Art Repatriation Ethics: A Collector's Personal Journey to Cultural Justice & Stewardship

Explore the complex ethics of art repatriation through a personal lens. Understand historical injustices, diverse arguments, and practical guidelines for collectors to foster cultural justice and responsible art stewardship.

The Weight of History: My Personal Journey Through the Ethics of Repatriation in Art Collecting

You know, sometimes a topic just... sticks. It burrows itself into my thoughts during morning coffee, while I'm sketching, or even when I'm supposed to be sleeping (a common affliction for us creatives, wouldn't you agree?). The ethics of repatriation in art collecting has truly gripped me. It's not a light, airy subject like, say, the perfect shade of cerulean, but it's profoundly human, intertwined with history, identity, and, well, what it truly means to own something. This deeply personal fascination naturally led me to confront the broader, often uncomfortable, history of how so much of our global art heritage came to be where it is today. In this piece, I'll unpack the complexities of repatriation, exploring its historical roots, ethical dilemmas, and what it means for us as art lovers and collectors, trying to navigate the chaotic beauty of it all.

I've always been drawn to the stories behind objects. As an artist, I pour my own narrative into my work, but with older pieces, especially those of cultural significance, the narratives become vast, stretching back centuries. They often involve power imbalances and historical injustices that, to be honest, leave my artistic brain a bit overwhelmed, trying to reconcile beauty with buried pain. It's a bit like trying to capture the entire ocean in a single brushstroke, or maybe like an abstract piece where each new layer of meaning, while adding depth, also somehow obscures the original truth. This isn't just about owning a beautiful object; it's about its soul, its journey, and who truly holds the key to its story. My own collection? Well, let's just say I've had to do some serious soul-searching about some of the curiosities I've picked up over the years, making sure they don't carry their own unspoken burdens.

The Echoes of the Past: How We Got Here

My personal reflections on ownership and history naturally lead us to the broader, often uncomfortable, reality of how much of what we now consider "cultural heritage" in major Western museums and private collections actually got there. Let's be honest, their acquisition often involved circumstances far from ideal. Colonialism, trade routes fueled by undeniable power imbalances, and archaeological digs that, looking back, frequently felt more like outright plunder – these are the stark, uncomfortable truths we, as collectors and art lovers, absolutely need to confront. The evolving field of archaeological ethics, for instance, now rigorously questions past excavation practices, shifting from mere extraction to a focus on preservation in situ and collaboration with source communities.

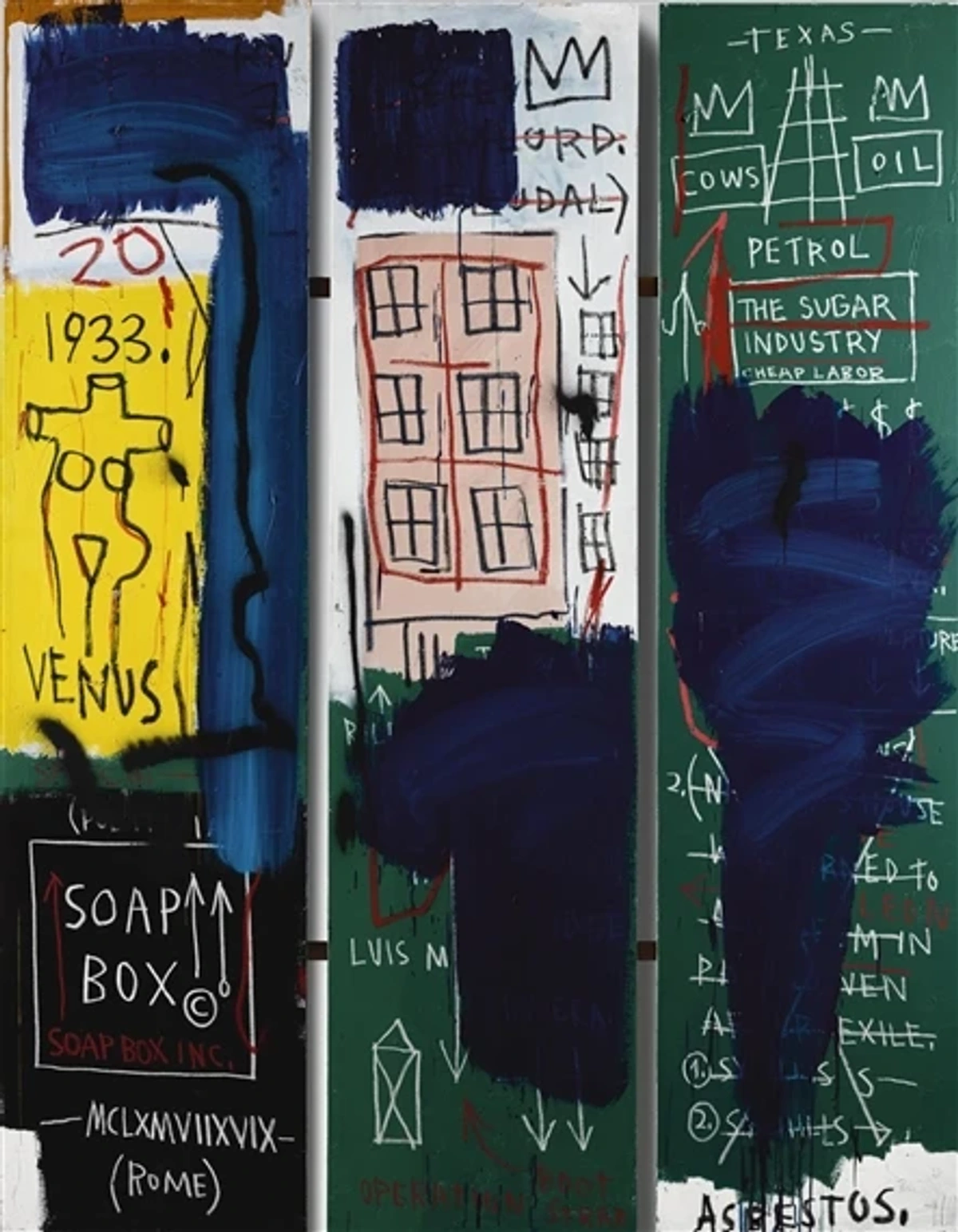

Think of iconic examples like the Parthenon Sculptures (often referred to as the Elgin Marbles) in the British Museum, where Lord Elgin removed them from the Acropolis under questionable Ottoman authority; the Benin Bronzes, many looted during the 1897 British punitive expedition known as the Sack of Benin City; the Rosetta Stone, transferred to British hands after Napoleon's defeat in Egypt; or the Bust of Nefertiti in Berlin, acquired under circumstances that are still debated regarding its export legality. These aren't just names; they represent the raw historical wounds of events where thousands of priceless artifacts were violently seized or acquired under duress.

It’s like finding dusty, forgotten ledgers in the attic of a charming old house, revealing a truly unsavoury past you now must contend with. This isn't a new conversation, of course. Experts have been grappling with the ethics of art collecting for decades, trying to untangle centuries of intertwined histories. International bodies like UNESCO have long been involved in developing ethical guidelines and conventions for the protection and return of cultural property. It’s also worth noting the historical role of private collectors, whose early motivations often differed. While some were driven by genuine curiosity and a desire to build personal 'cabinets of curiosities' (a practice dating back to the Renaissance), others, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, actively participated in the burgeoning art market, often acquiring pieces through agents operating in colonial contexts. Figures like Joseph Duveen became legendary for supplying wealthy American industrialists with European masterpieces, and this demand, coupled with the often vague or non-existent export laws of the time, undeniably fueled the flow of cultural objects into Western hands, sometimes through less than scrupulous means. For me, it boils down to acknowledging that many cultural objects aren't just art; they are living testaments to identity, spirituality, and community. Imagine a piece of your family history, something deeply personal, suddenly adorning someone else's mantelpiece across the globe, with its true significance potentially lost or misinterpreted. It hurts, doesn't it? It just feels… wrong. And this feeling of 'wrongness' is precisely what fuels the ongoing discussion around repatriation.

Repatriation: More Than Just Shipping Art Back

So, what exactly are we talking about when we say "repatriation"? At its core, it's the return of cultural property to its country or community of origin. But it’s rarely as simple as packing a box and slapping on a shipping label. It involves complex legal, ethical, and logistical considerations that feel a bit like trying to unravel a particularly tangled knot of yarn. Think of it less as a simple transaction and more as a profound act of reconciliation, a chance to mend historical wounds that still ache in the present. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) also provides ethical codes that guide institutions in these complex decisions. Crucially, the definition of what constitutes 'cultural property' and its significance is increasingly being shaped by indigenous knowledge systems and community-led initiatives. It's not just about Western legal frameworks; it's about respecting the deep spiritual and ancestral connections source communities hold with these objects. (Though, I sometimes wonder, what happens when those source communities have been dispersed, or their traditions fragmented by centuries of upheaval? It’s another tangled thread in this complex weave, isn't it?)

Then there's restitution, a term often used interchangeably but with a slightly narrower, yet equally crucial, meaning. Restitution specifically refers to the return of property acquired illegally or immorally. Repatriation, on the other hand, is a broader term, encompassing moral obligations even if the initial acquisition wasn't strictly illegal at the time, but is profoundly ethically problematic by today's standards. It's about recognizing that what was deemed 'legal' by the prevailing powers centuries ago might now be seen as deeply unjust – like a legal contract signed under duress, where the spirit of justice was entirely absent. This requires us to really dig deep into the ethical considerations when buying cultural art.

It's also worth briefly noting the concept of cultural patrimony. While cultural property often refers to specific objects, cultural patrimony is a broader, sometimes legal, concept encompassing the entire body of cultural heritage, including intangible elements (like languages, traditions, knowledge systems), considered inalienable to a people or nation. It often implies a collective, inherent right to that heritage, making its return not just about an object, but about affirming a people's enduring connection to their past and future. Think of it as the difference between a single ancient vase (cultural property) and the entire archaeological site, its surrounding traditions, and the stories passed down through generations about that site (cultural patrimony). It's the difference between owning a brushstroke and understanding the entire abstract movement it belongs to. Ultimately, whether we call it repatriation or restitution, the aim is to acknowledge history and re-establish a connection that was, at some point, unjustly severed – a vital distinction for us, as collectors, to grasp.

Feature | Repatriation | Restitution |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Broader: Moral, cultural, or historical reasons | Narrower: Specifically for illegal or immoral acquisition |

| Basis | Ethical obligations, cultural significance, historical justice | Legal or moral wrongdoings, historical context of theft |

| Legality | Can apply even if original acquisition was "legal" at the time | Primarily for objects taken in violation of existing laws/ethics at time of acquisition |

| Goal | Reconciliation, cultural healing, recontextualization | Rectifying a specific, identifiable injustice |

The Heart of the Matter: Why It's So Contentious (And My Own Wobbly Opinions)

This is where my internal monologue gets really lively, a swirling vortex of thoughts much like the early stages of an abstract painting – chaotic, yet full of potential meaning. On one hand, the arguments for repatriation resonate deeply with my sense of justice:

- Cultural Identity and Healing: For many communities, these objects are not mere artifacts but vital, pulsating links to their ancestors, spiritual beliefs, and ongoing cultural practices. Their return can be a profoundly powerful act of healing and reaffirmation of identity, mending a spiritual fabric torn by history.

- Historical Justice: At its simplest, it's about rectifying past wrongs. Plain and simple. It's a tangible acknowledgement of the immense power imbalances and often violent, exploitative circumstances of acquisition.

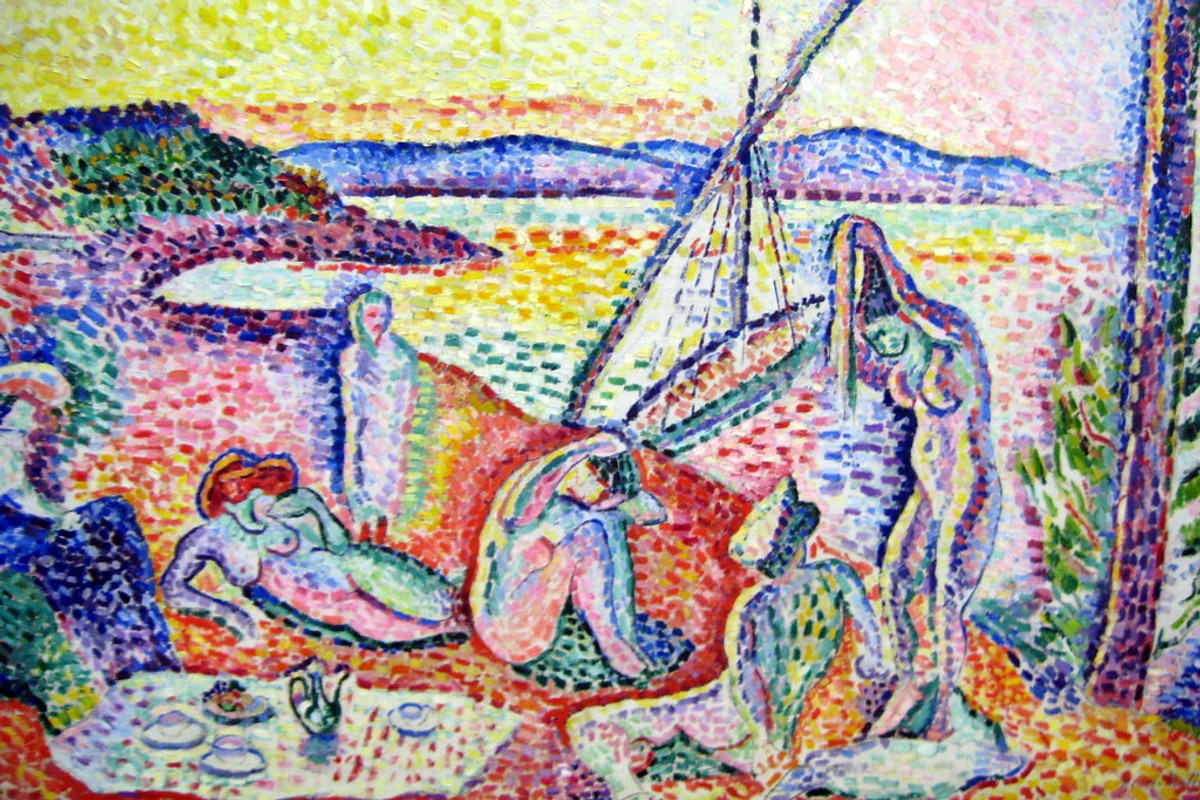

- Recontextualization: An object truly comes alive, vibrates with its original energy, when it's viewed within its intended cultural context. Seeing a sacred mask in a vibrant community ceremony is profoundly, fundamentally different from seeing it behind temperature-controlled glass in a silent European museum.

But then, the pragmatist (or perhaps, the slightly anxious hoarder in me, always a bit wary of letting go) pipes up with the counter-arguments, which, to be fair, also hold considerable weight:

- Universal Heritage: Some major encyclopedic museums and their proponents genuinely argue that great art and cultural objects, by their sheer beauty and historical significance, transcend national boundaries and belong to all of humanity. This view often suggests that these institutions, with their vast resources, specialized conservation expertise, and global reach, are uniquely equipped to preserve these treasures, conduct scholarly research, and make them accessible to a worldwide audience for comparative study. It also posits that in some historical cases, removal, though ethically problematic, inadvertently led to the preservation of items that might have been lost or destroyed in their original context. (And here's another thought that nudges at my artistic brain: what about objects that were originally created for trade, or as diplomatic gifts between cultures, where the initial intent wasn't exclusive ownership but broad circulation? Does "universal heritage" apply differently then?) However, a significant counter-argument strongly asserts that an object's deepest meaning is intrinsically tied to its people and place of origin. For many, the original context and cultural significance to the source community far outweigh the benefits of broad accessibility in these often decontextualizing museums, where the very act of removal strips them of their sacred or functional meaning. It's a bit like believing the perfect note can exist anywhere, when sometimes, like a specific bird call, it only truly sings and makes sense in its original, vibrant ecosystem.

- Conservation and Resources: This is a truly valid concern. Are the originating countries always equipped with the specialized resources, the precise climate control, and the deep expertise required to properly preserve these often delicate, ancient artifacts? This is not a dismissible question. However, this challenge is increasingly being addressed through international collaboration, significant funding for capacity building initiatives (e.g., training local conservators in modern techniques, investing in climate-controlled storage facilities, and developing robust museum management expertise), and shared expertise. Many originating countries now possess world-class conservation facilities and trained professionals, turning what once seemed an insurmountable barrier into an opportunity for partnership and mutual growth. (Though, I sometimes muse, aren't there also powerful, time-tested traditional conservation methods, passed down through generations, that are just as valid and perhaps even more culturally appropriate than Western scientific approaches? It’s a broader conversation about what "properly preserve" truly means.)

- Precedent and the Emptying of Museums: Ah, the classic "slippery slope" argument – the fear that if we return one object, a domino effect will ensue, leading to major museums being stripped bare of their most prized possessions. The image of the British Museum or the Louvre standing empty, while undeniably provocative and a powerful mental image, is often exaggerated. (Though, a tiny, almost imperceptible part of me does wince at the thought, I'll admit). I suspect the answer is far more nuanced than this, focusing on specific, well-researched cases with clear ethical claims, rather than a blanket approach. Notably, the 2018 agreement for the return of the 'Mali-Mali' ceremonial shield to Australia by the Peabody Essex Museum serves as a powerful example of successful negotiation without triggering widespread emptying, demonstrating that thoughtful, case-by-case repatriation is achievable and not a doomsday scenario. Furthermore, concepts like cultural exchange and long-term loans are emerging as creative alternatives that allow for objects to be shared and studied globally without relinquishing ownership, fostering dialogue rather than division.

- Accessibility: For many global citizens, a trip to the British Museum or the Louvre is indeed far more feasible than visiting a remote village or a newly established museum in another country. But here's my wobbly opinion: is ease of access always the primary ethical consideration? I don't think so. The intrinsic value, spiritual significance, and rightful ownership by a community often hold a weight that transcends mere convenience for a global tourist.

It’s a perpetual balancing act, isn't it? A bit like trying to find that perfect sweet spot between spontaneity and structure in an abstract painting – you want both, but they often pull in wildly different directions.

The Collector's Compass: Navigating the Ethical Waters

So, after wading through all these complex ideas – a mental workout akin to trying to simultaneously listen to five different symphonies – what does this actually mean for you and me, the art lovers and collectors who simply want to engage with art ethically? We might not be dealing with ancient Benin Bronzes every day, but the principles of ethical collecting apply across the board. How do we, as individuals who love art, navigate these waters without inadvertently causing more ripples? (And yes, I too have felt the magnetic pull of a 'just-one-more' curious artifact in an antique shop, only to snap back to reality and demand its full history.) Here’s my evolving compass, particularly for private collectors:

- Provenance, Provenance, Provenance: This truly is your North Star, the single most critical guide. Knowing an artwork's full history – its entire journey from creation to potentially your wall – is paramount. My previous articles on understanding art provenance and the role of provenance in collecting high-value abstract art delve much deeper into this essential practice. If a piece has a murky past, if its origins are vague, questionable, or outright untraceable, a red flag should immediately go up. It’s always better to walk away than to unwittingly contribute to a problematic chain, no matter how tempting the piece.

- Ask the Hard Questions: Don't be afraid to inquire rigorously about the acquisition history of a piece, especially if it's cultural, ancient, or has significant historical context. A truly reputable dealer or gallery should not only be transparent but welcome such questions, providing clear, documented answers. If they hesitate, that's another red flag waving in the breeze.

- Research the Ethics of Dealers and Galleries: It's not just about the art's provenance; it's about the provenance of your dealer. Take the time to research the ethical practices and reputation of the galleries and dealers you work with. Are they known for transparency? Do they actively support fair trade and ethical sourcing? Your choice of vendor is as much an ethical statement as your choice of art.

- Support Contemporary Artists from Indigenous Cultures (as a Direct Alternative): Instead of seeking out potentially looted historical artifacts with ambiguous pasts, why not redirect your passion and investment? Support living artists who are actively creating and sharing their culture today. This not only directly benefits communities and fosters vibrant, ethical art ecosystems, but it also helps prevent future historical injustices by ensuring cultural narratives are told by those who own them. I often reflect on the enduring influence of Indigenous art on modern abstract movements and find immense inspiration there, a clear path for positive impact.

- Understand and Respect Cultural Protocols: Building on supporting contemporary Indigenous artists, it’s not enough to simply buy the art; you must educate yourself on the specific cultural protocols associated with its creation, display, and ownership within the artist's community. This could mean understanding taboos around public display, specific care instructions, or even the narrative a piece is meant to convey. Ignoring these protocols, however unintentional, can be deeply disrespectful. It's about buying into a relationship, not just a transaction.

- From Ownership to Stewardship (and Potential Return): This is a crucial mental shift for me. Perhaps we need to move beyond the traditional concept of absolute ownership – the idea that 'I bought it, it's mine to do with as I please' – to one of mindful stewardship. We are, after all, temporary custodians of beauty and culture. Our role is to protect, appreciate, learn from, and if necessary, facilitate the respectful return of pieces that truly belong elsewhere, back to their communities of origin. This is something I think about often, even with my own artistic timeline – each piece a moment in time, a shared experience that I'm merely guiding through the world.

Looking to the Horizon: A Path Forward (Hopefully)

The future of repatriation isn't, and shouldn't be, about emptying museums overnight or shaming collectors into hiding their acquisitions. For me, it's about honest dialogue, genuine collaboration, and the painstaking process of finding nuanced, equitable solutions. It’s about building bridges, not just drawing lines in the sand. My experience at my own museum in 's-Hertogenbosch reminds me that institutions are increasingly aware of these complex issues and actively seeking ethical paths forward. The journey ahead, like the endless layers of an abstract work where each stroke contributes to a fuller picture, will require collective effort. What exactly does this path look like?

Fostering Dialogue & Research

- Open Communication & Active Listening: This is foundational. Museums, communities of origin, and governments absolutely need to talk – and critically, they need to actively listen to one another, understanding different perspectives and acknowledging historical traumas. It’s a bit like trying to explain quantum physics to a cat – fascinating in theory, but the practical application can feel… elusive.

- Thorough Research and Transparency: Meticulously researching the history of collections, documenting provenance with care, and making that information publicly available is a crucial first step. Hiding information only fuels suspicion. However, it's also important to acknowledge the significant challenges in proving ownership or historical injustice for very old artifacts where documentation is scarce or lost to time. This often requires interdisciplinary research and respectful engagement with oral histories and community memory, which can fill crucial gaps where written documentation is scarce or non-existent.

- The Expertise of Scholars: Art historians and anthropologists, with their deep understanding of cultural contexts and historical movements, play an increasingly vital role in mediating these discussions, providing crucial research and expertise. They help to illuminate the intricate narratives woven into these objects.

Frameworks for Action

- Role of International Law and Conventions: We must acknowledge the growing framework of international law and conventions, such as those established by UNESCO and UNIDROIT, which provide ethical guidelines and legal mechanisms for the return of cultural property. These aren't perfect, but they offer a vital starting point for global consensus and increasing scrutiny in the private art market.

- Partnerships & Capacity Building: Working together on conservation efforts, developing joint exhibitions, and fostering cultural exchange can build incredible bridges. This also includes capacity building, where established institutions assist originating countries in developing their own infrastructure and expertise for preservation and display, turning a perceived obstacle into an opportunity for growth and genuine shared responsibility.

Navigating Nuances

- Addressing 'Original' Cultural Context: This is a tricky one, and something I often ponder. For objects that have been part of multiple cultural exchanges over centuries, whose precise origins are lost to antiquity, or that were originally created for trade, identifying a singular "original" cultural context can be incredibly challenging. For instance, consider a ceramic vessel from the ancient Silk Road, showing motifs from both Central Asia and China, or a mask from a multi-ethnic region with evolving ritualistic uses, or perhaps even pre-Columbian gold that traversed vast ancient trade networks—pinpointing a sole 'original' context for repatriation becomes a complex archaeological and ethical puzzle. Acknowledging this complexity is key to finding respectful and nuanced solutions.

- Digital Archiving and Virtual Access: While offering unparalleled access globally, digital archiving and creating comprehensive virtual access to collections cannot fully replicate the tactile, spiritual, or communal experience of an object in its original context. Nonetheless, it serves as a powerful complementary solution, democratizing access for scholarly study and public appreciation.

- Ethical Considerations for Displaying Repatriated Objects: The return of objects is just one step. Communities of origin face their own ethical considerations regarding the display of repatriated items. This includes ensuring they are accessible to their rightful communities, interpreted authentically according to indigenous knowledge systems (perhaps guided by elders or traditional storytellers), and conserved in a way that respects both traditional practices and modern preservation needs. It’s about more than just a physical return; it’s about cultural re-integration and empowering communities to tell their own stories.

The Broader Ethical Landscape

- Education: We, as art lovers, collectors, and citizens of the world, need to educate ourselves continuously. The more we understand the historical context, the ethical dimensions, and the ongoing debates, the better equipped we are to make responsible choices and advocate for justice.

- Considering Cultural Appropriation: While repatriation focuses on ownership and return, it's worth briefly acknowledging the related concept of cultural appropriation. This is the adoption or use of elements of a minority or marginalized culture by a dominant culture, often without understanding, respect, or permission. It highlights the broader sensitivity required when engaging with cultural expressions that are not our own, reinforcing the need for genuine respect and ethical engagement in all artistic interactions.

This path forward is long and winding, much like a long abstract painting that reveals its true meaning only after many layers. But it's a path we must walk together.

My Journey Continues: A Call to Thought

As I wrap up this rather intense internal monologue – a bit like finishing a particularly challenging, layered painting – I realize there are truly no easy answers, no simple checkboxes to tick. The ethics of repatriation are a complex tapestry woven with myriad threads of history, justice, cultural identity, and profound power dynamics. It's a conversation that requires immense patience, deep empathy, and above all, a genuine willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, even when they challenge our long-held assumptions.

For me, it’s a constant, visceral reminder that art, in all its forms, carries immense weight – a weight that is both beautiful and burdensome. It’s not just paint on canvas or clay molded by hands; it’s a living piece of humanity’s story, imbued with spirit and memory. And ensuring that story is told truthfully, respectfully, and by those to whom it truly belongs, is perhaps the most profound act of appreciation, the most resonant stroke of justice, we can possibly offer. It’s a messy, beautiful, ongoing journey, and I’m just trying to navigate it with open eyes and a thoughtful brush, one conscious decision at a time, hoping to paint a clearer picture of an ethical future for art. I invite you to join this ongoing conversation, to ask hard questions, and to approach the world of art with both passion and a profound sense of responsibility.

Frequently Asked Questions About Repatriation and Art Collecting

What exactly is cultural heritage?

Cultural heritage refers to the legacy of physical artifacts (like artworks, historical documents, buildings) and intangible attributes (traditions, languages, knowledge systems, natural landscapes) of a group or society. It’s what we inherit from past generations, maintain in the present, and are entrusted to pass on for the benefit of future generations.

Why has repatriation become such a significant issue in recent years?

Repatriation has gained significant prominence due to a growing global awareness of colonial legacies, historical injustices, and the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples and source communities to reclaim their cultural property. Evolving international conventions (like those from UNESCO and UNIDROIT) and changing ethical standards in the art world also play a major role in this heightened focus, pushing for greater transparency and accountability from both institutions and private collectors.

What's the difference between restitution and repatriation?

While often used interchangeably, these terms have distinct nuances. Restitution specifically refers to the return of cultural objects that were acquired illegally or immorally, often under duress or theft. Repatriation is a broader term that encompasses restitution but also includes the return of objects for moral, cultural, or spiritual reasons, even if their initial acquisition was not strictly illegal by the laws of the time, but is deemed ethically problematic by contemporary standards.

Can I still collect cultural art ethically?

Yes, absolutely! The key lies in diligent research and ethical sourcing. Focus primarily on contemporary art from living artists, especially those from Indigenous communities, purchased directly or through reputable channels that transparently benefit the artists. For older cultural art, provenance (the complete history of ownership) is paramount. Avoid pieces with unclear, vague, or suspicious origins. Crucially, when acquiring contemporary Indigenous art, it's vital to understand and respect the cultural protocols associated with its creation, display, and ownership. Consider the intent behind your acquisition: is it for genuine appreciation and cultural exchange, or for status, speculation, or exploitation?

What if an object's origins are genuinely unclear or untraceable?

When an object's provenance is genuinely unclear or untraceable, it raises significant ethical concerns. In such cases, the most responsible approach for private collectors is often to err on the side of caution and avoid acquisition entirely. For institutions, this can trigger intensive research to uncover its history, sometimes leading to collaborations with source communities and interdisciplinary scholars to shed light on its past. Ultimately, when faced with persistent ambiguity, the ethical compass often points towards prioritizing the potential cultural and historical rights of source communities over an individual's desire for ownership.

What are the ethical considerations for displaying repatriated objects?

The return of objects is just one step. Communities of origin face their own ethical considerations regarding the display of repatriated items. This includes ensuring they are accessible to their rightful communities, interpreted authentically according to indigenous knowledge systems, and conserved in a way that respects both traditional practices and modern preservation needs. It’s about more than just a physical return; it’s about cultural re-integration and empowering communities to tell their own stories.

How can collectors contribute positively to this conversation?

Collectors can make a substantial positive impact by:

- Practicing rigorous and transparent provenance research for any acquisition.

- Prioritizing and financially supporting contemporary artists, particularly those from diverse cultural backgrounds, ensuring direct benefit.

- Engaging in open, respectful dialogue with dealers, institutions, and source communities, advocating for ethical best practices.

- Shifting their mindset from absolute ownership to one of long-term stewardship of their collection.

- Actively advocating for ethical practices and greater transparency within the art market as a whole (e.g., supporting organizations dedicated to provenance research or cultural heritage protection).

What is the ethical responsibility of private collectors regarding potentially repatriated items?

Private collectors bear a significant ethical responsibility, particularly when an item in their collection is identified as potentially subject to repatriation claims. This involves proactive provenance research, engaging transparently with source communities or their representatives if a claim arises, and being prepared to consider voluntary return or participate in mediated discussions. It also means educating oneself on international conventions and ethical guidelines, and ensuring new acquisitions are thoroughly vetted for ethical sourcing to prevent contributing to further historical injustices. Shifting from absolute ownership to stewardship is key here.

What role does international law play in repatriation claims, and what are the challenges?

International law and conventions, such as those by UNESCO (e.g., the 1970 Convention on the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property) and UNIDROIT (e.g., the 1995 Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects), provide a crucial framework. They establish ethical guidelines, legal mechanisms, and foster international cooperation. However, challenges include the non-retroactivity of some conventions (not applying to past acquisitions), differing national laws, difficulties in proving ownership or illegal export for very old artifacts, and the absence of a universal enforcement body. This often necessitates complex negotiations and relies on the good faith and ethical commitment of institutions and collectors.

How does cultural appropriation relate to repatriation?

While repatriation focuses on the physical return of cultural property to its origin, cultural appropriation refers to the adoption or use of elements of a minority or marginalized culture by a dominant culture, often without understanding, respect, or permission. The two are related as both involve questions of ownership, respect, and power dynamics concerning cultural expressions. Ethical engagement in art collecting, particularly for contemporary Indigenous art, requires not only careful provenance but also a deep understanding and avoidance of cultural appropriation, ensuring that cultural narratives are honored and shared respectfully by their rightful creators and communities.