The Zero Group: A Definitive Guide to Post-War Abstraction's Purity, Legacy, and My Artistic Reset

Have you ever felt the urgent, almost primal urge to hit reset? To wipe the slate completely clean, to find that silent, potent moment before a new beginning, especially after something undeniably vast and… well, truly messy? I remember one time, after a particularly frustrating series of studio experiments, feeling that absolute necessity to strip everything back, to reclaim the raw canvas, the bare essentials. That's precisely how I imagine the art world felt after World War II. The crushing weight of history, the deep shadow of destruction – it demanded not just new art, but a fundamentally new artistic language. The existing artistic expressions, like the emotional intensity of Abstract Expressionism, suddenly felt inadequate, too burdened by individual turmoil in a world craving universal hope. What was needed was something pure, something fresh, something utterly unburdened by the past's emotional narratives. A zero hour. It was a philosophical stance, a deliberate rejection of the prevailing existential angst, seeking instead a universal language of hope and renewal. This article will explore the brilliant, radical, and surprisingly zen spirit of the Zero Group, revealing how their vision still speaks to me on a deeply personal level today, influencing my own search for simplicity and impact.

Wiping the Slate Clean: What Was the Zero Group, Anyway?

Imagine Düsseldorf, Germany, in the late 1950s. The established art scene was still grappling with the echoes of Abstract Expressionism and Tachism – expressive, often turbulent, and deeply personal forms of abstraction that poured the artist's inner turmoil onto the canvas. But a small, visionary group of artists, primarily Otto Piene and Heinz Mack, with Günther Uecker joining soon after, felt a profoundly different calling. They weren't interested in inner turmoil or the heroic brushstroke; they wanted to look outward, to the fundamental, objective elements of existence: light, space, movement, and time.

Their aim was nothing short of a 'zero hour' – a philosophical concept symbolizing a point of absolute silence, purity, and universal potential before a new beginning. It was a deliberate, almost spiritual, rejection of the existential angst that permeated much of contemporary art. They sought a tabula rasa, a clean slate, not just as a metaphor for starting over, but as a practical artistic principle: stripping away subjective expression and historical burdens to build anew from universal, objective principles. It makes me think of those moments in my own studio when a painting isn't quite working, and I just want to scrape it all off, or simply start with a fresh, pristine canvas. That's the 'zero' mindset for me – a liberating, almost meditative act of cleansing, a surrender to pure potential. It's a kind of artistic minimalism, a forced return to the essential, allowing the material and elemental forces to speak for themselves.

This wasn't a rigid style with a manifesto etched in stone, but rather a collective spirit, a shared vision across borders. They rejected the canvas as a window to the soul, and instead sought to create art that was experiential, dynamic, and often ethereal. This radical shift, driven by a desire for a clean slate, echoed similar sentiments in international movements. You could see parallel quests for purity and elemental forms in Piero Manzoni's 'Achromes' with Italy's Azimuth Group, which stripped painting down to its material essence, removing all color and expressive content. Artists like Enrico Castellani and Agostino Bonalumi, while part of a broader Italian scene, also explored the rhythmic potential of the monochrome surface, creating art that focused on material interaction with light and shadow. The precise, reductive works of the Dutch Nul group, led by Armando, shared Zero's emphasis on seriality, industrial materials, and a cool, objective aesthetic, though often with a stricter adherence to formal principles. Even Yves Klein, with his iconic monochromes and explorations of immateriality, shared a conceptual space, pushing the boundaries of what art could be, though his spiritual approach differed significantly from Zero's more objective stance. In Japan, the Gutai group, while more focused on performance, raw material, and the artist's body, shared Zero's desire for a radical new beginning, albeit through a more visceral and often chaotic energy. This signaled a global hunger for new artistic languages that transcended personal drama, embracing objectivity and universal experience. If you're interested in understanding the broader context of this radical shift, take a look at my guide to post-war abstract art movements.

The Language of Light and Shadow: Elemental Forces in Zero Art

The Zero Group spoke a language of elemental forces, a far cry from the emotional narratives of their predecessors. They pushed boundaries, experimenting with materials and processes that were utterly revolutionary for their time. It's truly fascinating how they managed to find such profound expression in what seemed like such simple, stripped-back approaches, often embracing industrial materials and new technologies over traditional art supplies. They weren't afraid to use anything from nails and feathers to motors and light bulbs to explore their core themes of light, movement, space, and structure.

Light as Medium – Otto Piene

For artists like Otto Piene, a key theoretician of the group, light wasn't just something that illuminated a painting; it was the medium itself. He created mesmerizing 'light ballets' and 'light rooms,' where projectors, lamps, and moving elements cast ever-changing patterns of light and shadow, transforming space and perception. Imagine art that breathes, shifts, and dances – it's less about a static object and more about an ephemeral, immersive experience, often theatrical in its presentation, challenging the viewer's fixed perspective. Piene also famously experimented with fire and smoke in his 'Rauchbilder' (smoke paintings). He would apply solvent to a canvas, ignite it, then control the resulting smoke and soot to create evocative, often ethereal, images. It was a fearless, almost alchemical approach, harnessing destructive forces for creative ends, seeking purity through transformation and the raw energy of natural elements. This controlled destruction and the emergence of form from chaos felt deeply symbolic for a post-war generation. It makes me think of the exhilarating fear I sometimes feel when working with new, unpredictable mixed media in my own studio – that push-and-pull between control and letting the material dictate its own form. The interplay of translucent forms and light in abstract work like this can evoke that dynamic energy Zero artists sought:

Movement and Structure – Heinz Mack

Moving from Piene's ethereal explorations, Heinz Mack, on the other hand, was deeply engaged with movement and optical vibration, a concept he termed 'light-dynamics'. His kinetic reliefs, often made of aluminum or other reflective industrial materials, caught and reflected light, creating shimmering, pulsating surfaces that changed with the viewer's perspective. It was art that demanded active engagement, inviting you to move around it, to watch it come alive through its interaction with the environment and the observer. Mack's ambitious 'Sahara Project' envisioned massive light-sculptures installed in the vast, empty desert, using the epic landscape itself as a canvas for light and reflection. This was an ultimate embrace of space and environmental interaction, seeking to merge art with the raw power of nature and transcend the confines of the gallery, creating art for a universal, boundless stage. This dynamic quality, the interaction between elements to create perceived motion and an active viewing experience, is something that fascinates me in all forms of abstract art:

The Power of Monochrome and Repetition – Günther Uecker

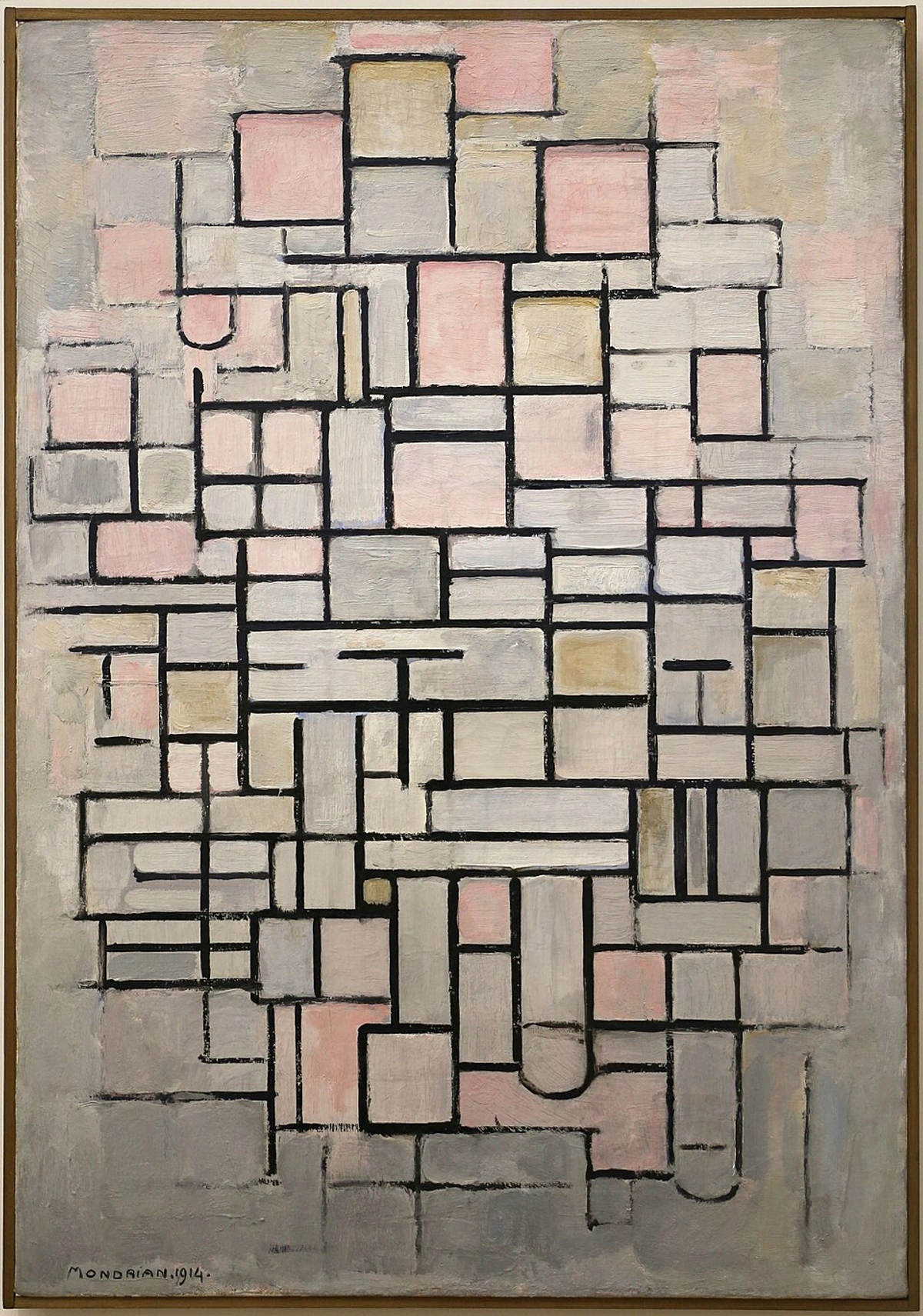

Then there's Günther Uecker, perhaps best known for his 'nail reliefs.' Yes, actual nails! Driven into canvases or panels in rhythmic patterns, these works created mesmerizing, textured surfaces that played with light and shadow in a purely tactile and optical way. The repetitive, almost ritualistic act of hammering thousands of nails into a surface became a core part of the artwork's meaning, puncturing the traditional canvas to reveal a deeper, vibrating energy. The repetition of the nails created a hypnotic, optical effect, a quiet meditation on structure and rhythm, often evoking a sense of structured chaos or a pulsating field. The nails themselves could be seen as symbolic – a ritualistic piercing of the canvas, a way to break through the surface to reveal something more fundamental, or even a structured representation of chaos. It's a testament to the power of reduction – how much meaning can you wring out of a single color, a single gesture, repeated endlessly? More than you might think, turns out. It's a stark contrast to the colorful chaos I sometimes embrace, but the underlying discipline and focus on fundamental elements are undeniable, much like the structural purity seen in earlier abstract movements. While Uecker used the aggressive, tactile act of nailing to achieve his structured forms, artists like Mondrian, decades earlier, sought similar purity through precise geometric arrangements, proving that the quest for fundamental order transcends vastly different artistic approaches, each a unique 'zero point' in its own right:

Exploring these ideas makes me appreciate the full spectrum of abstract art movements even more deeply.

Beyond Zero: A New Era of Artistic Potential

So, what exactly did Zero leave behind for us? The Zero Group might have been relatively short-lived as a formal movement, but its impact rippled across the art world, proving that a 'zero hour' could indeed spark a new artistic era. Their radical focus on the essential, the elemental, and the experiential laid crucial groundwork for subsequent movements like Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and even aspects of Land Art. Zero's engagement with universal, objective principles contrasted sharply with the subjective, emotional focus of Abstract Expressionism, marking a profound shift in artistic priorities that still resonates today. Critics at the time, however, sometimes found their emphasis on objectivity and industrial materials to be too cold, impersonal, or overly technological, lacking the emotional depth of earlier art.

Their emphasis on seriality, objectivity, and the dematerialization of the art object directly influenced artists. While Zero artists often had a strong material presence in their work, they began to shift the focus from the object itself to the viewer's experience or the underlying concept. This philosophical shift became a cornerstone, moving art beyond traditional forms to intellectual propositions and immersive experiences.

Let's look at some of these profound connections:

Zero Concept | Influenced Movement/Artist | Impact/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Seriality & Repetition | Minimalism (Donald Judd, Carl Andre) | Uecker's systematic repetition of nails directly anticipated minimalist artists' exploration of modular forms and industrial materials in series, emphasizing objectivity over personal gesture. |

| Dematerialization of the Art Object | Conceptual Art (Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth) | Shifting focus from the physical artwork to the idea, concept, or experience it created, paving the way for art as intellectual proposition, where the concept is the art. |

| Light, Space, & Environment | Land Art (James Turrell, Robert Irwin) | Piene's ephemeral light environments and Mack's 'Sahara Project' emphasized immersive experiences and art interacting directly with its environment, inspiring site-specific installations and light-based works that manipulate perception. |

| Viewer Participation | Installation Art, Kinetic Art | The demand for active engagement with Mack's kinetic sculptures and Piene's light rooms laid the groundwork for art that directly involves and changes with the viewer. |

For example, Uecker's systematic repetition and use of everyday materials, like nails, anticipated Donald Judd's exploration of industrial materials and sequential, modular forms. Piene's ephemeral light environments and emphasis on viewer experience paved the way for immersive installations and elements of Land Art, with artists like James Turrell creating entire environments out of light. The dematerialization of the art object – shifting focus from the physical artwork itself to the idea, concept, or experience it created – became a cornerstone of Conceptual Art, moving art beyond tangible forms to intellectual propositions. They taught us that art could be less about the artist's personal drama and more about universal experiences – a new way of seeing, feeling, and engaging with the world.

Key Exhibitions & Global Resonance

Zero's influence wasn't just theoretical; it was exhibited. Early seminal exhibitions in their own Düsseldorf studios and later in prominent galleries like the Schmela Gallery were pivotal for establishing their presence. Their strong presence at major international events, such as Documenta III in 1964, was particularly significant, firmly establishing their relevance on the global stage by showcasing their work alongside a diverse range of international avant-garde art. This period saw Zero artists actively fostering a vibrant, informal network of artists from across Europe and beyond – including the Gutai group in Japan, Nouveau Réalisme in France, and the Nul group in the Netherlands. This global resonance underlines the universal appeal of their quest for purity and renewal, demonstrating a shared international desire for a fresh start in art after the war. For me, seeing how these groups interacted and influenced each other really highlights the interconnectedness of human creative impulses, even across vastly different cultural contexts.

My Personal Zero Hour: Finding Purity in the Studio

Every time I approach a fresh canvas, it's a tiny 'zero hour' for me. It's that exhilarating moment of pure potential, a chance to experiment, to push boundaries, to simplify and amplify. I sometimes pause, take a deep breath, and really feel that emptiness, that quiet before the first mark. It's a meditative space where I try to strip away all preconceptions, much like the Zero artists did. The Zero Group's relentless pursuit of purity, even when embracing unconventional materials like nails or fire, constantly reminds me to strip away the unnecessary. Whether I'm exploring the nuances of line or the raw textures in my mixed media pieces, that foundational discipline is there. Their fascination with light and space also deeply informs how I think about composition, trying to create depth and dynamism from the most fundamental elements. In my own work, I often find myself wrestling with the "structured chaos" idea that Uecker explored – how to bring order to spontaneous expression, to find the underlying rhythm in a vibrant, sometimes turbulent, abstract field. It's a continuous, often messy, journey, but the zero mindset offers a beautiful clarity.

Sometimes, the most profound statements are made not with grand gestures, but with the quiet power of fundamental elements. That's the enduring lesson of Zero that resonates deeply with my own creative journey. It's a constant exploration, and if you're ever in the Netherlands, you can see some of my ongoing explorations at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch. You can also trace the evolution of my own creative journey on my timeline.

If you're keen to dive deeper into how different periods have shaped our understanding of abstraction, my guide to abstract art is a good next step. And for those wrestling with understanding abstract art or even wondering how to abstract art themselves, the Zero Group offers a compelling philosophical starting point: begin with the basics, find your own 'zero point,' and see what new possibilities emerge.

Further Reflections on the Zero Group's Vision

Why was the Zero Group so important after WWII?

After the devastation of World War II, many artists felt a profound need to break away from traditional art forms and emotional narratives. The Zero Group offered a 'zero hour' – a philosophical concept for a fresh start, seeking universal, objective principles like light, space, and movement rather than individualistic expression or existential angst. This quest for purity and renewal resonated deeply with a world yearning for new beginnings and a universal language of hope.

What challenges did the Zero Group face?

Zero Group art sometimes faced criticism for being too cold, impersonal, or overly technological, lacking the emotional depth of earlier abstract movements like Abstract Expressionism. Its emphasis on objectivity and a stripped-down aesthetic was occasionally misconstrued as mechanistic or sterile. The ephemeral nature of many of their light and movement installations also posed significant challenges for preservation and traditional exhibition formats, leading to some works being lost or difficult to reconstruct. Despite these hurdles, their forward-thinking approach profoundly influenced future art forms.

Where can I see Zero Group art today?

Major art museums worldwide, particularly those with strong collections of post-war European art, often feature works by Piene, Mack, and Uecker. The Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, where the group originated, is a key institution. Keep an eye out for retrospective shows and temporary exhibitions dedicated to Zero artists, as their work continues to be highly sought after and exhibited.

How is Zero Group art still relevant to contemporary art?

Absolutely! Their emphasis on environmental art, interactive installations, and the philosophical shift towards the dematerialization of the art object resonates strongly with contemporary practices. Their exploration of light, space, and experience continues to inspire artists, collectors, and thinkers interested in pushing beyond traditional art forms. We see their legacy in everything from large-scale light art installations and immersive digital experiences to process-based abstract art and minimalist sculpture. Their influence can be seen in contemporary art available to buy today, reflecting their enduring impact on artistic practice and a continued fascination with pure forms and engaging experiences.

Final Thoughts: The Enduring Spark of Zero

The Zero Group were trailblazers, artists who dared to dream of a new beginning, not just for art, but for a world recovering from immense trauma. Their pursuit of purity, their fascination with light and movement, and their embrace of the ephemeral left an indelible mark. They remind us that sometimes, the most profound statements are made not with grand gestures, but with the quiet power of fundamental elements. So next time you're looking at a seemingly simple abstract piece, take a moment. Consider the 'zero hour' from which it might have emerged, and how that purity of intent can still spark something truly extraordinary within you.