Mexican Muralism: Art, Revolution, and National Identity (Ultimate Guide)

Explore Mexican Muralism, a monumental art movement that shaped a nation. This ultimate guide delves into its historical context, key artists like Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros, their groundbreaking techniques, and its enduring impact on public art and identity, including the vital role of women muralists and critical perspectives.

Mexican Muralism: Art, Revolution, and National Identity

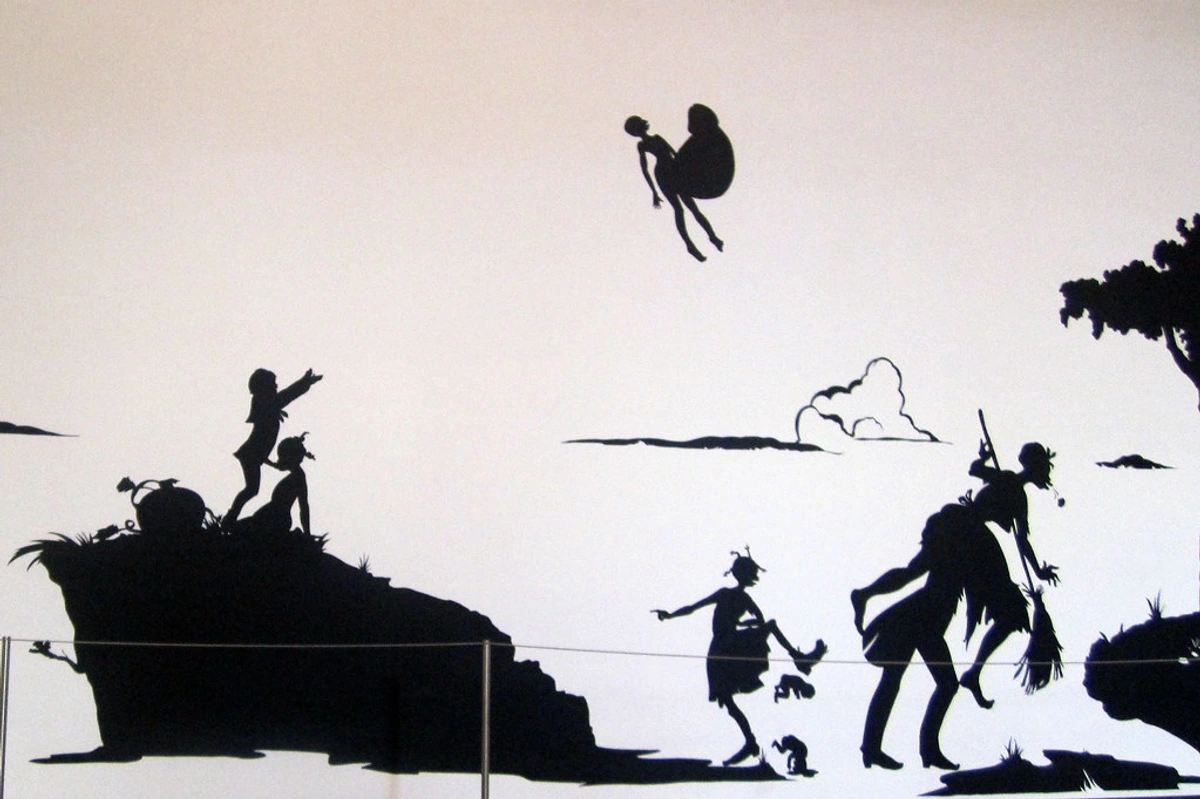

Mexican Muralism represents a monumental artistic movement that arose from the profound societal upheaval of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). It was conceived not for exclusive galleries, but for the expansive walls of public buildings, transforming them into colossal canvases for social reform, public education, and the forging of a distinctive national identity. This movement stands as a pivotal chapter in the broader art history eras, powerfully illustrating how art can serve as a profound catalyst for social change. The murals provided a visual narrative of a nation in the throes of redefining itself, actively challenging colonial narratives and constructing a unique post-revolutionary identity. This exploration provides a comprehensive examination of the movement's historical context, its principal figures, their distinct styles and innovative techniques, and the enduring legacy of this profoundly impactful era in art.

Forging a Nation: The Post-Revolutionary Canvas

Prior to the vibrant emergence of muralism, Mexico's artistic landscape was largely shaped by European academic styles, a lingering vestige of the Porfiriato era. This period, while introducing certain aspects of modernization, frequently marginalized or suppressed the rich tapestry of indigenous Mexican culture and artistic traditions. One observes a quiet adherence to portraiture, landscapes, and allegorical scenes that often mirrored Parisian salons, rather than reflecting the unique struggles and profound heritage of the Mexican people. The Mexican Revolution, a decade-long crucible of conflict, fundamentally reshaped the nation, leaving behind a populace yearning for a unified identity and a narrative that honored their indigenous roots, acknowledged their struggles, and articulated their aspirations for a more equitable future. This tumultuous period cultivated a fertile ground where art could truly blossom as an indispensable tool for national reconstruction.

In this pivotal moment, José Vasconcelos, then-Minister of Public Education, played a transformative role. A visionary intellectual, Vasconcelos grasped the immense power of art to educate and inspire a largely illiterate population. He initiated extensive commissions for artists to paint murals on government buildings, schools, and other public spaces. His conviction was that these monumental works could effectively narrate the story of Mexico – encompassing its ancient past, its colonial oppression, its revolutionary struggle, and its vision for a more socialist future. His educational objectives were clear: to foster literacy, promote Mexican cultural values, and seamlessly integrate the indigenous past into a modern national consciousness. This initiative represented a direct, unfiltered form of public art, functioning as a visual history book accessible to the masses.

Beyond Vasconcelos, other influential voices contributed significantly to the intellectual currents that made muralism possible. Figures such as the artist and theorist Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo) fervently championed a national art form deeply rooted in Mexican landscape and culture, even venturing into his own unique geological painting that depicted Mexico's volcanic grandeur. Artists like Alfredo Ramos Martínez, renowned for his innovative open-air art schools, and Saturnino Herrán, who skillfully incorporated Mexican folk traditions and indigenous themes into his canvases, laid crucial groundwork. Herrán, in particular, blended European Symbolism with vivid depictions of Mexican life and spirituality, foreshadowing the grand narratives of the muralists. These early pioneers cultivated an environment ripe for artistic revolution, preparing the national psyche for the monumental scale and didactic purpose that muralism would embody.

Los Tres Grandes: The Revolutionary Pillars

At the very epicenter of this artistic renaissance stood "Los Tres Grandes" (The Big Three): Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Each artist brought a distinct vision, stylistic approach, and ideological conviction to the movement, collectively shaping its powerful and often contentious legacy. The convergence of such disparate personalities on a monumental task underscores their shared passion for their nation's future, despite their individual artistic and political divergences.

Diego Rivera: The Epic Narrator of History

Perhaps the most internationally celebrated of the muralists, Diego Rivera (1886–1957) was a master storyteller with a brush. His work, frequently characterized by its vibrant colors, rich details, and sweeping historical narratives, aimed to celebrate Mexico's indigenous heritage, glorify its revolutionary heroes, and critique the injustices inherent in capitalism. Rivera meticulously championed specific symbols and narratives, bringing to life vivid depictions of pre-Hispanic markets, ancient rituals, and the revered feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, on public walls. This represented a deliberate and powerful reclaiming of identity, a visual declaration that Mexico's true roots lay far deeper than any colonial veneer. Rivera's distinctive brand of social realism blended monumental compositions with a folk art sensibility, making complex historical and political messages accessible.

Rivera's artistic journey began in Europe, where he absorbed cubist influences, evident in the geometric forms and fragmented perspectives of his early works. However, he famously returned to Mexico with the explicit intention of forging a uniquely national style. For a deeper understanding of his influential career, one might consider exploring understanding influential artists like Diego Rivera.

His colossal murals at the National Palace in Mexico City, which meticulously depict the history of Mexico from ancient civilizations to the post-revolutionary era, stand as monumental examples of historical narrative through art. Rivera, despite his profound celebration of Mexican life, was also a formidable critic. His works subtly, and at times overtly, depicted the encroachment of foreign capital, the dehumanizing aspects of unchecked industrialism, and the struggles of the working class. His vision of a "socialist future" often portrayed agricultural workers in harmonious, almost idyllic settings, celebrating communal labor and land reform – a deeply Mexican vision of progress built on the dignity of every person's work.

One of his most famous controversial works, Man at the Crossroads, originally commissioned for Rockefeller Center in New York, was destroyed due to its inclusion of a portrait of Vladimir Lenin, a choice that starkly highlighted the political tensions of the era. Rivera later recreated this powerful statement as Man, Controller of the Universe at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. His frescoes at the Ministry of Public Education similarly narrate the daily lives of workers and peasants, glorifying their labor and challenging capitalist hierarchies.

José Clemente Orozco: The Revolutionary's Anguish

While Rivera often presented an idealized vision, José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) offered a far more visceral, even tormented, perspective on Mexico's soul. Orozco's murals are characterized by their dramatic, often anguished figures, stark compositions, and a profound sense of human suffering. He was a searing critic of all forms of oppression and depicted the brutal costs of revolution, the hypocrisy of leaders, and the enduring pain of humanity. His style, often described as expressionistic, utilized bold lines, deep shadows, and fragmented forms to evoke intense emotion and a sense of tragedy. Orozco's critiques were rarely subtle; he laid bare the raw wounds of revolution, the corruption that could plague any power structure (including the post-revolutionary government), and the eternal cycle of human suffering, steadfastly refusing to prettify the past or present. His works resonate deeply with the themes explored in the ultimate guide to expressionism.

His masterpiece, The Epic of American Civilization, located at Dartmouth College in the United States, stands as a testament to his critical worldview, portraying indigenous civilizations, the brutal impact of colonialism, and the often dehumanizing aspects of industrial modernism with unflinching honesty. This work garnered significant attention for its provocative themes and stark imagery, challenging established narratives of American history. Murals like La Trinchera (The Trench), found at the Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara, viscerally convey the human toll of conflict through its dynamic composition and powerful, almost sculptural figures. In contrast, Maternidad (Maternity) subtly weaves in themes of hope amidst struggle, a delicate balance within his often somber palette, highlighting the enduring human spirit.

David Alfaro Siqueiros: The Innovator and Activist

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974) was the radical experimenter of the group, perpetually pushing the boundaries of artistic technique and form. A fervent communist and lifelong political activist, Siqueiros viewed art as a direct weapon for revolution and social transformation. He not only painted but almost literally charged his murals with political fire. These were not subtle nudges; they were visual manifestos, direct calls to action against injustice, sometimes even critiquing the very government that commissioned them – a brave, almost audacious move. His dynamic, often sculptural murals employed unconventional materials and pioneering techniques, striving for a powerful sense of movement and mass participation. Siqueiros's deep involvement in political struggles, including his participation in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, directly informed the aggressive energy and revolutionary fervor evident in his art.

His most ambitious work, the Polyforum Siqueiros in Mexico City, is a dodecahedron-shaped building entirely covered in murals both inside and out, creating an immersive, multi-sensory experience designed to fully envelop the viewer in his narrative of human liberation. Siqueiros's New Democracy mural at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, with its powerful portrayal of a woman breaking free from chains, exemplifies his revolutionary fervor and commitment to social justice. His pioneering work continues to influence contemporary street art movements and powerfully exemplifies art as a catalyst for social change.

Comparing the "Big Three"

To better understand their individual contributions and nuanced approaches, here is a comparative overview of Los Tres Grandes, highlighting their distinct artistic voices even within a shared revolutionary movement:

Artist | Primary Focus/Themes | Distinctive Style | Philosophical/Political Stance | Key Locations & Notable Works |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diego Rivera | Mexican history, indigenous culture, pre-Hispanic life, industrialism, socialist ideals, celebrating labor, agrarian reform. | Rich colors, detailed narratives, often depicting harmonious collective life, historical scope, folk art sensibility. | Committed Communist, celebrated indigenous identity and Marxist ideals. | National Palace, Ministry of Public Education, Palacio de Bellas Artes (Man, Controller of the Universe) (Mexico City), Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit Industry Murals). |

| José Clemente Orozco | Human suffering, costs of revolution, social injustice, individual struggle, critique of power and corruption, universal human condition. | Dramatic, expressionistic, dark palette, tormented figures, intense emotion, stark compositions, fragmented forms. | Anarchist leanings, deeply critical of all forms of tyranny, including post-revolutionary hypocrisy. | Palacio de Bellas Artes, Hospicio Cabañas (Guadalajara), Dartmouth College (The Epic of American Civilization) (USA). |

| David Alfaro Siqueiros | Revolutionary struggle, future, technology, mass movements, political activism, social realism with a modern edge, human liberation. | Dynamic, experimental techniques (pyroxylin, airbrush, photography), sculptural, sense of movement, bold, often aggressive forms, multi-angled perspectives, poliforum. | Militant Communist, saw art as a direct weapon for political action and social engineering. | Polyforum Siqueiros, Palacio de Bellas Artes (New Democracy) (Mexico City), UNAM Rectorate Tower. |

Beyond Los Tres Grandes: Diversifying Voices and Evolving Perspectives

While "Los Tres Grandes" undeniably dominate the narrative, it is crucial to acknowledge the contributions of other significant artists and the evolving nature of Mexican muralism. The movement was not exclusively male-dominated; pioneering women artists also left an indelible mark, often navigating additional challenges posed by prevailing societal norms.

The Role of Women in Mexican Muralism

Though often overshadowed, women played vital and multifaceted roles as artists, collaborators, and muses within the muralist movement. Aurora Reyes (1908–1996) holds the significant distinction of being Mexico's first female muralist, creating powerful works like Atentado a las Maestras Rurales (Attack on the Rural Teachers) in the Centro Escolar Revolución. Her murals depicted poignant scenes of social injustice, celebrated education, and championed the rights of women and indigenous communities, broadening the thematic scope of the movement beyond the prevailing masculine narratives. Other notable figures include Elena Huerta (1908–1997), known for her evocative murals in Nuevo León that often depicted regional history and labor struggles, and Rina Lazo (1923–2014), who served as Diego Rivera's highly capable assistant for many years before creating her own significant murals, such as Venceremos (We Will Win) and her work at the National Museum of Anthropology. These women used the monumental mural format to advocate passionately for social justice, women's rights, and indigenous causes, demonstrating remarkable resilience and artistic prowess in a challenging environment. The additional hurdles faced by women artists in gaining recognition and commissions make their contributions all the more remarkable, forcing one to reflect on the systemic biases of the era.

Evolution and Diversification of Styles

As the initial golden age of Los Tres Grandes began to wane, newer artistic currents emerged, and the strict adherence to overt social realism started to diversify. Artists like Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991), while profoundly influenced by the scale and public ambition of the muralists, consciously diverged from their overtly political and didactic approach, exploring a more abstract and modernist style. Tamayo's work often incorporated pre-Hispanic motifs and a distinctly Mexican color palette but prioritized universal themes, painterly concerns, and a less overt narrative over explicit revolutionary propaganda. His contributions, like Nacimiento de la Nacionalidad (Birth of Nationality) at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, demonstrate a different path within Mexican public art, one that moved towards a more symbolic, poetic, and introspective engagement with national identity, offering a sophisticated counterpoint to the more literal narratives of his predecessors.

Other notable muralists, such as Roberto Montenegro (1887–1968), who painted allegorical works in public buildings, and Jorge González Camarena (1908–1980), known for his dynamic, often three-dimensional murals like La Liberación (The Liberation) at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, further expanded the visual and thematic vocabulary of Mexican muralism, ensuring its continued vitality and evolution.

Techniques & Innovation: The Muralists' Craft

The monumental scale and inherently public nature of Mexican Muralism necessitated specific artistic techniques that ensured both durability and widespread impact. The artists predominantly revived and adapted the ancient art of fresco painting, a labor-intensive technique involving the application of pigments suspended in water onto freshly applied, wet lime plaster. This method allowed for the immense scale required for public buildings because the pigments chemically bind with the plaster as it dries, creating an incredibly durable and integrated artwork that is resistant to the elements. Understanding traditional fresco painting techniques provides crucial context for their technical achievements.

However, the muralists, particularly Siqueiros, were not content with just traditional fresco. They tirelessly pushed the boundaries of artistic practice, experimenting with a range of modern industrial materials and innovative techniques. Siqueiros famously embraced pyroxylin (a type of cellulose nitrate enamel or lacquer, often used for automobiles and industrial finishes) for its quick-drying properties, vibrant sheen, and durability, as explored in articles like the history of acrylic painting from industrial innovation to artistic medium. He also incorporated advanced techniques like airbrushing, photography, and film projections to achieve dynamic compositions and precise transfers. His pursuit of poliforum (multi-angled) viewing experiences, designing murals to be seen from various perspectives, further exemplifies his relentless drive for innovation.

These technical innovations were driven by a desire to achieve dynamic, industrial textures, to speed up the process for large-scale works, and to create a more lasting, almost sculptural effect that resonated with the modernity and urgency of the revolution. Siqueiros firmly believed that these modern materials offered greater durability and a more contemporary aesthetic, perfectly suited for the revolutionary message. Other artists also explored materials beyond traditional fresco, including encaustic, tempera, oil paints, mosaics, and carved stone, further expanding the movement's material vocabulary and pushing the artistic possibilities of public art.

Legacy and Global Echoes

Mexican Muralism transcended its national borders, profoundly inspiring artists and art movements across Latin America and the United States. Its unwavering commitment to social realism, public education, and political engagement resonated deeply during times of global economic hardship and pervasive social upheaval. In the United States, for instance, the movement significantly influenced the New Deal art projects during the Great Depression. American artists like Thomas Hart Benton and programs such as the WPA Federal Art Project clearly drew inspiration from Mexico's public art initiatives. Murals such as Benton's America Today series or the numerous public works funded by the WPA echoed the Mexican muralists' dedication to depicting the lives of ordinary people, laborers, and the historical narratives of the nation.

Rivera's controversial mural for Rockefeller Center, though ultimately destroyed, also sparked crucial critical debates in the US about artistic freedom and the intersection of political content with public art, highlighting the profound impact Mexican artists had on the American art scene. Later, the Chicano Art Movement in the United States, particularly from the 1960s onwards, drew direct and explicit inspiration from Mexican Muralism. Chicano artists used murals in communities across the American Southwest to express cultural pride, advocate for civil rights, and narrate their own histories of struggle and identity, directly channeling the spirit and revolutionary fervor of their Mexican predecessors, demonstrating the impact of public murals on urban identity.

Like all grand movements, Mexican Muralism eventually saw its most prolific golden age wane. New artistic currents emerged, aesthetic tastes shifted, and inevitably, the titans – Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros – passed on. The political landscape also evolved; the fervent post-revolutionary zeal matured into different national priorities, leading to less direct government patronage for large-scale, overtly didactic murals. Yet, to describe this as a 'decline' would be an oversimplification. It was more a transformation, a quiet assimilation of its powerful lessons into the broader stream of art history. The murals remain powerful symbols of Mexico's journey, serving as a constant reminder of the intertwined relationship between art, politics, and the people. These works have also inspired countless contemporary street art movements and continue to inform how public spaces can be utilized for artistic expression and poignant social commentary.

One common interpretation often encountered is the idea that because the government commissioned these murals, they were simply tools of propaganda. This perspective, however, oversimplifies a complex dynamic. While the state certainly had an agenda to foster a unified national identity and promote its ideals, artists like Orozco, and even Rivera and Siqueiros at times, frequently pushed back against strict mandates, using the walls to critique corruption, express their own, sometimes dissenting, views, or explore the universal struggles of humanity. It represented a delicate, often tense, dance between state patronage and artistic integrity, where the artists often found ways to imbue their work with personal and critical layers that transcended mere propaganda. Today, these breathtaking works can be experienced in many of Mexico City's most significant buildings, forming an integral part of exploring Mexico City's vibrant art scene, and in various locations across Mexico and the United States.

Critiques and Challenges Faced by Mexican Muralism

While celebrated for its monumental achievements, Mexican Muralism was not without its critics and inherent challenges. From its inception, the movement faced scrutiny from various angles:

- Charges of Propaganda: As discussed, the state's patronage led to accusations that the murals served purely as government propaganda, undermining their artistic autonomy. While artists often injected personal critique, the didactic nature and scale sometimes blurred the lines between art and official message.

- Accessibility and Audience: Despite the aim to educate the illiterate masses, some critics argued that the complex iconography and allegorical narratives were not always readily comprehensible to the common viewer, potentially limiting their educational impact.

- Artistic Restrictions: Government commissions, while providing funding and walls, sometimes came with political pressures or thematic restrictions, leading to creative compromises for the artists. Rivera's Man at the Crossroads incident is a prime example of such conflicts.

- Exclusion of Other Artistic Expressions: The dominance of muralism, particularly by Los Tres Grandes, often overshadowed other contemporary artistic forms and movements within Mexico, leading to debates about artistic pluralism.

- Gender Dynamics: The movement was notably male-dominated, with women muralists facing significant barriers to gaining commissions, recognition, and equal standing. The art historical canon has only recently begun to fully acknowledge the vital contributions of figures like Aurora Reyes and Elena Huerta, highlighting historical gender biases.

- Longevity and Conservation: The outdoor and public nature of many murals, coupled with experimental materials like pyroxylin, posed significant challenges for preservation. Environmental factors, urban pollution, and general wear and tear necessitated ongoing conservation efforts.

These critiques offer a more nuanced understanding of Mexican Muralism, acknowledging its complexities and internal tensions alongside its revolutionary triumphs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What was the primary goal of Mexican Muralism?

The primary goal was to leverage public art as a powerful medium for educating a largely illiterate population about Mexican history, fostering a unified national identity in the aftermath of the revolution, promoting social and political ideals (often socialist), celebrating indigenous culture, and challenging previous colonial narratives. It served as an indispensable tool for nation-building and incisive social commentary.

Who are "Los Tres Grandes" of Mexican Muralism?

"Los Tres Grandes" refers to the three most prominent and profoundly influential artists of the Mexican Muralism movement: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Where can one see Mexican murals today?

Many of the most significant Mexican murals are located in Mexico City, particularly within iconic buildings like the National Palace, Palacio de Bellas Artes, the Ministry of Public Education, the Polyforum Siqueiros, and the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. Significant works can also be found in Guadalajara (notably the Hospicio Cabañas with Orozco's masterpieces) and other Mexican cities, as well as internationally, especially in the United States (e.g., Dartmouth College, Detroit Institute of Arts).

What painting technique was predominantly used?

The traditional technique of fresco painting was predominantly used, involving the application of pigments to wet lime plaster. This method allowed for the creation of large-scale, highly durable works suitable for public buildings. However, avant-garde artists like Siqueiros also extensively experimented with modern industrial paints and techniques, such as pyroxylin (a type of enamel) and airbrushing, to achieve dynamic and enduring effects, pushing the boundaries of the medium.

How did the Mexican Revolution influence the movement?

The Mexican Revolution served as the direct and undeniable catalyst for the movement. It created a profound national imperative for a new narrative and identity, which the post-revolutionary government strategically sought to promote through art. The revolution's core ideals – land reform, social justice, the valorization of indigenous heritage, and anti-imperialism – were central themes directly translated into the murals' content, serving as a visual history and an ideological guide for the newly forged nation.

Did Mexican Muralism influence art outside of Mexico?

Absolutely. Mexican Muralism exerted a significant international impact, particularly in the United States, where it profoundly influenced public art programs like those implemented during the New Deal era (e.g., the WPA Federal Art Project), inspiring prominent artists such as Thomas Hart Benton. Its unwavering commitment to social realism, public engagement, and monumental scale also inspired artists across Latin America and directly influenced the Chicano Art Movement in the US Southwest, which adopted muralism as a potent tool for cultural pride and civil rights advocacy. It unequivocally demonstrated globally that art could be a powerful force for public education and profound social change.

What were the main criticisms or challenges faced by Mexican Muralism?

Mexican Muralism faced various critiques, including charges of being government propaganda, concerns about the accessibility of complex iconography to a largely illiterate public, artistic restrictions imposed by patrons, the overshadowing of other art forms, and significant gender biases that marginalized women muralists. Technical challenges related to the longevity and conservation of public outdoor murals also persisted.

How did gender dynamics affect the participation of women in the muralist movement?

Women muralists faced considerable challenges, including limited access to commissions, less recognition compared to their male counterparts, and societal expectations that often hindered their professional careers. Despite these barriers, figures like Aurora Reyes and Elena Huerta persevered, creating significant works that broadened the thematic scope of muralism to include feminist perspectives and social justice issues often overlooked by their male contemporaries.

What is the difference between Mexican Muralism and other public art movements?

While sharing some commonalities with other public art movements in its use of public space and social commentary, Mexican Muralism is distinguished by its unique historical genesis in the Mexican Revolution, its explicit mission to forge a post-colonial national identity, its strong didactic and often socialist ideological underpinnings, and its revival and innovation of fresco and other industrial painting techniques on a grand governmental scale. Unlike many ephemeral street art movements, it was often state-sponsored and deeply embedded in national reconstruction efforts.

Conclusion

Mexican Muralism stands as an enduring and powerful testament to art's profound ability to shape national consciousness and serve as a commanding voice for social and political transformation. Far from being mere decorative elements, these monumental works transformed public spaces into living history books, challenging, educating, and inspiring generations. The indelible legacy of Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, and their contemporaries continues to resonate globally, reminding contemporary artists and viewers alike of art's immense capacity for dialogue, incisive critique, and lasting impact. This movement exemplifies how artistic vision, when deeply entwined with a nation's historical trajectory, can leave an enduring mark on the world, one magnificent wall at a time. The powerful messages embedded within these murals remain as relevant today as they were a century ago, inviting continued reflection on the intersections of art, history, and society.