The Unseen Link: How Japanese Calligraphy Profoundly Shaped Abstract Expressionism: A Personal Journey

Sometimes, the most profound connections in art aren't immediately obvious. They're like whispers across continents, or echoes in a gallery you only hear if you're truly listening. As an artist, diving into the history of art, it's these hidden threads that truly captivate me. And few are as fascinating, or as personally resonant, as the enduring influence of Japanese calligraphy on the raw, explosive energy of Abstract Expressionism. It’s a bit like discovering that the wild, spontaneous dance you admire actually has roots in a highly disciplined, ancient ritual – a beautiful paradox, wouldn't you agree? This journey into the unseen, this quiet conversation between East and West, continues to shape modern artistic thought, much like the subtle yet profound shifts in my own creative process where letting go of control often yields the most authentic results. In this article, we'll explore the meditative discipline of Shodō, the explosive energy of Abstract Expressionism, and the surprising ways their philosophies and techniques converged to leave an indelible mark on the canvas of art history.

My own artistic journey, documented in my timeline, often grapples with similar ideas of internal landscapes and spontaneous expression. The quest for authentic expression, whether through a vibrant print or a large-scale painting you might find for sale, is a continuous dialogue between control and release. This exploration into the roots of abstract art helps me understand the deeper currents that flow through my own pieces, sometimes even those exhibited at the museum in 's-Hertogenbosch.

Shodō: The Art of the Unhesitating Stroke

Before we jump into the vibrant world of mid-20th-century New York, let's take a moment to appreciate the source of this quiet revolution: Japanese calligraphy, or Shodō. Now, if you're like I once was, you might think of calligraphy simply as elegant handwriting. But in Japan, Shodō is so much more. It's a meditative practice, a martial art of the brush, a philosophical statement. It's about capturing the essence of a moment, a thought, or a feeling with a single, unhesitating stroke. There's no going back, no erasing. Just pure, unadulterated presence. This commitment to the now, this absolute embrace of the irreversible gesture, feels incredibly familiar to anyone who’s ever wrestled with a blank canvas, hoping for a spontaneous breakthrough. It's that fleeting moment where thought dissolves, and pure action takes over – a true testament to the power of gestural abstraction.

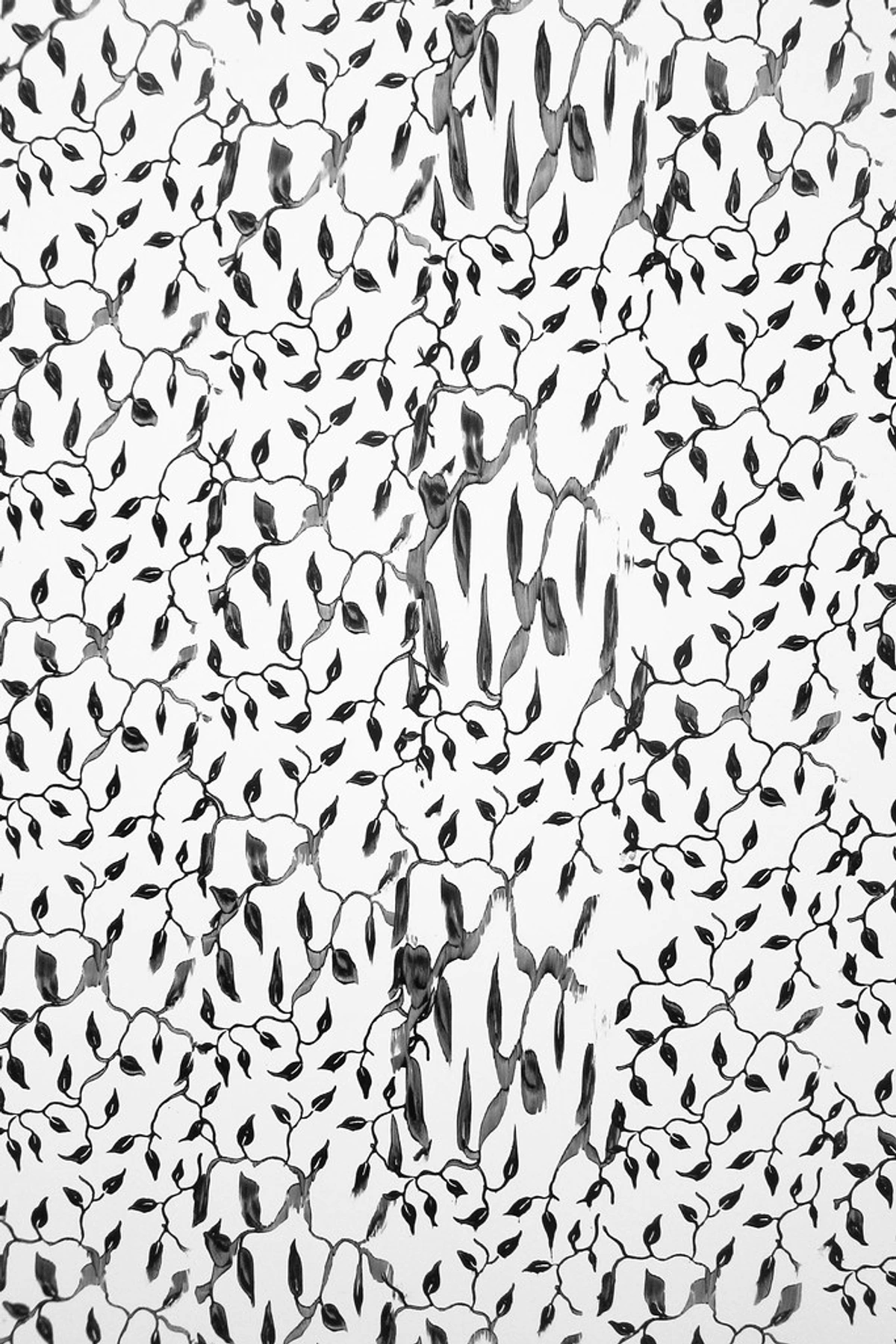

Imagine the artist, poised, breath held, then moving with an almost violent grace, ink flying, creating a character that is both perfectly formed and wildly expressive. This isn't just about legibility; it's about spirit, about the chi (life force or vital energy) infused into the brushstroke – a concept vital to both the artist and the artwork. Shodō masters focus intently on the physical act: the precise pressure of the brush (hitsu-i), the varying viscosity of the ink (bokuju), and the controlled creation of dry brush streaks (kasure) or subtle ink bleeds (nijimi). Each element is intentional, yet born from spontaneity. These techniques aren't mere accidents; kasure creates a dynamic, textured line that conveys speed and energetic movement, much like the raw, visible brushstrokes in Abstract Expressionism, while nijimi allows for subtle, ethereal gradations and a sense of depth, as if the ink is breathing, echoing the nuanced washes found in some abstract works. The preparation of materials itself, from grinding the ink on a suzuri (inkstone) to the precise loading of the brush, is part of this meditative process, an act of mindful presence before the spontaneous outburst. It's this deep connection to the materials, their textures and behaviors, that I find myself returning to again and again in my own studio, trying to coax out a similar sense of living energy.

The famed Zen circle, Ensō, is a perfect example – a single, continuous brushstroke meant to express a moment when the mind is free to let the body create. It speaks of emptiness, fullness, and the infinite all at once. This dedication to the process of creation, to the mindful act, forms the bedrock of its enduring appeal, deeply rooted in Zen Buddhist principles of direct experience and intuitive understanding. It also embodies wabi-sabi, finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence, as each stroke is unique and unrepeatable. I sometimes try to bring this level of focus to my own abstract pieces, though I'm usually just hoping I don't spill paint on my good trousers! This deep engagement with the present moment and the raw materials laid the philosophical groundwork for movements that would emerge continents away.

The materials themselves contribute to this spiritual connection. The animal hair brush becomes an extension of the body, a living conduit for expression. The sumi ink, often ground by hand on a suzuri, is a living substance whose viscosity can be precisely controlled, creating infinite nuances of black and grey. And the washi paper, with its absorbent texture, is a responsive surface that captures every nuance of the brushstroke, from the sharpest line to the softest bleed. This intimate relationship with materials is something that resonates deeply with my own creative philosophy, recognizing the inherent qualities each medium brings to the art. The dance between artist, brush, ink, and paper is a conversation, a negotiation where each element has a voice. It's a reminder that even in my wildest pours, the paint itself has a say in the final composition.

Abstract Expressionism: The Canvas as Arena

Now, let's shift our focus across the Pacific to a different kind of artistic revolution that was brewing in post-war America. After the devastation of World War II, a new, radical art movement erupted in America, particularly New York. This was Abstract Expressionism, a movement defined by raw emotion, grand scale, and a powerful rejection of traditional forms. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and Joan Mitchell weren't just painting pictures; they were enacting dramas on canvas. They were searching for a new visual language to express the anxieties, hopes, and profound shifts of their time – a time often marked by existential uncertainty and a search for authentic meaning in a shattered world. The world had seen enough, perhaps, of literal depiction; it was time for art that spoke directly to the soul's turmoil and resilience. It was about confronting the void, not by illustrating it, but by feeling it on a monumental scale.

I remember first encountering a huge Pollock at a museum. My initial thought was, "Is this just splatters? Did he just... throw paint?" But the more I looked, the more I felt the energy, the intentionality behind the apparent chaos. It wasn't about depicting something; it was about being something. It was about the act of painting itself, the physicality, the trace of the artist's body and mind. It was a search for authentic expression, an almost primal scream on canvas, a direct link from the artist's psyche to the material. If you want to dive deeper into this fascinating period, check out our ultimate guide to Abstract Expressionism.

The Meeting Point: Where East and West Converged in Gesture

So, how did these two seemingly disparate worlds – ancient Japanese discipline and post-war American spontaneity – connect? It wasn't through a direct, master-apprentice relationship. It was a profound cultural osmosis, a fascinating exchange of ideas that intensified after the war. Think of it as a shared consciousness emerging across continents, a deep, unseen current flowing through the artistic landscape, much like how a dream from last night might unexpectedly color your entire day. This unique confluence ultimately laid the groundwork for a new chapter in the history of abstract art.

A Shifting Post-War Landscape: Why America Looked East

After the cataclysm of World War II, the Western world, particularly America, grappled with profound existential questions. Traditional structures and belief systems seemed shattered, prompting a search for new meaning and authentic experience. European artistic dominance also waned, opening a space for American artists to forge their own identity. In this climate of introspection and a desire for liberation from artistic conventions, Eastern philosophies, particularly Zen Buddhism, offered compelling answers. They emphasized direct experience, intuition over intellect, and a non-dualistic view of self and world – ideas that resonated deeply with artists seeking to express raw emotion and individual truth through abstraction. Beyond Zen, the broader principles of Taoism, with its emphasis on naturalness, spontaneity, and the harmony of opposites, also found subtle resonance, contributing to a philosophical receptiveness that paved the way for the powerful influence of Japanese aesthetics and thought.

Visual Dialogue: Exhibitions, Gutai, and Pre-existing Influences

Before diving deeper into philosophy, it's crucial to acknowledge the visual channels of influence. Exhibitions of Japanese calligraphy, sumi-e painting, and other East Asian arts became more frequent in the U.S. in the post-war period, notably at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Asia Society. These showcases provided direct visual evidence of a powerful gestural tradition. Publications such as Art International showcased the dynamic brushwork of artists from the avant-garde Gutai group from Japan, who shared Abstract Expressionism's radical spirit. This visual exposure provided a powerful, undeniable parallel. The Gutai group, in particular, was truly pioneering; their performance art, where artists would create by breaking through paper screens or wrestling with mud, embodied a direct, physical engagement with materials that mirrored the action painters' visceral approach. Take, for instance, Kazuo Shiraga's "Challenging Mud" (1955), where he literally wrestled in a pile of mud, creating art through the raw impression of his body – a powerful, almost primal act of spontaneous creation that resonates with the physical intensity of Pollock's drips. It’s hard not to see the echoes of Pollock's drips in their actions, even if the influence was more atmospheric than direct. You can read more about their impact in our article on the legacy of Gutai: Japan's radical post-war art movement.

Beyond Gutai, the broader influence of Japanese aesthetics, including ukiyo-e woodblock prints, had already seeped into Western art for decades, paving the way for a deeper appreciation of East Asian visual culture. Ukiyo-e, with its bold outlines, flattened perspectives, and often asymmetrical compositions, had already informed artists from Impressionists to Post-Impressionists, sensitizing Western eyes to different ways of seeing and composing. This pre-existing cultural dialogue made the reception of calligraphic principles even more impactful; the ground was already fertile.

Philosophical Currents: Zen, Existentialism, and the Mind's Canvas

With visual exposure paving the way, the philosophical currents deepened. The teachings of Zen Buddhism gained significant traction in the West, particularly through figures like D.T. Suzuki, whose influential lectures at Columbia University introduced Zen concepts to a generation of intellectuals and artists. Alan Watts, with his accessible writings, further popularized Eastern thought, making its principles understandable to a broader audience. Beyond them, artists and composers like John Cage actively studied Zen, finding in its philosophy a profound resonance with their experimental approaches. Cage's embrace of chance operations and indeterminacy, for instance, directly mirrored Zen's emphasis on non-intention and allowing things to simply be. This created a fertile intellectual ground where Eastern philosophies could mingle with Western artistic experimentation. Artists and intellectuals were drawn to Zen's emphasis on direct experience, intuition, and the unity of mind and body – all concepts that resonated deeply with the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist ethos. It offered a philosophical framework for the visceral, non-representational art they were creating, emphasizing the process of creation over the finished product, and a non-dualistic view of the artist and their work. Concepts like mushin (no-mind), where spontaneous action flows unimpeded by conscious thought, directly paralleled the Abstract Expressionists' desire for raw, unmediated expression. This "no-mind" state, where the ego steps aside for pure action, is something I strive for in my own moments of creation – that elusive flow state where the brush simply moves without deliberation. Furthermore, the pervasive influence of existentialism in post-war America, with its focus on individual freedom, responsibility, and the search for meaning in an absurd world, created a receptive environment for Zen's emphasis on presence, immediacy, and personal enlightenment. Zen offered a path to authentic being, a way to find meaning not in external structures, but in the present, unmediated act—a powerful balm for existential angst. My own work, I like to think, often grapples with similar ideas of internal landscapes and spontaneous expression, much like the abstract concepts I explore in my how to abstract art guide. This wasn't about copying forms, but about internalizing a way of being and a mode of creation.

Echoes in Technique and Materiality: Shared Principles

The convergence wasn't just happenstance; it was built on deeply resonant shared principles that manifested in both technique and the artists' relationship with their materials. Here's a look at the profound parallels:

- Gesture and Spontaneity: Both Shodō and Action Painting (a key branch of Abstract Expressionism) prioritize the act of creation itself. Jackson Pollock's famous "drip paintings" – where he poured, flung, and dripped paint onto canvases laid on the floor – shared a spirit with the calligrapher's unhesitating, full-body stroke. It was about the process, the dance, the visceral connection between artist and material, a direct conduit from inner state to outer expression. The calligrapher's commitment to the irreversible mark, with no possibility of erasure, found its echo in Pollock's refusal to correct or refine, celebrating the authenticity of the moment and the raw energy of his bodily presence. This focus on the energetic mark is a core principle in the language of line in abstract art.

- The Power of the Line and Mark-Making: Artists like Franz Kline were deeply impressed by Japanese calligraphy. His monumental black-and-white canvases, with their bold, sweeping brushstrokes, powerfully echo the grand character forms of Shodō. They're not depictions of lines; they are lines, imbued with their own energy and presence, much like the Zen master's single, decisive stroke that carries profound meaning. The calligrapher's mastery of kasure (dry brush streaks) to create dynamic texture in a single stroke finds a direct parallel in Kline's expressive, often broad, black marks that seem to tear across the canvas. Kline himself explicitly expressed admiration for Eastern art, noting its emphasis on the expressive quality of line as a direct translation of thought and emotion. Robert Motherwell, another prominent Abstract Expressionist, also translated his engagement with Zen and existential themes into his iconic "Elegies to the Spanish Republic" series, where the weighty, abstract forms possess a distinct calligraphic force, conveying universal emotions through bold, essential marks. Motherwell often spoke of the importance of gesture and the raw act of painting, creating forms that feel both monumental and deeply personal, much like a powerful calligraphic character. For a different but equally compelling take on gestural abstraction, consider the poetic lines of Cy Twombly.

Later, artists like Christopher Wool also explored this power of the mark, as seen in his raw, expressive canvases, demonstrating the enduring impact of direct mark-making.

- Emptiness and Space (Ma): In Japanese aesthetics, the concept of Ma – the meaningful space between elements – is crucial. It's not just empty; it's active, allowing forms to breathe and resonate. Crucially, in Shodō, the white space of the paper is never passive background; it's an active participant, defining and amplifying the power of the ink stroke. This concept of Ma is closely related to Zen's idea of mu (nothingness or emptiness) not as a void, but as a potential, a space charged with meaning and possibility, a canvas awaiting creation. Abstract Expressionists, too, began to understand the importance of negative space as an active, compositional element. Think of the expansive, breathing color fields of a Mark Rothko painting, or the stark, activating "zips" in Barnett Newman's work; these aren't just empty backgrounds, but active participants in the visual dialogue, creating a sense of awe and contemplation, much like the sacred space around a Zen garden's rock arrangement. In a Franz Kline painting, for instance, the bold black strokes don't merely sit on a white canvas; the white space actively pushes against and defines the black forms, creating a dynamic tension and emphasizing the expressive power of the void. It's something I think about a lot when composing my own pieces – sometimes what's not there speaks louder than what is. It's in the quiet spaces that the true energy often resides, a testament to the power of negative space in abstract art.

- Direct Engagement with Materials and the Embrace of Imperfection: The calligrapher's intimate, almost spiritual, relationship with their materials – the animal hair brush becoming an extension of the body, the ink a living substance, the paper a responsive surface – found a powerful echo in the Abstract Expressionists' physical engagement with paint and canvas. For the calligrapher, the brush is a conduit for chi; for the action painter, paint was not merely a medium for representation but a raw, physical entity to be slung, dripped, and smeared, responding directly to the artist's bodily energy and emotional state. Both approached their materials with a profound respect for their inherent qualities and potential for expression, often valuing the auditory experience of creation – the brush on paper, the drip of paint – as much as the visual. This also extended to the philosophy of wabi-sabi, finding beauty in the natural processes, imperfections, and transience of materials, which resonated with the Abstract Expressionists' rejection of polished perfection in favor of raw authenticity. I often find myself listening to the scrape of my palette knife or the drag of the brush, finding rhythm and intention in the sounds as much as in the visual output. It's a dialogue with the medium itself.

- Inner Experience and Spirituality: Both movements, in their own ways, sought to express an inner reality, a spiritual or emotional truth, rather than just objective representation. The Zen influence in Shodō, with its emphasis on direct experience and enlightenment (satori), and the existential angst and introspection of Abstract Expressionism, shared a common ground in this pursuit of the intangible. It was a quest for authenticity, a desire to reveal the hidden depths of human experience through pure form and unmediated gesture, a kind of visual meditation. The concept of yūgen – a profound, mysterious sense of beauty and the awareness of the universe that triggers emotional responses, often tinged with sadness or reverence – can be seen to resonate with the evocative power and spiritual aims of many Abstract Expressionist works, especially the more contemplative color field paintings. For more on this broader connection, our article on the enduring influence of Japanese aesthetics on Western abstract art is a great read.

Addressing Misconceptions: Beyond Direct Imitation

It's important to clarify that the influence of Japanese calligraphy on Abstract Expressionism was rarely about direct imitation of specific characters or styles. Instead, it was a deeper cultural osmosis, an internalization of fundamental principles. Western artists weren't typically learning to write Kanji; rather, they were absorbing ideas about gesture as expression, the spiritual dimension of mark-making, the power of negative space, and a profound respect for the process of creation that resonated with their own search for a new artistic language. It was a shared philosophical current more than a stylistic appropriation. While some critics at the time noted superficial similarities, the deeper connection was often recognized retrospectively, as scholars pieced together the intellectual and cultural landscape of the post-war era. It was less about painting like a calligrapher and more about finding a shared spirit of creation, a parallel evolution born from similar needs for unmediated expression. Not every Abstract Expressionist was explicitly studying Zen or Shodō, but the ideas were 'in the air,' influencing the broader artistic consciousness, leading to a new chapter in abstract art movements.

Key Takeaways: The Threads That Bind

To quickly recap, the powerful connection between Japanese calligraphy and Abstract Expressionism can be understood through several key shared principles:

- Emphasis on the Act: Both value the process of creation and the artist's physical engagement over a predetermined outcome.

- Unmediated Gesture: The unhesitating, spontaneous mark as a direct conduit for inner emotion and thought.

- Active Space (Ma): The recognition of negative space as a vital, compositional element, not mere background.

- Material Reverence and Wabi-Sabi: A deep respect for and intimate relationship with the inherent qualities of the artistic medium, embracing imperfection.

- Spiritual Resonance: A quest for inner truth, authenticity, and profound meaning, whether through Zen enlightenment or existential self-discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was the influence of Japanese calligraphy on Abstract Expressionism direct or indirect?

Primarily indirect, though profoundly significant. It wasn't typically about specific Abstract Expressionist artists directly studying Shodō with Japanese masters, but rather a profound cultural absorption. This occurred through exhibitions of East Asian art in the West, widely circulated publications showcasing Japanese aesthetics (including the radical Gutai group), and the widespread popularity of Zen Buddhist philosophy after WWII, particularly through influential figures like D.T. Suzuki and Alan Watts. The similarities in gestural qualities, spontaneity, and philosophical underpinnings were observed and embraced, leading to more of a shared understanding and absorption, rather than direct lessons. While no formal training links exist for most, many critics and academics of the time, and certainly in retrospect, have acknowledged these parallels.

Which Abstract Expressionists were most influenced?

Artists like Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock are often cited for their stylistic and philosophical parallels to Japanese calligraphy. Kline's bold black-and-white compositions, such as his "Mahoning" (1956), bear a striking resemblance to monumental calligraphic characters, and his masterful use of kasure evokes dry brush techniques to create dynamic movement. Kline explicitly stated his admiration for the energy and directness of Eastern art. Pollock's action painting, exemplified by works like "Number 1A, 1948," shares the gestural spontaneity and all-over composition found in some calligraphic traditions, where the entire canvas becomes an arena for the artist's uninhibited movement, a direct parallel to the full-body movement of a calligrapher. His interest in Native American sand painting and other non-Western art forms further points to a broader openness to non-European aesthetic principles. Motherwell, deeply engaged with Zen philosophy and existentialism, translated his understanding into his "Elegies to the Spanish Republic" series, where weighty, abstract forms convey existential themes with a powerful calligraphic force and a deliberate balance of form and void, seen in pieces like "Elegy to the Spanish Republic, No. 34" (1953-54). He often discussed the 'subjective automatism' in painting that echoed Zen's focus on the unconscious mind.

How did Zen Buddhism specifically impact Abstract Expressionism's philosophy?

Zen Buddhism offered a framework that validated the Abstract Expressionists' pursuit of intuitive, unmediated expression. Concepts like satori (enlightenment through direct experience), mushin (no-mind, or freedom from conscious thought), and the emphasis on process over product resonated deeply. Zen provided a philosophical justification for the visceral, non-representational act of painting, encouraging artists to bypass intellectual deliberation and allow their inner state to manifest directly on the canvas, fostering a more authentic and spontaneous artistic output. It aligned with the existentialist search for meaning in authentic, subjective experience, providing a spiritual dimension to the raw, personal expression sought by the Abstract Expressionists.

Is there a modern continuation of this dialogue?

Absolutely! The dialogue continues in contemporary art. Many artists today, myself included, draw inspiration from both Eastern and Western traditions. The emphasis on gesture, mark-making, the meaning of negative space, the spiritual dimensions of abstraction, and the respect for materials remains a potent force in the art world. It’s part of the ongoing history of abstract art, a testament to the timeless nature of these artistic principles. This ongoing conversation is a key aspect of contemporary abstraction.

Conclusion: The Enduring Echoes

The story of Japanese calligraphy's influence on Abstract Expressionism is a beautiful testament to the interconnectedness of human creativity, an "unseen link" that continues to inspire. It’s a tale of ancient wisdom meeting modern angst, of disciplined spirituality finding expression in raw, explosive gestures, and the profound power of a single, decisive mark. It reminds us that art is never created in a vacuum, but is always part of a larger, evolving conversation across cultures and centuries. For me, it's a quiet inspiration, a reminder to embrace the moment, the gesture, and the inherent spirit in every single brushstroke, however wild or serene. I often think about the calligrapher's commitment to the irreversible mark; it encourages me to let go of the need for perfection and instead embrace the authenticity of the first, most intuitive gesture. When I sit down to create, whether it's a vibrant print or a large-scale painting you might find for sale, I often find myself thinking about that calligrapher's moment of truth, the way a single line can carry so much weight, or how the white space around a form can define its power. This philosophy has certainly shaped my artistic timeline and continues to inform the pieces I exhibit, sometimes even at the museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. It's all part of the grand tapestry of abstract art, a journey of discovery that's as much about my inner landscape as it is about the canvas before me. What "unseen links" do you discover in your own creative explorations?