole, is a treasure trove of these incredible works. Everywhere you look, there's a story told in pigment and plaster, a history etched into the very fabric of the building. It's overwhelming, in the best possible way. Each fresco tells a specific narrative, often commissioned to convey power, spirituality, or historical events, meticulously planned and executed, serving as a constant visual sermon or a glorification of the commissioning patron – a public art form designed to shape belief and convey authority.

credit, licence

The Renaissance perfected the art of fresco, but the next era would take its illusionistic potential to dizzying, awe-inspiring new heights.

Baroque Grandeur and Modern Echoes: The Enduring Spirit of Wall Art

The legacy of fresco certainly didn't stop with the Renaissance, of course. In fact, if the Renaissance was about divine truth and human potential, the Baroque period, with its dramatic flair and theatricality, took fresco to new heights of illusionism, literally bending reality to overwhelm the senses. Think grand ceilings that seem to dissolve into open skies, with angels and gods swirling above you, pulling your gaze upwards into a theatrical paradise. Artists like Correggio, with his pioneering illusionistic domes (such as in Parma Cathedral), laid crucial groundwork, which was then dramatically expanded upon by masters like Pietro da Cortona (with his Palazzo Barberini ceiling) and Andrea Pozzo. These artists achieved breathtaking effects through sophisticated techniques like quadratura – a painting technique designed to extend architectural space visually, making painted elements appear as three-dimensional extensions of the actual building, often using extreme foreshortening to make figures burst forth or recede into infinite space. The Palazzo Barberini fresco ceiling by Pietro da Cortona is a prime example of this dazzling spectacle, a masterpiece of trompe-l'œil that makes you realize art isn't just about painting a picture; it's about transforming space, bending reality, creating an immersive experience that overwhelms the senses. What an incredible feat of engineering and artistry! This wasn't just art; it was a powerful statement of wealth, status, and often, religious triumph, effectively functioning as grand public relations for the patrons, making the spiritual and political tangible and awe-inspiring.

Even in the opulent chambers of the Vatican, these dramatic stylistic shifts were evident, transforming mere surfaces into windows to other worlds, often populated by angelic figures or momentous historical scenes, all designed to inspire awe and devotion.

And while perhaps less common today in its strictest traditional form – let's be honest, few people are building cathedrals and palaces that need epic frescoes anymore – the spirit of fresco, the idea of art embedded within architecture, lives on. Contemporary artists explore similar themes of permanence, public art, and the dialogue between art and structure. I've seen modern murals, like the vibrant work by Slovak artists Peter and Ivan Mester, and grand public art installations in urban spaces worldwide that, even without the wet plaster technique, evoke that same sense of grand scale and commitment. Artists today use everything from aerosols to mosaics, and even advanced acrylic paints with specialized sealants to achieve impressive durability, mimicking the long-lasting effect of fresco and its integration with architecture. Consider the monumental public art of artists like Diego Rivera, whose powerful murals in Mexico and the United States, though often executed with modern pigments on various surfaces, undeniably carry the thematic and grand-scale legacy of fresco, embedding social and historical narratives directly into civic architecture. It’s a testament to the idea that the ambition to create site-specific work that communicates with a public, defines a space, and hopefully endures, continues to thrive, evolving with new materials and contexts.

For someone like me, who creates art that often exists on a canvas and then as a print to buy for a fleeting moment in a gallery or a home, there's a particular reverence for works that are so intrinsically tied to their physical location, becoming part of the building itself, rather than existing as a movable object. My abstract pieces, though not frescoes, strive for a similar kind of resonance – an emotional permanence, an integration of color and form that aims to transform a space. While I work in a fast-paced world of digital art and printmaking, the underlying desire for my art to speak across time, to have a lasting impact beyond a fleeting moment, echoes the ancient fresco masters. It's a different kind of permanence, I suppose, one that doesn't just hang on a wall but is the wall, or at least aims to deeply impact the perception of it.

Frequently Asked Questions About Fresco Painting

Curiosity is a wonderful thing, and I often find myself pondering the same questions about these incredible works. Here are some of the most common inquiries I encounter:

What is the main difference between buon fresco and fresco secco?

Buon fresco (true fresco) involves painting on wet, fresh plaster, where the pigments chemically bond with the wall as it dries, creating an extremely durable and long-lasting artwork. Fresco secco (dry fresco) means painting on dry plaster, using a binding medium. This allows for more detail and corrections but is significantly less durable and prone to flaking over time, especially due to environmental factors and the organic nature of its binders.

How long does a fresco last?

When executed correctly, buon frescoes can astonishingly last for thousands of years, given proper care and stable environmental conditions. Their incredible durability is one of their most remarkable characteristics; many ancient Roman and Renaissance frescoes still captivate audiences today. However, this longevity is always a precarious balance. Many have been lost or severely degraded over centuries due to environmental factors, pollution, seismic activity, and even poorly executed past restorations, making their survival a testament to both their inherent durability and continuous human efforts in conservation.

How durable is fresco secco compared to buon fresco?

Fresco secco is significantly less durable than buon fresco. While buon fresco's pigments become chemically integrated into the wall, fresco secco relies on organic binders (like animal glue, egg yolk, or casein) that sit on the plaster's surface. These binders are highly susceptible to moisture, temperature changes, and biological degradation, leading to flaking, fading, and deterioration over a much shorter period, often decades or centuries rather than millennia.

What pigments are used in fresco painting?

Traditionally, fresco artists primarily used natural earth pigments that are resistant to the alkalinity of the lime plaster. These mineral-based pigments, such as various ochres, reds (like hematite), yellows (like limonite), carbon blacks, and various greens, chemically react with the drying plaster, becoming an integral part of the wall itself. Certain colors, like blues (e.g., precious ultramarine derived from lapis lazuli) and some delicate greens or yellows, were often too expensive or chemically unstable in the alkaline wet plaster, making them challenging for true buon fresco as they might react and discolour. Artists would typically reserve these for a secco additions after the plaster had dried, or employ specific, complex techniques to stabilize them, acknowledging the trade-off in long-term durability for visual vibrancy.

What was the role of patrons in fresco painting?

Patrons played an absolutely central, often defining, role in fresco painting throughout history. From ancient rulers and wealthy Roman families to the powerful Church and noble Renaissance dynasties, patrons commissioned frescoes as monumental statements. These works were not just art; they were tools to assert authority, display wealth, glorify faith, educate the populace, and cement legacies. Patrons often dictated subject matter, scale, and even the materials used, effectively shaping the artistic landscape and ensuring the creation of these enduring public works that spoke volumes about their power and beliefs.

What are the main challenges in fresco conservation?

Fresco conservation is a constant battle against time and environment. The biggest challenges include significant fluctuations in humidity and temperature, which can cause plaster to crack or pigments to crystallize. Pollution, especially in urban environments, can lead to surface degradation. Physical damage from earthquakes, human interaction, or even poorly executed past restorations also poses significant threats. Modern conservators employ advanced techniques, but the goal is always to stabilize and protect these monumental works without altering their original integrity.

What environmental conditions are most detrimental, and which aid, fresco preservation?

The most detrimental environmental conditions for frescoes include significant fluctuations in humidity and temperature, which can cause the plaster to expand and contract, leading to cracks, efflorescence (salt crystal formation), and pigment loss. High humidity encourages mold growth, while air pollution (acid rain, soot) can chemically degrade the surface. Direct sunlight can fade pigments, and seismic activity poses a constant physical threat. Conversely, stable, dry climates, protected from direct weather and with minimal human interference, are ideal for fresco preservation, allowing the natural chemical bond of buon fresco to remain intact for millennia.

What is the role of a fresco conservator?

Fresco conservators are the unsung heroes of this enduring art form. Their role is to meticulously study, preserve, and restore frescoes, often battling centuries of environmental damage, previous interventions, and the inherent fragility of the materials. This involves everything from stabilizing crumbling plaster and reattaching flaking pigments to removing layers of grime and developing protective measures against humidity and pollution. It's a highly specialized field that combines art history, chemistry, and incredible manual dexterity, all aimed at ensuring these masterpieces can continue to inspire future generations.

How does the artistic process of fresco painting differ from oil painting?

Oh, the difference is night and day! Fresco demands an incredibly fast, decisive, and irreversible approach. You're racing against the plaster drying, so there's little room for error or second-guessing. It's about broad gestures and anticipating the final chemical reaction, truly a sprint against nature. Oil painting, on the other hand, allows for leisurely layering, blending, and corrections. It offers artists immense flexibility, deep tonal range, and the ability to work over extended periods. Fresco is a thought-out, high-stakes sprint; oil painting is a reflective, patient marathon.

Are frescoes always monumental in scale?

While many of the most famous frescoes, like those in the Sistine Chapel or the Villa of the Mysteries, are indeed monumental, frescoes were also created on a smaller scale. Private chapels, tombs, and even domestic settings featured fresco decorations, though perhaps not always true buon fresco. The scale was often dictated by the patron's wealth, the importance of the message, and the size of the architectural space available, demonstrating the versatility of the technique beyond just grand public works.

Final Thoughts: Leaving Our Mark on Time

Reflecting on the history of fresco painting, I find myself not just admiring the art, but deeply respecting the sheer audacity and monumental effort of the artists who undertook such tasks. It's a profound reminder that true artistic vision often requires stepping beyond comfort zones, embracing technical challenges, and daring to create something that explicitly aims for eternity. This lineage of artists who literally fused their vision into the fabric of buildings offers a powerful inspiration. Unlike a canvas I might send off to a gallery, a fresco refuses to be moved, sold easily, or even easily separated from its context. It's a piece of history, a silent observer that has watched centuries unfold, inherently tied to its physical location. This commitment, a slow art in a fast world, is something I deeply admire and strive for in my own practice.

As an artist whose journey is marked by creating vibrant, abstract pieces, I often reflect on this. My canvases might be movable, my prints available to buy and take to new homes, but the desire to create something enduring, something that truly resonates and becomes integral to a space – whether physically or conceptually – is a shared ambition. When I visit a museum, like the one in Den Bosch, and see ancient works, I often wonder about the hands that created them, the society that commissioned them, and the stories they were meant to tell for eternity. Fresco is the ultimate storyteller, etched into the very fabric of our shared human narrative, a testament to an artist's vision against the relentless march of time. It really makes you pause, doesn't it? To consider your own creative timeline and what kind of legacy you're building, whether on a temporary canvas or a seemingly eternal wall. Perhaps, like these ancient masters, we can find ways to imbue our own creations with a sense of lasting impact, even in the ephemeral, fast-paced world of contemporary art. It connects us, generation after generation, to the enduring human desire to leave a mark, a story etched into the plaster of time, for all time. And perhaps, in my own way, with my own vibrant, abstract art, I too hope to contribute to that timeless conversation, leaving my own small, yet hopefully enduring, mark that speaks across ages.