The Enduring Flame: A Deep Dive into Encaustic Painting's Rich History & Modern Art

Uncover the captivating saga of encaustic painting, from ancient ships and lifelike Fayum portraits to Jasper Johns's impactful revival and today's vibrant abstract art. Explore its unique challenges, enduring techniques, and why this rich beeswax medium continues to inspire artists across millennia.

The Enduring Flame: Encaustic Painting's Journey Through Art History

I know, I know. "History" often conjures up images of dusty textbooks and endless dates, the kind that might have caused a good eye-roll (no judgment, I've been there!). But forget the dry facts; I'm talking about history that's alive, that breathes, that reminds us how truly brilliant ideas simply refuse to fade. For anyone drawn to the tangible, the textured, the utterly unique, the story of encaustic painting will absolutely captivate you. This ancient technique, fusing heated beeswax with pigment, has stubbornly refused to be forgotten, thriving for millennia while other art forms have come and gone. It's a profound testament to human ingenuity and the enduring power of creation—a vibrant thread connecting us to artists across the ages, revealing the shared human drive to leave a lasting mark. So, come with me on this journey, exploring encaustic's fascinating story from its ancient roots to its dynamic modern resurgence, and discover why this unique, tactile medium continues to enthrall artists and collectors today. We'll delve into its challenging past, its quiet retreat, and its fiery comeback, understanding not just what it is, but why it continues to inspire.

Ancient Origins: Where a Timeless Medium First Took Hold

So, how did this fiery medium even begin its millennia-long journey? When I first stumbled into the world of encaustic painting, its sheer antiquity truly blew my mind. We're talking ancient. Seriously ancient. Imagine artisans in Greece, around the 5th century BCE, not just creating art, but practical art—using heated wax to paint ships! They weren't just making them look pretty; they were giving them a vibrant, protective coating that truly defied the elements. Think of it: a marine-grade sealant and paint all in one, far superior to plain pitch or simple pigments that would quickly wash away or fade. The wax created an impermeable barrier, protecting the wood from saltwater and decay, giving ships a longer, more resilient life. Homer even nods to "painted warships" in the Iliad, with lines like 'Swift ships of the Achaeans, painted with pitch, sped over the wine-dark sea,' a casual mention that, to me, paints a vivid picture of these early artists as the original art-meets-engineering gurus, melding aesthetic beauty with incredible durability that was already commonplace. This tells us that even back then, people understood the power of a medium that could genuinely last.

Beyond the high seas, encaustic's remarkable versatility saw it adapted for architectural decoration, like vibrant friezes in temples, adding lasting color to stone that resisted weathering for centuries. It was also used for decorative objects like figurines, votive offerings, and even for sealing or adding permanence to early manuscripts, showing a breadth of application that always impresses me. Think about some of those intricate Greek sculptures; perhaps some of their original vibrant color, long since faded, was applied with wax. And while not strictly painting, the ancient Greeks also mastered lost-wax casting, a complex sculptural method that, like encaustic, relied on the precise manipulation of molten materials. This shared mastery of heat and material transformation—understanding how to move a substance from solid to liquid and back again with careful control—demonstrates a core ingenuity directly transferable to the careful heating of wax for painting. This ability to precisely control a material's state, turning solid into liquid and back, provided a foundational understanding of material behavior that was directly applicable to the nuanced heating and manipulation of wax for painting, laying crucial groundwork for encaustic's development.

Application | Key Characteristic / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Ships | Protective, durable, vibrant coating, anti-fouling |

| Architecture | Decorative elements, lasting color |

| Decorative Objects | Aesthetic enhancement, permanence |

| Mummy Portraits | Exceptional realism, vibrant color retention, and lifelike individuality |

But let’s be honest for a moment: achieving this was no walk in the park. Without electricity, the practical hurdles of manipulating molten wax were immense. Artists had to rely on constant, portable heat sources like braziers, hot coals, or heated metal plates to keep their wax paints – a mixture of heated beeswax and finely ground pigments – at a consistent, workable temperature. Then came the delicate task of application using heated spatulas, brushes, or styluses. Honestly, sometimes I struggle just keeping my studio tidy, let alone maintaining nuanced brushstrokes while simultaneously keeping my materials molten and avoiding accidental studio fires! Just last week, I nearly singed my eyebrows trying a new torch technique, which puts their ancient challenges into stark, humbling perspective.

And the pigments themselves? Forget ordering them online. Sourcing and preparing them was a laborious, often dangerous, process that demanded deep knowledge of geology and chemistry. Artisans would painstakingly grind natural minerals like vibrant ochres (for yellows and reds), malachite (greens), and lapis lazuli (blues) by hand, sometimes for days, to achieve the fine, consistent powder needed to mix smoothly with wax. They often used a mortar and pestle, or a muller on a grinding slab—simple, heavy tools that allowed for the painstaking reduction of raw minerals into fine powder. Once they had these precious powders, the artists would carefully heat their beeswax in braziers, then slowly incorporate the pigments, stirring meticulously to ensure an even, vibrant color. This process wasn't just about mixing; it was about truly suspending the pigment in the molten wax, a delicate balance that ensured the paint would flow smoothly and maintain its intensity. This wasn't just physical labor; it was a highly specialized craft, demanding meticulous care to prevent impurities or inconsistent particle sizes, which could ruin the paint's texture or vibrancy. Some pigments, like cinnabar, offered breathtakingly vibrant reds but contained toxic mercury, requiring extreme caution during grinding and mixing. Others, like orpiment, offered brilliant yellows but contained arsenic, making the process a hazardous, almost alchemical endeavor that truly separates these ancient creators from our modern selves. This wasn't just painting; it was a complex process of transforming raw earth into luminous, enduring art, demanding incredible skill, patience, and a healthy dose of courage.

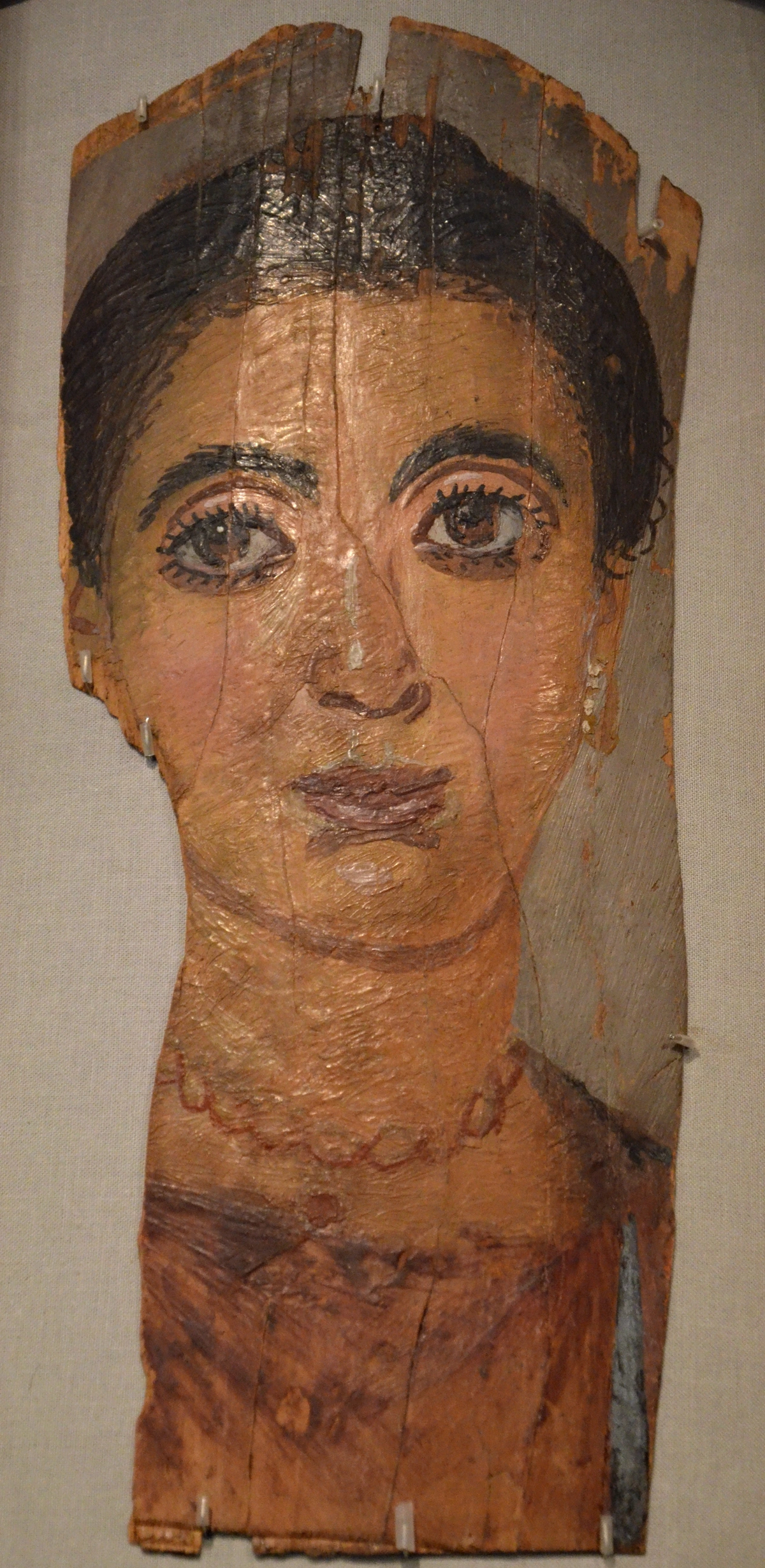

Yet, despite these daunting challenges, the results were often breathtaking and remarkably durable. The real showstopper for me, the piece that truly demonstrates encaustic's incredible staying power, is the Fayum mummy portrait from Roman Egypt. If you’ve ever seen one, you know exactly what I mean. These aren't merely pretty pictures; they are hauntingly realistic faces that gaze out at you from two millennia ago, their colors still incredibly vivid, their surfaces almost impossibly preserved. When I look into those eyes, I feel an immediate, profound connection across time, a shared humanity that transcends the ages. It’s hard to put into words, but there's a depth, a presence, that few other ancient art forms achieve.

It’s a marvel of preservation and artistry, really. These portraits, typically painted on carefully prepared rigid wooden panels—often sycamore or lime wood, prized for their stability and fine grain—were then placed over the faces of mummified bodies. The use of heated beeswax, meticulously mixed with lightfast pigments, allowed for incredible depth and luminosity, capturing individual personalities with an almost photographic quality long before cameras were even a twinkle in anyone's eye. And here's the kicker for their incredible longevity: the beeswax itself is an incredibly stable and archival material. Chemically, it's a non-oxidizing medium, meaning it doesn't break down, crack, or yellow over time from exposure to air, unlike some oil paints that can become brittle and discolored. Think of beeswax as nature's own sealant; it's naturally resistant to moisture, mold, atmospheric pollutants, and even insect damage. This intrinsic stability helps protect the embedded pigments and preserve the artwork's vibrancy for centuries, as vividly evidenced by the Fayum portraits.

Beyond these iconic portraits, some Byzantine icon painters also quietly continued to use a form of encaustic well into the early medieval period. They appreciated its luminosity and durability for sacred objects, especially in regions like monastic communities in the East (think areas of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine), which were less impacted by the Roman Empire's decline and maintained stronger links to older traditions. This shows its quiet but tenacious persistence even as other mediums took center stage. It’s a testament to the medium’s inherent qualities that it found pockets of dedicated practitioners even during its so-called 'lost' years. For a deeper dive into what this amazing medium actually is, you can check out my thoughts on what is encaustic painting.

The "Lost" Years: A Brief Retreat, Not a Vanishing Act

So, with such incredible longevity and practical applications, a question naturally arises: if encaustic yielded such breathtaking examples of durability, why did it recede from the artistic mainstream for centuries? It's a question I’ve pondered quite a bit, and my working hypothesis is this: it was just too hard. Really, truly difficult, almost impossibly so without modern conveniences. Beyond simply keeping wax molten, imagine the elaborate setups required: specialized, often primitive, heating tools; constant temperature management (a delicate dance between too hot and too cool); and the distinct, sometimes overwhelming, smell of melting wax and pigments (which, trust me, isn't always pleasant, especially in a poorly ventilated medieval workshop!). The lack of consistent, controllable heating technology and refined tools made it an incredibly demanding, labor-intensive process that simply didn't lend itself to widespread adoption. Frankly, my own patience would have been tested to its absolute limits back then – I'd probably have more melted messes than masterpieces, likely with singed eyebrows to boot! It makes me think of those frustrating days when a technical glitch completely derails my creative flow; imagine that, but every single day. I often think about how many brilliant artists simply gave up because the medium itself was too challenging, not because their vision wasn't strong.

Beyond these technical hurdles, the economic reality of the time also played a role. Beeswax was a precious commodity, and the intense labor required for pigment preparation and application made encaustic an expensive and time-consuming choice. As new patronage emerged and simpler, less costly mediums became available, the practical and financial burden simply became too great for widespread adoption. As the Roman Empire began to wane, new artistic needs and simpler techniques emerged, allowing alternative mediums to rise to prominence.

- Tempera: Often using egg yolk as a binder, tempera dried quickly and allowed for rapid execution and meticulous detail, perfectly suited for the intricate religious iconography and delicate manuscript illuminations of the medieval period. Its quick drying time meant artists could build layers faster without needing constant heat—a huge practical advantage compared to the slow, heat-dependent process of encaustic.

- Fresco: Applied directly to wet plaster, fresco became an integral part of architecture itself, offering monumental scale and a powerful, immersive experience for decorating vast church interiors and palace walls—a different kind of permanence rooted in the very structure of buildings, rather than the intrinsic stability of wax.

- Oil Painting: Later, the advent of oil painting in the Renaissance offered artists even more flexibility, with its slow drying time allowing for seamless blending, subtle gradations of color, and a luminosity that didn't require constant heat. Crucially, the increasing availability and refinement of materials like linseed oil made oil paints easier to produce and use on a wider scale. Oil paints, easier to transport and manipulate, became the preferred medium for portraiture and easel painting, further pushing encaustic to the sidelines.

These mediums were simply easier to work with, less fussy, and crucially, carried no risk of accidentally setting your masterpiece (or your studio!) on fire! While encaustic wasn't entirely forgotten – as I mentioned, some Byzantine icon painters kept a form of it alive in quieter corners, particularly in areas like monastic communities in the East, showing its quiet yet determined perseverance – it certainly receded from the mainstream art world. It's a powerful reminder of how practical and economic considerations can sometimes sideline even the most brilliant artistic techniques, at least for a spell. But then again, truly great ideas rarely stay buried for long, do they? It was only a matter of time before the flame would reignite.

A Modern Resurgence: The Fiery Comeback

But how can an art form so challenging make such a spectacular return? Great ideas, as I always say, eventually find their way back. The 18th and 19th centuries saw various attempts to revive encaustic, often spurred by a fascination with classical art and a desire to replicate its vibrant, enduring qualities. This interest surged, for instance, after archaeological discoveries like those at Pompeii and Herculaneum in the 18th century, which revealed impressively preserved ancient murals. The colors were still strikingly vivid, the textures remarkably intact—a testament to wax's preservation power that immediately captivated scholars and artists alike. However, these early revivals often struggled without the necessary technological advancements.

But it was truly in the 20th century, propelled by significant technological advances – hello, reliable electric heating tools! – that encaustic began its fiery comeback. We've come a very long way from ancient braziers and crude spatulas; modern encaustic studios can maintain precise temperatures with ease thanks to tools like heating palettes, heat guns, and even small torches. These tools allow artists to keep their wax at the optimal temperature for fluid brushstrokes, building layers, or manipulating textures. And yes, while traditional beeswax is king, some contemporary artists even experiment with synthetic waxes or wax blends, which can offer different working properties like lower melting points or increased flexibility, though they often lack the unique archival stability and natural luminosity of pure beeswax and damar. Even with these modern tools, though, working with wax still demands a certain precision and patience. You still have to manage fumes (always ensure good ventilation!), keep surfaces clean, and learn the subtle language of molten wax—it’s a constant dance, even with a heat gun in hand!

Crucially, the development of refined encaustic mediums – essentially, pure beeswax combined with a small amount of harder damar resin – has made the medium far more durable, less brittle, and significantly more accessible. Think of damar resin as encaustic's secret ingredient: this natural tree sap acts like a built-in stabilizer, making the wax harder, less brittle, raising its melting point, and adding a beautiful transparency and luminosity that enhances color depth. Compared to pure beeswax, the addition of damar creates a more robust film, reduces tackiness, and allows for greater clarity and sheen, truly refining the working properties and enhancing the overall archival quality. This refinement was a game-changer, less prone to fiery mishaps, and a major factor in its resurgence. Interestingly, the revival was also subtly aided by scientific analysis; techniques like X-ray fluorescence, used by art conservators, allowed for deeper study of ancient works, revealing the precise material compositions and encouraging modern artists to experiment with the medium's historical recipes.

Artists like Jasper Johns, in the mid-20th century, famously embraced encaustic. At a time when abstract expressionism and new synthetic paints dominated the art world, Johns's choice of encaustic was a deliberate, almost rebellious, rejection of fleeting trends. It was a statement, a return to the tactile and the enduring, and that resonates deeply with me, this idea of choosing substance over fleeting fashion. His groundbreaking work, alongside the explorations of other mid-century artists drawn to its tactile qualities, brought encaustic back into serious artistic discourse. When I look at his "Flags" or "Targets," the wax, with its inherent depth and semi-transparency, allowed him to build up intricate layers and textures. This created a sense of visual weight and physical presence that other mediums simply couldn't achieve, infusing everyday objects with an almost ancient gravitas that I find absolutely brilliant. It’s a quiet insistence that these familiar forms demand to be seen and felt.

Today, encaustic is enjoying a full-blown renaissance. Contemporary artists worldwide are exploring its immense potential, pushing its boundaries beyond traditional painting. For instance, Betsy Eby leverages encaustic's translucent layering to create abstract works that evoke natural rhythms and musicality; the ability to build depth through numerous semi-transparent wax layers allows her to craft visual symphonies of light and shadow, much like orchestral swells, inviting you to lose yourself in their shimmering complexity. Michelle Ridgway, on the other hand, masterfully employs encaustic to build incredible depth and luminosity in her figurative and landscape pieces, often embedding materials to add narrative complexity. The wax’s unique property of encasing and semi-obscuring objects allows her to weave rich, almost archaeological stories within her luminous, multi-layered surfaces, inviting viewers to discover hidden worlds, as if peering through time itself. It's truly a medium that allows for endless creative exploration.

Its unique properties truly allow for incredible versatility, offering:

- Layering and Translucency: Building up vibrant, glowing surfaces with remarkable depth. The wax can be applied in thin, translucent washes or thick, opaque layers, allowing for incredible visual interplay.

- Textural Possibilities: Carving into the wax, scraping away layers, or creating impasto effects (thick, sculptural applications of paint/wax).

- Embedding of Objects: Fusing various materials directly into the wax layers. Artists literally fuse materials like delicate rice paper, woven fabrics, dried botanicals, or even small found objects such as fading letters or maps within layers of warm wax, creating works that are both visually stunning and deeply tactile. The way the wax semi-obscures and magnifies these embedded elements creates a sense of unearthed history, a beautiful tension between what’s seen and what’s tantalizingly hidden beneath the surface.

- Malleability and Sculptural Forms: The wax's ability to be sculpted, molded, and manipulated when warm, then solidify, allows for three-dimensional forms and installations, pushing beyond the traditional flat canvas. This adds a physical weight and presence that sets it apart.

It’s messy, it’s challenging, but the results? Absolutely breathtaking; a tangible fusion of history and material. The ability to build textures, to carve into the wax, to fuse layers – it’s an incredibly versatile medium that lends itself beautifully to modern artistic visions, including sculptural forms and mixed-media installations, echoing my own journey with abstract art and mixed media.

Beyond traditional painting, artists are also pushing the boundaries by sculpting, molding, and creating three-dimensional forms directly with the molten wax, leveraging its unique adhesive and solidifying qualities. This opens up entirely new avenues for expression, moving beyond the two-dimensional surface.

The evolution of specialized heating tools, like the development of varied temperature heating palettes, has allowed for more nuanced control over the wax, enabling artists to work with different consistencies and drying times, further expanding the medium's possibilities. This constant innovation is what keeps encaustic vibrant and endlessly inspiring, proving that an ancient medium can continually reinvent itself.

A Glimpse into the Modern Encaustic Process (Conceptual Steps):

- Preparation: Artist-grade encaustic medium (beeswax and damar resin) is melted on a heated palette, along with chosen pigments. Modern pigments are lightfast (resistant to fading) and sourced from art suppliers.

- Application: Molten wax is applied to a rigid, absorbent substrate (like a wooden panel or encausticbord) using brushes, spatulas, or other tools. Flexible supports like canvas are generally unsuitable as they can lead to cracking or heat damage.

- Fusing: Each layer of wax must be "fused" with the layer beneath using a heat gun, torch, or iron. This melts and blends the layers, ensuring a strong bond and creating the medium's characteristic depth and luminosity.

- Building & Manipulating: Multiple layers are built up, often with transparent or translucent waxes for optical depth. Artists can carve into the wax, embed objects, or add texture at various stages.

- Finishing: Once cooled and cured, the surface can be buffed to a sheen or left matte. Proper care, including avoiding extreme temperatures, is essential for its longevity.

From delicate flora to powerful abstracts, encaustic truly offers a boundless canvas for artistic vision. Its inherent weight, due to the wax and rigid substrate, is also a consideration for artists and collectors when planning installation and framing.

The Encaustic Experience: A Sensory Journey and Lasting Connection

For me, the history of encaustic painting isn't just a collection of facts; it’s a profound narrative about persistence. This resonates deeply with my own creative process. I’ve hit countless walls in my studio, tried new approaches that felt like utter failures, but that core passion, that drive to create, always finds its way back. Just last month, I was wrestling with a new abstract piece, convinced it was a total disaster because a particular shadow refused to lift, leaving the texture feeling flat. It was one of those days where the wax just wouldn't do what I wanted, becoming sticky too quickly or not flowing smoothly enough. I almost threw in the towel! But something in the back of my mind, that little whisper of encaustic's enduring spirit, pushed me to try one more layer, one more fusing pass, one more scrape and reveal. And wouldn't you know it? That final effort, born from the unique properties of working with wax—the ability to add, subtract, build, and transform layers, to carve into and scrape away, to push through resistance—finally unlocked the beauty. It’s a bit like that stubborn weed that keeps popping up in my perfectly manicured (or, let's be honest, perpetually neglected) garden – nature, and art, finds a way!

This tactile engagement is central to the encaustic experience. You don't just look at encaustic art; you almost feel its history, its layers, the journey of its creation. The unique, waxy, and often subtly textured surface invites touch, creating a deeper, more intimate connection. The heat of the tools, the distinctive, honey-like aroma of beeswax melting (a scent many artists find incredibly grounding!), the subtle hiss as a heat gun works its magic, the gentle scrape of a stylus – these are all integral parts of the creative process that ground the artist in the moment and connect them to millennia of practice. It's this unique sensory engagement that draws me in every time. It drives me to create pieces that, I hope, will resonate for a long time, perhaps even inspiring someone years down the line to ponder their own connection to something enduring. It’s this deep-seated belief in lasting beauty and tactile engagement that fuels my own artistic practice.

When you're working with a medium that has such a rich, unbroken (if sometimes quiet) lineage, there’s a certain reverence that comes with it. It's more than just applying paint; it feels like holding a conversation across centuries. You're not just creating; you're participating in a legacy. It reminds you that you're part of a much larger dialogue, a long line of creators who wrestled with materials to express something profound. And because these works literally carry history within their layers, embodying the very essence of endurance and physical presence, it also makes me think about how we treat them now. Proper care for encaustic art is essential to ensure this incredible legacy continues, perhaps even for another few millennia. In terms of sustainability, encaustic can be quite an environmentally conscious choice. Beeswax is a natural, renewable resource, and many artists actively choose responsibly sourced or even recycled wax, combining it with natural, non-toxic pigments in well-ventilated studios to minimize their ecological footprint. Disposal of wax and cleaning materials typically involves allowing wax to solidify and then disposing of it as solid waste, which is generally less problematic than liquid solvents.

Key Takeaways: The Enduring Allure of Encaustic

- Ancient Roots, Modern Relevance: Encaustic is one of the oldest art forms, with a history spanning millennia, proving its enduring appeal.

- Durability and Archival Quality: Beeswax's inherent stability, combined with damar resin in modern mediums, makes encaustic exceptionally durable, resistant to moisture, and non-oxidizing.

- Sensory and Tactile Experience: The medium offers unparalleled opportunities for layering, texture, embedding, and sculptural forms, creating a unique visual and tactile journey for both artist and viewer.

- Resilience and Innovation: Despite challenges that led to its decline, technological advancements and pioneering artists brought about a powerful revival, demonstrating creativity's refusal to be bound by limitations.

- A Continuous Conversation: Working with encaustic connects artists to a lineage of creators, inviting participation in a timeless dialogue about leaving a lasting mark.

Frequently Asked Questions About Encaustic History and Practice

Q: What is "archival quality" in art, and why is encaustic considered archival?

A: "Archival quality" refers to art materials that are durable, stable, and resistant to degradation over time, ensuring the artwork's longevity. Encaustic is considered highly archival because beeswax is naturally non-oxidizing (it doesn't break down or yellow from air exposure), resistant to moisture, mold, and insects. Modern encaustic mediums also include damar resin, which further enhances durability, making the artwork stable for centuries.

Q: Where did encaustic painting originate, and what were its earliest uses?

A: Encaustic painting is believed to have originated in ancient Greece around the 5th century BCE, initially used for practical applications like painting and sealing ships. Its most famous ancient artistic application, however, comes from the incredibly preserved Fayum mummy portraits in Roman Egypt, dating from the 1st to 4th centuries CE, which demonstrate its remarkable ability to capture lifelike detail.

Q: What types of pigments are used in encaustic painting, and why are certain qualities important?

A: Historically, artists used finely ground natural mineral pigments, often laboriously and dangerously prepared by hand. Today, a wide range of artist-grade pigments, both natural and synthetic, are used. The crucial factors are that they must be lightfast (resistant to fading from light exposure) and compatible with the wax medium to prevent discoloration or degradation, ensuring the artwork's longevity and archival quality. Modern pigment sourcing is typically done through specialized art suppliers.

Q: Why did encaustic painting decline in popularity?

A: Its decline was largely due to the significant technical challenges of working with heated wax, especially before modern heating tools and electricity. The need for constant heat, specialized tools, and precise temperature control made it a demanding and labor-intensive medium. Economic factors, such as the high cost of beeswax and pigments compared to simpler, more accessible alternatives like tempera, fresco, and later, oil painting, also contributed to its retreat from mainstream art for centuries.

Q: How have encaustic tools and techniques evolved from ancient times to today?

A: Ancient artists relied on primitive, portable heat sources like braziers and heated metal plates to keep their wax molten, applying it with basic heated spatulas and styluses. Today, artists benefit from precise electric heating palettes, heat guns, and even small torches to maintain consistent temperatures and manipulate the wax with far greater control and safety. This evolution in tools has significantly broadened the medium's accessibility and artistic possibilities, making the "fusing" of layers much easier.

Q: When did encaustic painting experience a revival, and who were some key artists?

A: While some earlier attempts were made in the 18th and 19th centuries (often sparked by archaeological discoveries), encaustic painting truly experienced a significant revival in the 20th century. This was thanks to technological advancements (like reliable electric heating tools) and pioneering artists such as Jasper Johns, who explored its unique textural and layering capabilities, bringing it back into the contemporary art dialogue.

Q: Are there still contemporary artists using encaustic today?

A: Absolutely! Encaustic is enjoying a full-blown renaissance among contemporary artists worldwide. Its versatility, incredible depth, and unique tactile qualities make it a popular choice for everything from intricate portraits and evocative landscapes to expansive abstract works, mixed-media compositions, and even sculptural pieces.

Q: What is the role of damar resin in modern encaustic mediums?

A: Damar resin, a natural tree sap, is added to beeswax in modern encaustic paints. It hardens the wax, making the medium more durable, less brittle, and more resistant to scratching and cracking. It also slightly raises the melting point and adds beautiful transparency and luminosity, enhancing color depth and archival properties.

Q: What safety considerations are important when working with encaustic paint?

A: Modern encaustic practices prioritize safety. While working with heated wax, it's crucial to ensure good ventilation to dissipate fumes and to maintain wax temperatures below their smoke point (when the wax begins to smoke, indicating overheating). Artists also use appropriate safety equipment, such as gloves, and exercise caution with hot tools to prevent burns, making it a safe and enjoyable medium to work with today.

Q: What are common substrates used for encaustic painting?

A: Historically, rigid wood panels (like sycamore or lime wood) were common. Today, artists primarily use rigid, absorbent supports such as wooden panels, cradled birch plywood, or encausticbord, which provide a stable surface for the wax layers. Flexible supports like canvas are generally avoided due to the risk of cracking as the canvas flexes, and the difficulty in securely adhering wax layers.

Q: Does encaustic painting have a distinctive smell?

A: Yes, it absolutely does! Working with heated beeswax creates a unique, often pleasant, honey-like aroma in the studio. For many encaustic artists, this scent becomes part of the immersive creative experience, connecting them even further to the ancient origins of the medium. Just make sure you're working in a well-ventilated space to keep the air fresh!

The Enduring Flame: A Legacy That Continues to Burn Bright

So there you have it: a whirlwind tour through the long, often quiet, but ultimately triumphant history of encaustic painting. From the sun-baked lands of ancient Greece and Egypt to the bustling studios of contemporary artists, this medium has journeyed through time, adapting, disappearing, and reappearing with a vibrant tenacity that I find truly inspiring. It’s a story not just about paint, but about human creativity's refusal to be bound by fleeting trends or technical difficulties. It's about finding beauty in the challenge, and leaving something behind that truly lasts, physically and emotionally.

This enduring flame of creativity, carried through millennia by the resilient spirit of encaustic, serves as a powerful reminder for us all. Whether you're an artist looking for your next medium, a collector seeking a piece with deep historical resonance and a rich, tactile surface, or simply someone who appreciates beauty that defies time, I sincerely hope this journey has ignited a spark of curiosity within you. Perhaps it will even inspire you to explore encaustic art further, seek out a gallery exhibiting contemporary works, or feel a pull to try this incredible medium yourself, carrying a fragment of this timeless legacy into your own creative space. And if you're curious to see how this ancient spirit informs my own modern practice, feel free to explore my art for sale or visit my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. If you're interested in my own artistic timeline, you can always explore it here.