Simple Perspective Drawing for Beginners: Your Complete Guide to Creating Depth

Feeling intimidated by perspective drawing? I get it! Join me for an expanded, personal guide to understanding the basics of one-point, two-point, and even three-point perspective, common mistakes, using reference photos, and how to make your art feel real and grounded.

Simple Perspective Drawing for Beginners: Your Complete Guide to Creating Depth

Okay, let's talk perspective. For the longest time, just hearing the word made my brain feel like it was trying to fold itself into a tiny, impossible box. Vanishing points? Horizon lines? It all sounded so technical, so mathy, and frankly, a bit intimidating. I just wanted to draw! I wanted to capture the world, or at least make my wonky tables look less... wonky.

But here's the thing I learned, the thing that finally clicked for me: perspective isn't some scary, rigid rulebook designed to stifle your creativity. It's a tool. A really, really useful tool that helps you create depth, space, and a sense of reality in your drawings. And you don't need a degree in engineering to grasp the basics. Trust me, if I can get a handle on it, you absolutely can.

This isn't going to be a dry textbook lesson. Think of this as me, sharing what finally made sense, the simple stuff that actually makes a difference when you're just starting out. We'll keep it light, maybe even a little messy, because that's how art often is, right? We'll cover the absolute essentials, dive into the friendliest types of perspective, look at common pitfalls, talk about how you can start using these ideas to make your own art feel more grounded and real, and even touch on how it subtly informs abstract work.

A Quick Peek into History: Where Did This Come From?

Before we dive into the 'how,' let's just take a tiny detour. It's kind of fascinating to think that the principles of perspective weren't always widely understood in art. For centuries, artists drew things based on importance or what they knew, not necessarily how they looked in space. It wasn't until the Renaissance, that incredible burst of creativity and inquiry, that artists and thinkers really started to figure this stuff out. Guys like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti were pioneers, using mathematics and observation to develop the systems of linear perspective we still use today. They wanted to create a more convincing illusion of reality on a flat surface, and honestly, they nailed it. Knowing this little bit of history makes me appreciate the 'headache' a bit more – it was a genuine breakthrough!

Why Bother with Perspective Anyway? (Beyond Just 'Looking Right')

Honestly? Because it makes your stuff look right. But it's more than just technical correctness. Understanding perspective adds that crucial sense of depth that pulls the viewer in, guiding their eye towards a focal point or creating a specific mood. Think about how a low viewpoint can make something feel imposing, or how converging lines can create a sense of vastness or speed. Perspective isn't just about drawing boxes; it's about controlling the viewer's experience of space in your art.

Without perspective, drawings can feel flat, objects might appear to float or be the wrong size relative to each other, and the scene can feel confusing or even claustrophobic. It's like trying to tell a story without understanding grammar – you might get the basic idea across, but it won't flow, and key relationships will be unclear. Even if you're drawing something completely fantastical, understanding how things recede into the distance, how objects relate to each other in space, and how lines converge makes the whole image feel more believable, more grounded.

It's like learning the basic notes in music before you start improvising jazz. You can totally jump straight into abstract expressionism if that's your jam (How to Make Abstract Art: Your Ultimate & Engaging Guide), but knowing a little about how the visual world works can inform even the most non-representational pieces. It's all part of the (Elements of Art Explained: Your Ultimate Guide to Seeing Like an Artist). For me, even in my abstract work (Art for sale), understanding how shapes interact in space, how lines imply direction, it all stems from these fundamental ideas of perspective and composition.

The Picture Plane: Your Imaginary Window

Before we dive into specific types of perspective, let's quickly touch on the Picture Plane. Imagine your drawing surface (your paper or canvas) is a transparent window, and you're looking through it at the scene you want to draw. The Picture Plane is this imaginary window. Your drawing is essentially a representation of the scene as it appears flattened onto this 2D surface from your specific viewpoint. Understanding this helps frame why lines converge and objects change size – it's how they look when projected onto that flat plane. Think of it like looking through a camera viewfinder or your phone screen – you're capturing a 3D world onto a flat surface.

The Absolute, Bare-Bones Basics

Alright, deep breath. Two key things you need to know to start, and they both relate to your viewpoint and that imaginary picture plane:

- The Horizon Line (HL): This is your eye level. Imagine standing on a flat plain looking out – the horizon is where the sky meets the land. In a drawing, it's a horizontal line that represents your viewpoint. Crucially, it's always at your eye level, no matter if you're looking up, down, or straight ahead. Think about it this way: If your eyes are 5 feet off the ground, your HL is at the 5-foot mark in the scene you're drawing. If you're looking down from a tall building (a Bird's-Eye View), the horizon line is high on your page. If you're lying on the floor looking up at the ceiling (a Worm's-Eye View), your horizon line is very low on the page. If you're looking straight ahead (an Eye-Level View), it's somewhere in the middle. Want another example? Imagine looking up at a bird on a wire – your HL is below the bird. Now imagine looking down at a coin on the floor – your HL is above the coin. It's always your eye level.

- Vanishing Points (VP): These are points on the horizon line where parallel lines appear to meet and disappear into the distance. Think of train tracks or a long, straight road. They look like they converge at a single point way off in the distance. That's a vanishing point. Objects above the horizon line will have lines going down to the VP, and objects below the horizon line will have lines going up to the VP. Lines that are parallel to the horizon line (horizontal lines) and lines that are perpendicular to the horizon line (vertical lines, in one and two-point perspective) do not go to a vanishing point; they remain parallel to the edges of your page.

That's it. Horizon Line (your eye level) and Vanishing Points (where parallel lines vanish). Not so scary, right?

One-Point Perspective: The Friendly Starting Point

This is where I recommend everyone begins. It's the simplest because you're looking straight at one face of an object (like the front of a box or building), and all the lines that recede away from you go to a single vanishing point on the horizon line.

Imagine drawing a straight road disappearing into the distance, or looking directly at the front of a building. This is one-point perspective. I remember trying to draw my first simple room using this, staring at the corner of my bedroom. It felt like magic when the lines from the walls and ceiling actually met at a point on my eye level! This is also where you start seeing scale and proportion at work – objects further down that hallway or road will appear smaller, even if they are the same size in reality. Scale refers to the size of an object relative to other objects or the environment, while proportion is the size of parts of an object relative to the whole. Perspective directly impacts how we depict both; it changes the apparent scale of objects with distance while helping you maintain their correct proportion.

Here’s a super simple way to try it:

- Draw a horizon line across your page. This is your eye level.

- Put a single dot on that line. This is your vanishing point (VP).

- Draw a square or rectangle below the horizon line (this will be the front face of your object, like a box). Make sure its vertical and horizontal lines are parallel to the edges of your page.

- From each corner of the square/rectangle, draw a light line (called a perspective line or orthogonal line) extending back towards the vanishing point. These lines represent the edges of the object receding into space.

- Decide how deep you want your object to be. Draw a back face parallel to the front face, connecting the perspective lines. The vertical lines of the back face should be vertical, and the horizontal lines should be horizontal. Notice how this back face appears smaller than the front face? That's perspective affecting scale.

- Erase any extra perspective lines extending beyond the back face. Voila! You have a box in one-point perspective.

What if the object is above the horizon line? Same process, but the perspective lines will go down to the VP. Imagine looking up at the bottom of a floating box – the lines go down. What if it's on the horizon line? The lines above the HL go down, and the lines below the HL go up.

Grab your pencil right now and try drawing a simple box using these steps! It's the best way to make it click. Once you've got the box down, try applying it to something like a hallway or a simple room interior.

Applying One-Point Perspective to Everyday Objects & Spaces

Let's move beyond the basic box and try something you see every day: a door or a window, or even a room.

Drawing a Door or Window:

- Start with your Horizon Line (HL) and Vanishing Point (VP) on it.

- Draw the front face of the door or window as a rectangle. Since you're looking straight at it, its vertical sides are parallel to the sides of your page, and its horizontal sides are parallel to the top/bottom.

- From the corners of this rectangle, draw light perspective lines back to the VP.

- Decide how deep the door frame or window frame is. Draw a second rectangle inside the first one, connecting the perspective lines. This represents the back edge of the frame. Again, notice how the back rectangle is smaller, demonstrating the effect of distance on scale.

- Erase extra lines. You've just drawn a door or window in one-point perspective!

Drawing a Simple Room Interior:

- Draw your Horizon Line (HL) and place your Vanishing Point (VP) on it (often in the center for a head-on view).

- Draw the back wall of the room as a large rectangle or square around the VP. The edges of this rectangle should be parallel to the edges of your page.

- From the four corners of the back wall, draw light perspective lines extending outwards towards the edges of your page. These lines represent the edges where the back wall meets the floor, ceiling, and side walls.

- Decide where the side walls, floor, and ceiling end (i.e., where they meet the front of your imaginary picture plane). Draw lines parallel to the edges of your page to define these boundaries. The line for the floor will be horizontal, the line for the ceiling will be horizontal, and the lines for the side walls will be vertical.

- Erase the perspective lines that extend beyond these boundaries. You now have a basic room in one-point perspective!

See? It's the same principle as the box, just applied to different shapes and spaces. It's incredibly effective for creating a sense of depth quickly. Ready to add another dimension?

Two-Point Perspective: Seeing Objects from an Angle

Once you're comfortable with one-point, two-point perspective is the next step. It's used when you're looking at an object from a corner, so you see two faces receding away from you. This requires two vanishing points, both located on the horizon line.

Think of looking at the corner of a building or a table from an angle. The lines of the building or table that are parallel in reality will converge to one of the two vanishing points. I remember trying to draw my wonky desk from an angle, and it looked like a funhouse mirror until I finally understood that all the lines going in one direction had to meet at VP1, and all the lines going in the other direction had to meet at VP2. It was a lightbulb moment! This is also where foreshortening becomes more apparent – lines and shapes viewed at a sharp angle away from you will appear compressed. Foreshortening is the visual effect that causes an object or distance to appear shorter than it actually is because it is angled sharply towards or away from the viewer.

Here's how to approach it:

- Draw your horizon line.

- Place two vanishing points (VP1 and VP2) on the horizon line, usually far apart towards the edges of your page. How far apart? Generally, the further apart they are, the less distorted your drawing will look, especially near the center. Placing them off the page entirely can give a more natural look for wider scenes. This relates to your cone of vision; placing VPs too close together forces objects near the edges of your drawing outside a natural field of view, causing distortion, like looking through a narrow tube.

- Draw a single vertical line somewhere on your page. This line represents the closest vertical edge of your object (like the corner of a building). If the object is below the HL, the line will be below it. If it's above, the line will be above. If it crosses the HL, the line will cross it.

- From the top and bottom of this vertical line, draw light perspective lines extending to both VP1 and VP2. These lines define the top and bottom edges of the two visible faces of your object as they recede. Notice how these lines angle towards the VPs, showing how the object shrinks in apparent scale as it moves away from you.

- Decide how wide you want each visible face to be. Draw new vertical lines between the perspective lines, parallel to your initial vertical line. These mark the far edges of the visible faces. Again, these vertical lines will appear shorter the further they are from your initial line, illustrating the effect of distance on scale.

- From the tops of these new vertical lines, draw perspective lines back to the opposite vanishing point (from the left new line to VP2, from the right new line to VP1). Where these lines intersect is the far corner of your object.

- Erase extra perspective lines. You now have an object in two-point perspective!

It sounds more complicated than one-point, but it's just adding one more vanishing point and thinking about which lines go to which VP. Try drawing a simple box or a book using these steps! You'll start to see how proportion is maintained relative to the perspective grid.

Drawing a Table in Two-Point Perspective

Let's apply this to something a bit more complex, like a table. This is where understanding how objects relate to the HL is key.

- Draw your HL and VP1 and VP2.

- Since you're likely looking down at a table (a Bird's-Eye View), draw your initial vertical line (the closest corner leg) below the horizon line.

- From the top and bottom of this line, draw perspective lines to both VP1 and VP2. These lines will go up towards the HL.

- Draw the other three legs of the table using vertical lines, making sure they are parallel to your first leg and fall within the perspective lines you drew. Remember, legs further away will appear shorter – this is scale in action.

- Now, for the tabletop. From the top of each leg, draw perspective lines to the appropriate vanishing points to define the edges of the tabletop. The lines going in one direction go to VP1, and the lines going in the other direction go to VP2. Pay attention to how the tabletop might appear compressed depending on your angle – that's foreshortening.

- Connect the lines to form the tabletop. Erase any hidden lines.

Drawing furniture like tables and chairs is fantastic practice for two-point perspective because you have multiple elements (legs, seat, back) that all need to align with the same vanishing points. It really helps solidify the concept. What about looking up or down at something really tall?

A Glimpse at Three-Point Perspective

This is where things get a bit more dynamic. Three-point perspective is used when you're looking up or down at a tall object, like a skyscraper. In addition to the two vanishing points on the horizon line (for the receding horizontal lines), there's a third vanishing point either far above (looking up - Worm's-Eye View) or far below (looking down - Bird's-Eye View) the horizon line. All vertical lines converge to this third VP. Why? Because you are no longer viewing them parallel to the picture plane, but from an angle that makes them appear to recede upwards or downwards, just like horizontal lines recede left or right. This is another form of foreshortening, applied to vertical elements.

It's less common for simple objects on a table, but essential for drawing buildings from a worm's-eye or bird's-eye view. For beginners, just understanding when it's used is a great start – when your vertical lines aren't parallel to the page edges anymore. Beyond this, there are even more complex systems like multi-point or curvilinear perspective, but we'll save those for another day!

Atmospheric Perspective: The Other Kind of Depth

But wait, there's another way the world tricks your eye into seeing depth! While linear perspective (one, two, three-point) deals with how lines converge, atmospheric perspective is about how the atmosphere affects the appearance of objects as they recede into the distance. Think of mountains far away – they look lighter, bluer, and less detailed than mountains close up. This happens because of dust and moisture in the air scattering light.

Artists have used this for centuries! Leonardo da Vinci, for example, wrote about how colors become less saturated and forms less distinct in the distance. In drawing, you can use this effect to enhance the illusion of depth: make distant objects lighter, less saturated in color, and less sharp than objects in the foreground. It's a powerful tool to combine with linear perspective.

Beyond the Box: Perspective for Organic Shapes and Figures

Okay, so boxes and furniture are great for learning, but what about people or trees? You don't draw perspective lines on a figure, but you use perspective to place the figure correctly in space. Imagine the figure standing inside a transparent box. Draw the box in perspective, then draw the figure within those boundaries. This helps ensure they are the right size and in the correct position relative to other objects and the environment. This is where understanding scale and proportion is vital – a figure further away needs to be drawn smaller, and perspective helps you determine how much smaller based on its position relative to the HL and VPs.

Similarly, for organic shapes like trees or hills, you can imagine simple geometric forms (cylinders, spheres, cubes) that approximate their volume and use perspective to place and size those forms correctly. Then, draw the organic shape around the underlying perspective structure. You can also use central axes or contour lines that follow the perspective flow to help define the form in space.

Tips for Organic Shapes and Figures:

- Think in simple forms: Break down complex shapes into basic boxes, cylinders, or spheres first.

- Place the bounding box: Draw a perspective box that the figure or object fits inside to get the scale and position right.

- Use central axes: For figures or cylindrical objects, draw a central line that follows the perspective back to the VP.

- Contour lines: Use lines that wrap around the form and follow the perspective to show its volume in space.

- Observe references: Look closely at how figures and organic shapes appear in photos taken from different angles and distances.

Common Perspective Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

We've all been there! Don't feel bad if you do this. We all make mistakes when learning something new. Perspective is no different! Here are a few common ones I've seen (and definitely made myself!):

- Not Using a Horizon Line: Trying to eyeball perspective without establishing your eye level first is like trying to navigate without a compass. Always start with your HL. Why? Because the HL is your eye level, the fundamental reference point for how everything else in the scene relates to you. Without it, your sense of space will feel arbitrary and disconnected.

- Vanishing Points Not on the HL: Remember, VPs for linear perspective must sit on the horizon line. If they're floating above or below, your perspective will be off. Why? Because vanishing points are defined as the points on the horizon line where parallel lines appear to meet. They are intrinsically linked to your eye level. If they aren't on the HL, your ground plane will look tilted or warped.

- Parallel Lines Not Going to the Same VP: In one-point, all receding parallel lines go to the single VP. In two-point, all parallel lines in one direction go to VP1, and all parallel lines in the other direction go to VP2. Don't let them wander to different points! Why? Because that's the core principle of linear perspective – parallel lines converge to a single point. If they go to different points, the object will look twisted or broken.

- Vertical Lines Not Vertical (in One/Two-Point): Unless you're using three-point perspective, vertical lines (like the corners of a box or building) should be parallel to the sides of your page. Why? Because in one and two-point perspective, you are viewing the scene such that vertical lines are parallel to your picture plane. If they aren't vertical, your objects will look like they're leaning or falling over.

- Drawing Objects Above/Below HL Incorrectly: Remember, lines from objects below the HL go up to the VP, and lines from objects above the HL go down to the VP. Imagine looking down at the top of a box on the floor – the lines go up. Why? Because the VP is on your eye level (HL). Lines from objects below your eye level must angle upwards to reach it, and lines from objects above your eye level must angle downwards. Getting this wrong makes objects look like they're floating or sinking.

- Drawing Circles as Circles in Perspective: A circle viewed from an angle in perspective appears as an ellipse. Only a circle viewed perfectly head-on (parallel to the picture plane) will appear as a true circle. Why? Because of foreshortening – the circle is compressed along the axis receding into space. The major axis of the ellipse will be perpendicular to the direction receding to the VP, and the minor axis will align with that direction.

The key is practice and observation. Look at the world around you! See how lines converge. Using reference photos can be incredibly helpful here – try identifying the Horizon Line and Vanishing Points in a photo before you start drawing.

Quick Tips for Getting Started

Here are a few things to keep in mind as you practice:

- Always start with the Horizon Line. Seriously, it's your anchor.

- Draw lightly at first. Your perspective lines are guides; you'll erase them later.

- Practice simple shapes. Boxes, cubes, and cylinders are your best friends for learning the basics.

- Use a ruler initially. It helps train your eye to see straight lines converging correctly. You can loosen up later.

- Observe the real world. Look at rooms, buildings, streets, and how things change size and shape with distance.

- Don't aim for perfection. Aim for understanding the principles. Your first attempts will be wonky, and that's okay!

Practice Makes... Less Wonky

Ready to get your hands dirty? The best way to get a handle on perspective is to just start drawing. Don't aim for perfection, aim for understanding. Here are some ideas:

- Draw Simple Boxes: Start with boxes in one-point and two-point perspective, placing them above, below, and on the horizon line.

- Draw Everyday Objects: Try drawing a simple book, a mug, or a chair using the 1-point or 2-point methods you learned.

- Draw Rooms: Pick a corner of a room and draw it in one-point perspective (if looking straight at a wall) or two-point (if looking at a corner). Pay attention to how the lines of the floor, ceiling, and walls converge.

- Draw Streets: Find a photo of a straight street or railway tracks and try to draw it using one-point perspective. For a street corner, use two-point.

- Use a Grid System: For more complex scenes or to ensure accuracy, try drawing a simple grid in perspective (using your HL and VPs) and then sketching your objects within the grid squares. This can help you place elements correctly and maintain relative scale.

- Use a Ruler (at first): It's okay to use a ruler when you're learning! It helps train your eye. Eventually, you'll be able to sketch perspective more freely.

Don't be afraid to mess up! Every wobbly line is a step towards understanding. And hey, if you're feeling brave, share your practice drawings online – seeing others' attempts and getting feedback can be super motivating!

Perspective and Composition: Guiding the Eye

Perspective isn't just a technical skill; it's a powerful compositional tool. The converging lines naturally lead the viewer's eye towards the vanishing point. You can use this to direct attention to a specific area of your drawing, create a sense of vastness, or make a scene feel more dynamic.

Atmospheric perspective also plays a role, creating a sense of depth that can separate foreground elements from the background, adding layers to your composition. Understanding these tools allows you to not just draw what you see, but to guide how the viewer sees it.

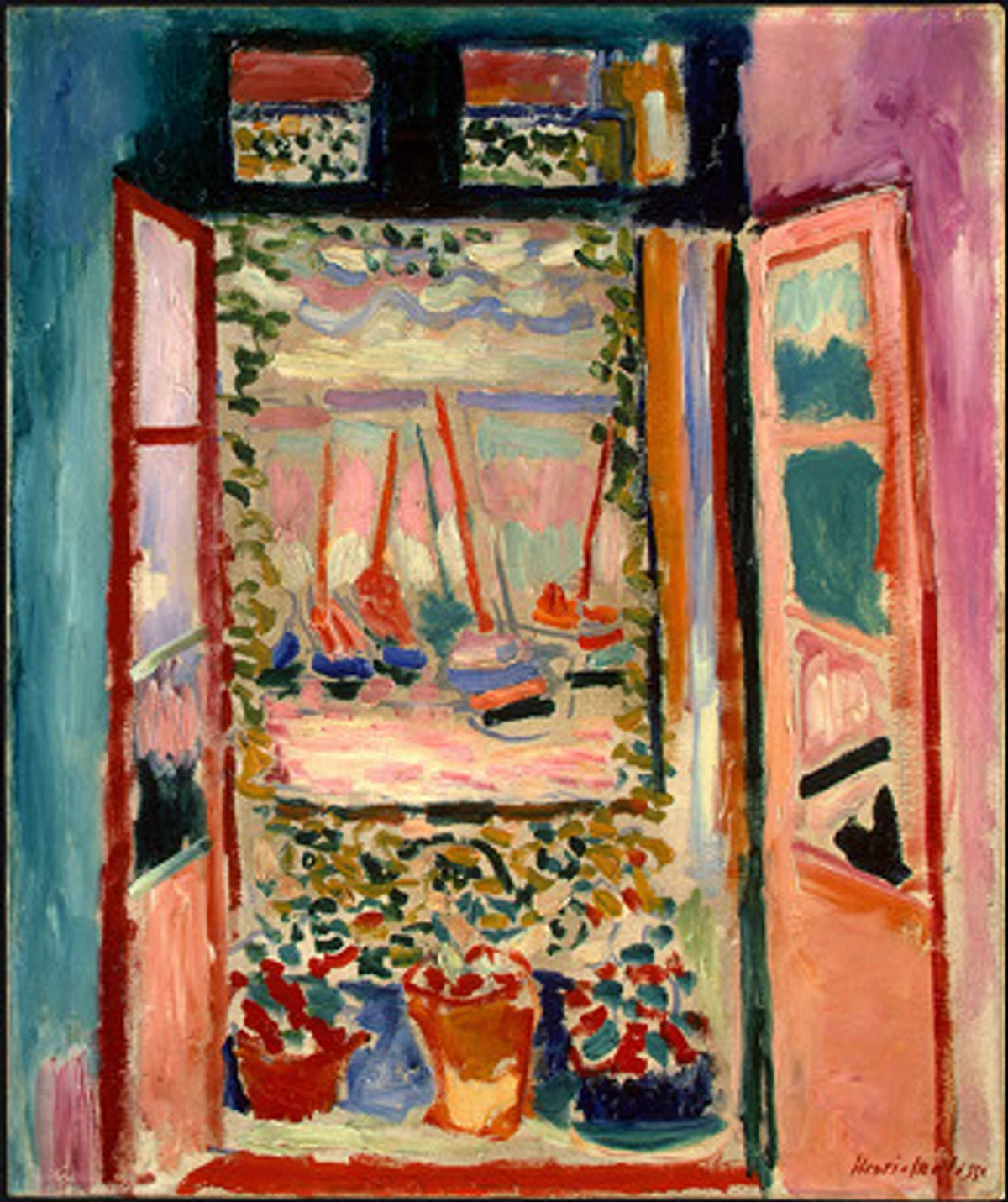

Perspective in Abstract Art

Even in abstract art, where realistic representation isn't the goal, the underlying principles of perspective can be incredibly useful. Understanding how lines imply direction, how shapes relate to each other in space, and how the illusion of depth can be created (or intentionally flattened) informs compositional choices. For example, using converging lines can still create a sense of movement or focus, even if those lines don't represent a physical object. Playing with scale and overlapping shapes, informed by how perspective works in the real world, can create visual tension or harmony. Atmospheric perspective, too, can be translated into abstract terms by varying color intensity and edge sharpness to suggest layers or distance, even in non-representational forms. It's about using the language of perspective to build a compelling visual experience, rather than strictly adhering to its rules for realism. My own abstract work often plays with implied depth and spatial relationships, drawing on this understanding (Art for sale).

Summary of Key Perspective Concepts

Concept | Definition | When to Use | Key Feature | Visual Cue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizon Line (HL) | Your eye level in the drawing. | Always, as the base for all linear perspective. | Horizontal line, position depends on viewer height. | A horizontal line across the page. |

| Vanishing Point(s) (VP) | Point(s) on the HL where parallel lines appear to converge. | For linear perspective (one, two, or three-point). | Located on the Horizon Line (except 3rd VP). | Lines appear to meet at this point. |

| Picture Plane | The imaginary window through which you view the scene. | Conceptual tool to understand how 3D space is projected onto a 2D surface. | Your drawing surface. | Your paper/canvas. |

| Scale | The size of an object relative to other objects or the environment. | When placing objects correctly in space. | Objects appear smaller as they recede. | Objects get smaller further from the viewer. |

| Proportion | The size of parts of an object relative to the whole. | When placing objects correctly in space. | Maintained relative to perspective grid. | Parts of an object stay in correct relation. |

| Foreshortening | How objects or parts of objects appear compressed when viewed head-on or at a sharp angle. | When drawing objects or figures at sharp angles receding from the viewer. | Apparent shortening of forms. | Shapes look squashed or shortened. |

| Cone of Vision | The area within which objects appear undistorted; related to VP placement. | When deciding how far apart to place VPs in two-point perspective. | VPs too close cause distortion at edges. | The natural field of view you're drawing. |

| One-Point Perspective | Drawing objects with one face parallel to the viewer. | Looking straight at a wall, road, or front of an object. | Single VP on the HL. | One point on the HL where lines meet. |

| Two-Point Perspective | Drawing objects seen from a corner. | Looking at the corner of a building, box, or furniture. | Two VPs on the HL. | Two points on the HL where different lines meet. |

| Three-Point Perspective | Drawing tall objects seen from a high or low angle. | Looking up at a skyscraper or down from a cliff. | Two VPs on HL, one third VP above/below HL. | Vertical lines also converge. |

| Atmospheric Perspective | How the atmosphere affects object appearance over distance. | To enhance depth and realism in landscapes and scenes with distance. | Distant objects are lighter, bluer, less detailed. | Objects fade and lose detail in the distance. |

Wrapping Up: Just Start Drawing!

Learning perspective can feel like a hurdle, but it's one that unlocks so much potential in your art. It's not about making everything look like a photograph; it's about giving your drawings a believable structure, a sense of place, and guiding the viewer's eye. It's a fundamental skill, much like understanding (Art Genres Explained: A Personal Guide Through the Art Maze) or the (Elements of Art Explained: Your Ultimate Guide to Seeing Like an Artist) themselves.

Don't worry about getting it perfect right away. Grab a pencil, a ruler (or not!), and just start experimenting. Draw those wonky tables, then try drawing them with a horizon line and a vanishing point. See what happens. Observe the world around you. The more you practice, the more intuitive it will become.

And remember, even in the most abstract pieces, the underlying principles of space and form, hinted at by perspective, can add a layer of depth and intention. It's all part of the journey of seeing and creating like an artist (Artist's journey/timeline). If you're curious about my own journey or my abstract work, feel free to explore my (Art for sale) or learn about my museum in Den Bosch (Artist's museum ('s-Hertogenbosch, NL)).