The Enduring Echo: Unpacking Skull Symbolism in Art, Culture & Life

Explore the rich and evolving symbolism of skulls in art, from ancient rituals and memento mori to contemporary expressions of identity and life's profound truths, through a curator's personal lens. Discover its global impact.

The Enduring Echo: Unpacking the Symbolism of Skulls in Art History and Life

There are some images that lodge themselves in our collective consciousness, speaking a language older than words. For me, as a curator, the skull is undoubtedly one of them. I find myself continually drawn to its stark, often unsettling, yet profoundly resonant form. It’s a motif that, at first glance, might seem solely macabre – the kind of thing you'd expect to see lurking in a dimly lit Gothic novel, right? But its journey through art history reveals a spectrum of meanings far richer and more nuanced than mere morbidity, hinting instead at its profound connection to life itself. So, if you're ready to dive a bit deeper into this 'heavy' topic (don't worry, it’s far more about life’s enduring truths than just the end!), join me as we peel back the layers of skull symbolism in art.

A Timeless Motif: Why Skulls Persist

Think about it: from the earliest human settlements to today's vibrant street art, the skull appears again and again. Why this enduring fascination with what is essentially a stark reminder of our own mortality? My take is that the skull forces us to confront fundamental questions about life, death, identity, and legacy. It’s a silent, undeniable truth-teller, stripped bare of flesh and ego, leaving only the essential structure of what once was. It's this raw confrontation with our finite nature, I think, that sparks the philosophical reflection many cultures have sought in art – a stripped-down truth not unlike the foundational truths I try to capture in my own abstract works, focusing on elemental forms and vibrant energies.

Historically, the depiction of the human skull in art has often served as a powerful memento mori – a Latin phrase meaning 'remember you must die'. This isn't necessarily about fear, which I think is a common misconception; rather, it's a philosophical reflection, urging us to consider the brevity of life and, by extension, to live more meaningfully. It's a concept I find particularly compelling, as it encourages a deeper engagement with our existence. It’s a challenge to embrace the now, a sentiment I often explore in my art by emphasizing vibrant, fleeting moments of color and form, almost a joyous defiance of the fleeting.

Ancient Echoes: Skulls Across Civilizations

While the Renaissance and Baroque periods are perhaps most famously associated with skull symbolism, its roots stretch much further back. In many ancient civilizations, the skull wasn't just about death; it was often a symbol of power, a protective ward, or even a revered ancestor. It's a journey that takes us from sacred rites to early philosophical musings, showing a universal human grappling with the unknown.

Mesoamerican Reverence

Take pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, for example. Skulls were integral to rituals and monumental art. The Aztec Tzompantli, or skull racks, were grim but powerful displays, often adorned with the skulls of sacrificial victims. Far from simple barbarity, these structures, dedicated to deities like Huitzilopochtli (god of war and sun) and Tezcatlipoca (god of the night sky, ancestral memory), symbolized the vital cycle of sacrifice and rebirth, the triumph of the gods, and the very sustenance of the cosmos – a profound, albeit brutal, affirmation of life's continuity. It was their way of feeding the sun, ensuring the world kept turning. We also see similar motifs, though perhaps less overtly, in Maya art, emphasizing a shared reverence for the powerful energy linked to the head.

Celtic Power and Wisdom

Or consider early Celtic traditions, where the head, revered as the seat of the soul and divine power, led to ritualistic head-hunting and the depiction of skulls in revered stone carvings as potent sources of protection and wisdom. To the Celts, the head was not just a body part, but the essence of a person, a conduit to ancestral power and the spiritual realm. Imagine the sheer weight of belief carried by such an image.

Egyptian Identity and Passage

Even in Ancient Egypt, where the focus was often on preserving the body for the afterlife, skulls found their place. While not always depicted overtly, the very process of mummification and the careful placement of the head in funerary rituals speak to a profound reverence for the skull as the seat of identity and a vessel for the eternal soul (Ka and Ba). For them, it was less about immediate mortality and more about the transition to the next realm, ensuring recognition and continuation of the self.

Greco-Roman Philosophy

In Ancient Greece and Rome, skulls appeared in funerary art, often as small, subtle reminders on sarcophagi or in philosophical contexts, echoing the Stoic and Epicurean contemplation of life's brevity. Think of the Roman phrase omnia mors aequat ('death makes all things equal'), a sentiment powerfully embodied by the skull, reminding us that even the most powerful emperor eventually faces the same fate as a common laborer.

Early Christian Redemption

In some early Christian contexts, skulls appear at the foot of the cross, symbolizing Golgotha, 'the place of the skull.' This isn't just a geographical marker; it links Christ's sacrifice to universal mortality and redemption, the new life offered in the face of death, echoing the idea of Christ's triumph over sin and death, literally at the place of the skull of Adam. Beyond this, early Christian iconography, such as depictions of saints like St. Jerome, often includes a skull, not just as a nod to mortality, but as an emblem of ascetic contemplation. It's about renouncing worldly vanities to focus on higher truths and the eternal soul, a dedication I often find myself contemplating when stripping my own art back to its most essential forms, seeking an almost spiritual purity in my abstract explorations.

Global Echoes: Skull Symbolism Beyond the West

To truly appreciate the skull's enduring resonance, we must look beyond Western art history. Its power is recognized globally, often with unique and profound interpretations, showing a diverse yet interconnected human response to mortality.

Tibetan Buddhism: Impermanence and Enlightenment

Tibetan Buddhism offers a particularly deep perspective. Skulls feature prominently in tantric Buddhist art, particularly in mandalas and ritual objects like the kapala (a skull cup often made from a human cranium). Here, they don't symbolize morbid fear but represent the impermanence of life, the illusion of the ego, and the attainment of enlightenment through the transcendence of earthly attachments. The kapala, for instance, is not just a symbol but a ritual implement used in tantric ceremonies. Initiates might drink from it during specific rites, a direct confrontation with the fear of death and attachment to the physical self, thereby serving as a powerful reminder of spiritual liberation – a means to stare directly at the impermanent and find peace.

Japanese Art: Fleeting Beauty and Spirit Worlds

In Japanese Art, from samurai imagery where a skull could symbolize the acceptance of death in battle and the honor of one's lineage, to Ukiyo-e woodblock prints (like those depicting gashadokuro – giant skeleton monsters formed from the bones of those who died of starvation) or ghosts, skulls often represent the fleeting nature of beauty and life (mono no aware – the bittersweet awareness of impermanence and the pathos of fleeting things, like the falling cherry blossoms). They also connect to the spiritual realm, reminding us of the thin veil between worlds. If you're fascinated by this artistic tradition, you might enjoy exploring the enduring legacy of Ukiyo-e: Japanese woodblock prints and their global impact.

African Art: Ancestral Power and Cycles

In various African tribal masks and sculptures, skulls or skeletal motifs are often used to represent ancestors, spiritual guides, or deities. Consider, for instance, the Fang reliquary figures of Gabon, where the skulls of revered ancestors were often housed in bark boxes, with carved wooden figures (sometimes featuring skull-like faces) guarding them. In other traditions, like the Dogon of Mali or the Igbo of Nigeria, masks with skull-like features are used in ceremonies to honor ancestors, facilitate transitions, or connect with spiritual forces. These figures and motifs embody wisdom, the cycle of life and death, and can serve as powerful conduits between the living and the spirit world, especially in rites of passage or funerary ceremonies, ensuring a continuation of spiritual power and community memory. These aren't objects of fear, but of profound reverence and connection.

Indigenous Art: Connection to the Land and Spirit

Beyond these, various indigenous cultures around the globe have integrated skull symbolism into their art and practices. From some Native American traditions where skulls might signify war, vision quests, or respect for the deceased, to Oceanic cultures using human bones in ancestral veneration or ritualistic displays, the skull consistently serves as a powerful link to heritage, land, and the spirit realm, affirming cycles of existence that transcend individual lives.

Sugar Skulls: A Vibrant Celebration

Mexico's Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) offers perhaps the most vibrant and celebratory interpretation of the skull. The iconic sugar skulls (calaveras de azúcar) are not grim reminders of death but joyous, edible folk art. Intricately decorated with colorful icing, glitter, and names, they are crafted to honor and remember deceased loved ones. These skulls symbolize a playful, accepting relationship with death, a belief that the dead remain part of the community and that life is a cycle to be celebrated. It’s a powerful reminder that mortality doesn't always have to be somber; it can be an explosion of color and memory, much like the vibrant explosions of color I often use to celebrate existence in my own art.

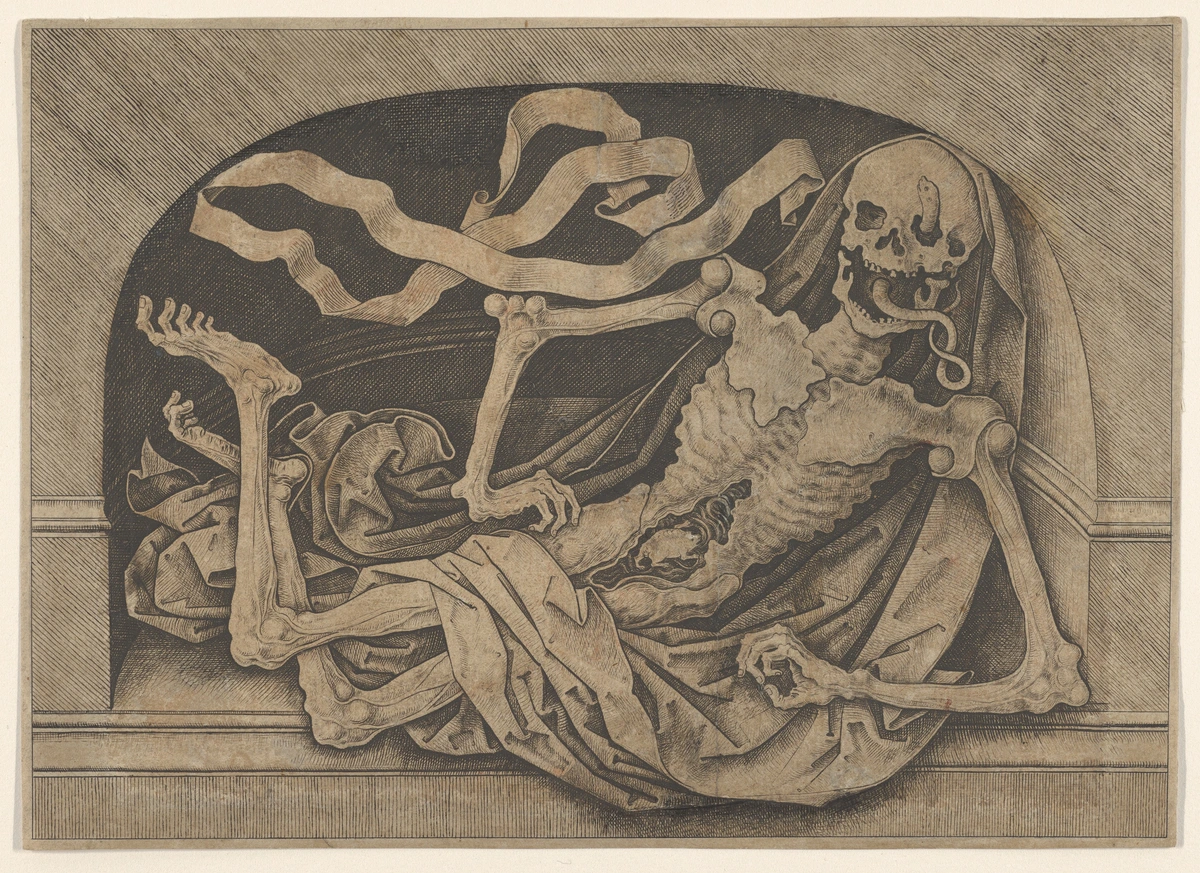

Medieval Reflections: The Emergence of Memento Mori

It's really in the late Medieval period, and then truly exploded in the Renaissance and Baroque eras, that memento mori became a dominant theme in Western art. With devastating plagues like the Black Death and constant warfare, death was an ever-present reality. This era saw artists integrating skulls into portraits, altarpieces, and intricate sculptural works, and even illuminated manuscripts, often with a stark realism that mirrored the direct, unsparing confrontation with mortality in daily life. I see them as visual sermons, speaking to a world grappling with fleeting earthly power and the fragility of life. The skull reminds everyone, king or commoner, that death is the ultimate equalizer, stripped of all earthly pretense.

Works like the anonymous medieval woodcuts of the Danse Macabre (Dance of Death) visually captured this sentiment, showing figures from all walks of life – popes, emperors, peasants – being led away by skeletal personifications of death. These were not merely religious warnings but profound societal commentaries, highlighting social inequalities while simultaneously declaring death's universal reach. They weren't designed to terrify, I believe, but to instill a sense of humility and purpose. They whisper a timeless message: make your time count, for it is finite. It's a beautiful, if somber, paradox.

Renaissance and Baroque: The Golden Age of Mortality

This era truly embraced the skull, not just as a general reminder of death, but with increasing artistic sophistication and specific philosophical intent, blending piety with a fascination for the material world.

Memento Mori Masterpieces

Artists like Hans Holbein the Younger masterfully embedded skulls within their portraits. His famous painting The Ambassadors (1533), for instance, contains an anamorphic skull – a distorted image that only becomes clear when viewed from a specific angle. It's a brilliant, subtle, yet inescapable memento mori, reminding the powerful subjects (and viewers) of their mortality amidst worldly possessions. To me, this clever visual trick underscores how deeply artists integrated these themes, challenging us to look beyond surface appearances and find deeper truths, much like I invite viewers to do with the layers in my own abstract compositions.

Vanitas: The Fleeting Spectacle of Earthly Pleasures

Closely related to memento mori, particularly in 17th-century Dutch art, is the concept of vanitas. A vanitas painting is a symbolic work illustrating life's transience and the futility of worldly pursuits. It is a specific genre of still life that heavily employs memento mori themes, often juxtaposing symbols of pleasure and wealth with those of decay. A skull in a vanitas still life isn't just about death; it's a commentary on the ultimate emptiness of material pursuits and earthly glory in the face of inevitable decay.

Think of a lavish spread of fruit, jewels, books, and musical instruments, all meticulously rendered, yet juxtaposed with a skull, a guttering candle (life extinguishing), soap bubbles (fleeting pleasure), an hourglass (passage of time), wilting flowers (ephemeral beauty), or even insects like flies or worms (decay, the inevitability of physical corruption). Artists like Pieter Claesz and Willem Kalf were masters of this visual argument. For me, these works are incredibly eloquent, prompting us to question what truly holds value. Is it the gold and silks, or the intangible experiences and wisdom we gather? It’s a bit like arranging the most beautiful, expensive dinner party, only to realize the bill for eternity is about to arrive. For a deeper dive into how broader symbolic language is used, you might find my thoughts on understanding symbolism in contemporary art insightful.

Enlightenment's Gaze: From Morality to Anatomy

As Europe moved through the Enlightenment, the overt religious and moralizing use of the skull waned slightly, giving way to scientific inquiry and a more rational understanding of the human body. The shift was quite profound: from a spiritual reminder to a scientific object of study.

Think of early anatomical studies and groundbreaking works like Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica. Vesalius meticulously depicted the human skull and skeleton, not as a symbol of impending doom, but as a marvel of biological engineering. His empirical approach, shared by other early medical illustrators who created detailed anatomical plates, directly challenged centuries of anatomical dogma, establishing a new scientific methodology. In this context, the skull wasn't primarily a memento mori but an elegant container of the brain, the foundation of human identity, and a profound study in form and structure. This period also saw nascent fields like phrenology, which, though now a discredited pseudoscience, sought to 'read' character in skull shape, claiming to correlate bumps and indentations with specific mental faculties – a fascinating, if misguided, attempt to rationalize and categorize the very structure of our being. It reminds me that even when stripped of all its cultural baggage, the skull holds an undeniable, almost stark, beauty in its pure anatomical truth, much like the fundamental shapes I explore in my own art. It's a raw structure that forms the very core of our being, a testament to fundamental design. If you find the exploration of form fascinating, you might enjoy my thoughts on understanding form and space in abstract art.

Beyond art, the skull became a crucial tool in forensics and archaeology, allowing scientists to reconstruct past lives, determine identities, and even deduce causes of death from ancient remains. For instance, the detailed study of ancient skulls has revealed migration patterns of early humans and insights into their health and diet, making it a silent witness and a key to unlocking secrets of humanity's past, albeit through a purely scientific lens.

Romanticism's Embrace: Melancholy, Mystery, and the Sublime

The skull soon re-emerged with renewed force in the 19th century, transformed by new philosophical currents. The Romantic movement, with its emphasis on emotion, the sublime, and the darker, often terrifying, aspects of human experience, found fertile ground in the skull's potent imagery, contrasting sharply with the Enlightenment's cool rationalism. For Romantics, the sublime wasn't just beauty, but beauty mixed with terror, grandeur, and an overwhelming sense of awe – exactly what a skull could evoke.

Artists and writers alike, such as Théodore Géricault (Heads of the Executed, unflinching studies of severed heads from the morgue) and Edgar Allan Poe in his macabre tales, embraced the skull not merely as a reminder of death, but as a symbol of melancholy, mystery, and the terrifying beauty of existence. It was about confronting the unknown, the limits of reason, and the raw, often unsettling, truth of human suffering. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, for example, while not explicitly depicting skulls, explores the transgression of life and death boundaries through Victor Frankenstein's ambition to reanimate the dead, a theme deeply resonant with the skeletal imagery of mortality. It dared us to look into the abyss and find a strange kind of beauty there, a sentiment that resonates deeply with the introspective moments in my art.

The Modern & Contemporary Skull: Rebellion, Identity, and Celebration

As the world hurtled into the 20th century, the skull, no longer bound by its historical interpretations, underwent a radical reinvention, shedding its traditional skins to embrace new layers of meaning and serve as a potent symbol of rebellion, identity, and even celebration. I find this adaptability fascinating, showing the symbol's inherent power to resonate across diverse ideologies and challenging established norms.

20th Century Avant-Garde and Beyond

In the early 20th century, avant-garde movements occasionally used the skull in acts of artistic rebellion or social commentary, pushing boundaries and challenging viewers to look beyond surface appearances. Surrealism, for instance, with artists like Salvador Dalí, might embed skulls in dreamlike, unsettling compositions to probe the subconscious, explore primal fears, or create an uncanny sense of disquiet. Consider Dalí's Face of War (1940), where a distorted, skull-like face is riddled with more skulls, representing the cyclical horror of conflict – the skull here representing a raw, unfiltered psychological truth. By the later half of the century, the skull began to broadly shed its religious or moralizing overtones, embracing a spectrum of new interpretations – from the defiant imagery of counter-culture movements to the introspective musings of conceptual artists.

The Contemporary Canvas: From Basquiat to Pop Culture

Today, the skull remains a potent force in contemporary art. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat reimagined the skull (or perhaps, the powerful 'head'), infusing it with raw energy, cultural critique, and a vibrant, almost childlike intensity. His skulls, often depicted with a graffiti-like immediacy, bold colors, and his signature crown motif, feel less about death itself and more about identity, vulnerability, social commentary, or even a defiant life force emerging from urban chaos. They are bold, colorful, and impossible to ignore – a raw expression that reminds me of the primal energy I often chase in my own abstract works. His work elevated the raw human 'head' into an iconic symbol of resilience and voice. If you're interested in understanding the artist more deeply, you might enjoy my ultimate guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat.

More recently, Damien Hirst's diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007), shocked the art world. By covering a human skull with 8,601 flawless diamonds, Hirst used the ultimate symbol of mortality to provocatively comment on value, materialism, and the very nature of human existence in an age of excess. It's a statement piece that makes you stop and think, much like the old masters intended, but with a very modern twist, questioning our obsessions with wealth and permanence and essentially fetishizing death itself. For more on his provocative art, check out my ultimate guide to Damien Hirst.

Beyond the gallery, skulls permeate pop culture, from fashion to music, biker subcultures to political protest. Consider the iconic sugar skulls of Mexico's Día de los Muertos, which celebrate life, ancestry, and memory rather than mourn death. This evolution highlights the skull's incredible versatility as a communicative tool, able to adapt to new cultural contexts and convey deeply personal or collective messages.

Punk and Heavy Metal Subcultures

The skull became a quintessential emblem for counter-cultural movements, particularly within punk rock and heavy metal. Here, it shed its somber, reflective connotations to become a potent symbol of rebellion, anarchy, defiance, and a raw, unapologetic confrontation with society's norms. Think of iconic band logos like The Misfits' Crimson Ghost skull, or Motörhead's 'Snaggletooth' War Pig, and countless album covers and fashion choices where skulls screamed an anti-establishment message, embracing mortality not with fear, but with a rebellious sneer. It's a defiant roar that resonates with any artist who has challenged convention, much like I push boundaries with color and form in my own work.

More Than Mortality: Diverse Interpretations of the Skull

As we've explored, while death remains a primary association, the skull's symbolic repertoire is surprisingly broad and deeply interwoven with human experience. And it's worth noting a subtle difference: while skulls often represent the static, reflective aspect of mortality (what's left behind, the bare structure), skeletons frequently imply animation, the active dance of death, or even rebirth and magical reanimation (think of the Danse Macabre or various fantastical depictions of animated skeletons). Both are powerful, but the skull alone, in its bare geometry and inherent resilience, holds a unique gravity. Here are just a few more ways it's interpreted:

- Wisdom and Knowledge: As the elegant container of the brain, the skull can represent intellect, profound understanding, and contemplation, often seen in depictions of scholars or hermits like St. Jerome. It's a silent reminder of the seat of thought and memory.

- Equality: Stripped of all external markers like status or wealth, the skull emphasizes that beneath the skin, we are all the same – the ultimate equalizer, a silent reminder that earthly hierarchies are temporary and ultimately meaningless in the face of our shared mortality.

- Rebellion and Danger: From pirate flags (the Jolly Roger, a universal sign of danger) to punk rock album covers, biker gangs to political protest art, the skull often signifies defiance, danger, an anti-establishment stance, or even a celebration of mortality without fear. The skull and crossbones also serve as a classic warning for poison.

- Identity: Whether representing an individual's unique essence, a tribal affiliation, or a subcultural belonging, the skull can become a powerful emblem of who we are, or aspire to be, stripped to our core. Think of indigenous skull modifications or modern tattoos as deeply personal statements.

- Protection: In some cultures, skulls or skull motifs are used as powerful talismans or symbols to ward off evil spirits, bring good fortune, or protect against harm, drawing on their potent connection to life and death cycles, or the protective power of ancestors.

- Celebration of Life: As vividly seen in Mexico's Día de los Muertos, skulls can be vibrant symbols of ancestry, memory, and joyful remembrance, celebrating the lives of those who have passed, and asserting life's continuity.

- Transformation: In many traditions, the skull represents not an end, but a transition, a portal to another state of being or a symbol of rebirth. In alchemy, for example, the skull (caput mortuum, or 'dead head') is often a symbol for the initial stage of putrefaction or decomposition, a necessary 'death' of base matter before its eventual transformation into something higher.

- Resilience and Endurance: Paradoxically, as the most durable part of the human body, specifically designed to protect the most vital organ, the skull can also symbolize resilience and endurance, the ability to persist through time, a testament to what once was and what endures against the ravages of decay.

- The Unconscious/Hidden Depths: As the protective casing of the brain, the skull can also represent the unconscious mind, the primal instincts, or the hidden depths of human psychology, especially in Surrealist art or psychological thrillers, hinting at forces beyond our conscious control.

Religious Iconography Across Faiths

Beyond the early Christian and Tibetan Buddhist examples, the skull appears in other religious contexts, often signifying profound spiritual truths. In Hinduism, for instance, deities like Shiva and Kali are often depicted adorned with garlands of skulls or carrying skull bowls. These aren't morbid symbols but represent their power over death and time, the cycle of creation and destruction, and the ultimate transcendence of worldly illusions. The skulls symbolize liberation from ego and the ephemeral nature of existence, serving as reminders of the absolute reality beyond form.

Skulls in Folklore and Mythology

Beyond specific cultural art forms, skulls hold a significant place in global folklore and mythology. They often appear as symbols of otherworldly power, guardians of forbidden knowledge, or remnants of a forgotten era. In many tales, a talking skull might offer cryptic wisdom, much like Mímir's head in Norse mythology. After his decapitation, Odin preserved Mímir's head, which continued to dispense profound advice and hidden knowledge, serving as a conduit to ancient wisdom. Similarly, in the Russian fairy tale of Vasilisa the Beautiful, a glowing skull given by Baba Yaga guides and protects the heroine through impossible tasks, revealing hidden truths and offering supernatural aid. Skulls might mark the entrance to the underworld, serving as a threshold between realms. From spirits bound to their bone structures to magical artifacts, the skull consistently represents a concentrated form of power, often linked to the mysteries of life and death, an echo of ancient beliefs in the head as the seat of the soul. In some Native American legends, ancestral skulls are believed to hold the spirits of tribal elders, offering guidance and protecting their descendants.

Gothic and Horror: The Primal Fear

From the dimly lit corridors of classic literature to the silver screen, the skull became a cornerstone of the Gothic and horror genres. In works like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or Bram Stoker's Dracula, skulls and skeletal motifs underscore themes of mortality, the uncanny, and the transgression of natural order – think of reanimated corpses, forbidden experiments, or the blurring lines between life and death. The very structure of the skull, a silent testament to past life, naturally evokes a primal fear of what lies beyond. In film, the skull is a ubiquitous symbol of danger, the supernatural, or pure, visceral terror. It taps into our most primal fears, serving as a stark visual shorthand for death's inevitable grasp, a tradition that continues to evolve, making the skull a timeless icon of dread and fascination.

My Perspective: The Skull's Enduring Resonance

As someone deeply involved in art, especially the abstract, I've always been captivated by how certain symbols retain their power across millennia, continually inviting fresh interpretations. The skull, in particular, offers a unique bridge between our physical reality and the metaphysical questions that occupy our minds. It challenges us, provokes us, and ultimately, helps us to reflect. For me, the skull's enduring presence in art underscores art's fundamental role: to grapple with the big, uncomfortable truths of human existence and to find meaning in the face of the unknown.

When I work with abstract forms and vibrant colors, I'm often striving for a similar primal resonance – to evoke emotion and spark contemplation about life's fundamental forces, about the essence that remains when all else is stripped away, much like the skull does through its stark geometry. My artistic journey, like the skull's symbolism, is about stripping away the non-essential to reveal a deeper truth, an essence of what it means to be alive and conscious. You can learn more about my approach and philosophy on why I paint abstract.

So, as you explore the art that moves you, consider how symbols like the skull continue to echo through time, reminding us of our shared humanity and the profound questions that unite us – questions I strive to explore in my own vibrant canvases. If these reflections on profound themes resonate with you, I invite you to explore the pieces in my collection, which often delve into similar universal questions, albeit through the lens of abstract and vibrant color. You can always find compelling works available for purchase, or perhaps visit my art at the museum in 's-Hertogenbosch to experience them firsthand. After all, isn't that what art is all about? Connecting with something beyond ourselves, even if that 'something' is a stark, beautiful reminder of our own fleeting yet resilient existence.

Evolution of Skull Symbolism in Art: A Quick Overview

Period/Culture | Primary Interpretations | Key Examples | Key Cultural Figures/Artists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Civilizations | Power, protection, reverence for ancestors, cycles of sacrifice/rebirth, identity, spiritual vessel | Mesoamerican Tzompantli, Celtic head cults, Egyptian Ka/Ba rites, early Christian Golgotha | Aztecs, Celts, Egyptians, early Christians |

| Global Cultures (Non-Western) | Impermanence, spiritual liberation, ancestors, cycles of life/death, protection, celebration | Tibetan kapala, Japanese mono no aware (Ukiyo-e), African tribal masks, Día de los Muertos sugar skulls | Tibetan Monks, Japanese Ukiyo-e Masters, Indigenous African Artists |

| Medieval Era | Memento Mori (reminder of death), equality, social commentary | Danse Macabre woodcuts, allegorical figures of Death, Illuminated manuscripts | Anonymous Artists |

| Renaissance & Baroque | Memento Mori, Vanitas (futility of earthly pleasures), intellectual contemplation | Holbein's The Ambassadors, Dutch Still Lifes | Hans Holbein the Younger, Pieter Claesz, Willem Kalf |

| Enlightenment | Scientific inquiry, anatomical study, foundation of identity | Vesalius's anatomical atlases, medical illustrations | Andreas Vesalius |

| Romanticism | Melancholy, mystery, the sublime, human suffering, limits of reason | Géricault's Heads of the Executed, Gothic literature | Théodore Géricault, Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Shelley |

| Modern & Contemporary | Rebellion, identity, social critique, materialism, cultural celebration, transformation | Basquiat's 'Heads', Hirst's For the Love of God, Punk/Metal imagery | Jean-Michel Basquiat, Damien Hirst, Salvador Dalí |

Frequently Asked Questions about Skull Symbolism in Art

Still pondering the powerful presence of the skull? Here are some answers to questions that often pop up:

Q: What is the primary meaning of a skull in art?

A: Historically, the skull primarily symbolizes memento mori (a reminder of death) and vanitas (the transience and ultimate futility of earthly life and possessions). It serves as a profound reflection on mortality and the fleeting nature of existence, often as a call to live more meaningfully.

Q: How has the symbolism of skulls changed over time?

A: While mortality remains central, the symbolism has significantly expanded. In modern and contemporary art, skulls can represent rebellion, identity, life force, cultural celebration (e.g., Día de los Muertos), equality, wisdom, resilience, or even transformation, moving beyond purely somber connotations.

Q: Are skulls always a negative symbol in art?

A: Not at all. While often associated with death, skulls are not inherently negative. They can be seen as symbols of wisdom, protection, celebration of ancestors, spiritual liberation, or a powerful call to live life fully. Their meaning is highly dependent on cultural context and artistic intent.

Q: What is the difference between memento mori and vanitas?

A: Both relate to mortality. Memento mori is a general reminder of death, urging reflection on life's brevity and encouraging a purposeful life. Vanitas is a specific genre of still life that heavily employs memento mori themes, using various symbols (including skulls, wilting flowers, or extinguishing candles) to illustrate the transient and ultimately meaningless nature of worldly goods and pleasures in the face of death.

Q: What is the difference between skull and skeleton symbolism?

A: While related, there's a nuanced distinction. Skulls in art typically represent the static, reflective aspect of mortality – what's left behind, the bare, enduring structure. Skeletons, conversely, often imply animation, the active dance of death, the personification of death, or even rebirth and magical reanimation, suggesting movement or a dynamic interaction with life.

Q: Why do some cultures use skulls for protection?

A: In cultures where skulls represent powerful ancestors or a strong connection to the spirit world, they are sometimes used as protective talismans. The belief is that the potent connection to life and death cycles, or the enduring spirit of the departed, can ward off evil, bring good luck, or provide spiritual guidance and safety to the living.

Q: Is there a difference between skulls used in art and those in cultural rituals?

A: Yes, absolutely. While art often draws inspiration from cultural rituals, the context and intent can differ significantly. Ritualistic skulls (like a kapala in Tibetan Buddhism) are often functional objects used in specific ceremonies or practices, serving as direct conduits to spiritual realms or for meditative purposes, requiring active participation. Skulls in art, while sometimes mirroring these ritualistic meanings, are primarily aesthetic objects intended for contemplation, critique, or emotional expression within a gallery or public space. The artistic representation can explore, adapt, or even challenge the traditional ritualistic meanings, but it typically serves a different function than a ritual object.

Q: How do contemporary artists use skull symbolism today?

A: Contemporary artists often reinterpret skull symbolism, moving beyond traditional memento mori. They use skulls to comment on consumerism (Damien Hirst), explore identity and social critique (Jean-Michel Basquiat), embody rebellion in subcultures (punk/metal), or celebrate life and ancestry (Día de los Muertos). The skull's raw, iconic form makes it highly adaptable for diverse modern messages, often connecting to themes of resilience, the human condition, and the interplay between life and its inevitable end.