The Enduring Magic of Printmaking: A Personal Guide to Techniques, History & Abstract Art

Dive into the captivating world of printmaking with a personal, introspective journey. Explore relief, intaglio, lithography, screenprinting, and collagraphy, uncovering their rich history and unique influence on contemporary abstract art. Discover practical tips, collector insights, and the profound, sometimes chaotic, joy of making an impression.

The Enduring Magic of Printmaking: A Personal Journey Through Techniques and History

There's a certain magic to printmaking, isn't there? It's this beautiful, sometimes infuriating, dance between precision and serendipity, where you commit an image to a matrix—the foundational surface, often a block of wood, a metal plate, or a screen, from which the print is made, essentially the artist's 'master mold'—and then, with a push and a prayer, reveal its existence, often multiple times. It's a bit like life itself: you plan, you execute, and then you hold your breath, hoping for the best, sometimes getting something entirely unexpected but equally profound. I remember once, convinced I'd ruined a woodblock with an overzealous cut, only to find the resulting 'flaw' introduced a dynamic tension I'd been unknowingly striving for. This ancient art form, dating back to early civilizations who sought to multiply images for religious or administrative purposes, still holds a profound place in the modern art world. This enduring appeal isn't just about replication; it's about the unique tactile and visual qualities each technique offers, and the democratic power of making art accessible. Think Mesopotamian cylinder seals, intricately carved to roll impressions onto clay for authenticating documents, marking ownership of goods, or even adorning clothing, acting as both a signature and a symbol of status. Or consider early Chinese seals, used for official decrees, personal identification, and the attribution of artworks, with each impression carrying specific authority or artistic intent. These ancient roots resonate deeply with me, reminding me that even in my most abstract contemporary work, I'm tapping into a lineage of human expression that spans millennia. For me, it was never just about creating an image; it was about the process, the tactile engagement, the smell of ink, the satisfying thwack of the press. It feels ancient and utterly modern simultaneously, a testament to humanity's enduring desire to replicate beauty, or simply to see if a messy idea can manifest tangibly. This article aims to demystify printmaking for both burgeoning artists and seasoned collectors, showcasing its fascinating journey and its deep relevance to contemporary art. In this guide, I'll share my personal journey through the core techniques, their rich historical roots, and how they continue to inspire my own abstract work, offering practical insights and a peek into this captivating craft.

Demystifying Printmaking: More Than Just a Copy

At its heart, printmaking is the art of making multiple original images from a single matrix. Unlike a painting, where each brushstroke creates the final piece, in printmaking, you create a source (the block, plate, screen), and that source is then used to transfer ink onto paper. Think of it like a very artistic stamp, but with infinitely more variables and opportunities for delightful mistakes. Or, if you're like me, opportunities to loudly exclaim, “Well, that’s not what I intended, but it’s… interesting?”

For a long time, I actually thought all prints were just posters. A reproduction, something mass-produced. This is a common misconception! A reproduction is a photographic copy of an existing artwork—think of it as a photograph of a painting. An original print, however, is an artwork conceived and executed by the artist specifically as a print, where the print itself is the original creation. Each one is pulled by hand, often signed and numbered as part of an 'edition' – a predetermined number of identical prints made from a single matrix. These subtle variations make every piece unique yet part of a coherent series; you can often feel the texture of the ink on the paper, a tactile signature of the artist's hand. It's a bit like having siblings: same parents, same DNA, but wildly different personalities and, let’s be honest, often wildly different aesthetics. Why value an original print? Beyond the artist's direct involvement in its creation, it offers a unique aesthetic that mass reproductions can't capture, often carrying a tactile quality and the inherent value of a limited edition. It also offers a deep emotional connection for collectors, a tangible piece of the artist's direct creative process. It's a key distinction, especially for collectors seeking authentic art. Look for unique qualities like a chop mark (an embossed symbol of the artist or print shop), an edition number, or the visible impression of the plate into the paper, known as a plate mark. These physical attributes are often the tell-tale signs of an original print, distinguishing it from a mere copy. Within an edition, you might also encounter Artist's Proofs (APs), reserved for the artist, and Printer's Proofs (PPs), for the master printer. These often hold special value for collectors, sometimes considered as significant as, or even more so than, editioned prints due to their rarity and direct connection to the artist or printer. A typical edition might include 10-20% APs and PPs. These nuanced details are what make original prints, including the abstract pieces you might find in my collection, so special for discerning collectors.

A Brief History of Impressions: Printmaking Through the Ages

The story of printmaking is as old as our desire to communicate and replicate images. From the earliest woodblock prints in ancient China used for textile patterns and religious texts, printmaking quickly evolved as a powerful tool. To truly appreciate this art form, we need to understand its journey through time, a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring power of the reproduced image. This lineage even extends, indirectly, to the later development of photography by establishing the concept of mechanically reproducible images – a precursor to our modern visual world. In fact, one of the earliest known examples of complex printmaking, Ukiyo-e, developed in Japan and revolutionized how art could be consumed, mirroring my own desire to make art accessible and understood.

Japanese Innovation: Ukiyo-e's Collaborative Spirit

Its collaborative nature was key to its success because it allowed for a high degree of specialization and efficient production, thus enabling widespread distribution to a burgeoning middle class. A designer would create the initial drawing, a carver meticulously translated this drawing onto woodblocks (often one for each color), and a printer then applied the inks and pressed the paper to create the final, vibrant image. This division of labor not only allowed for greater artistic quality and intricate detail but also enabled faster production, making art accessible to a wider audience. You can explore its profound global impact in this definitief guide to Ukiyo-e.

The European Renaissance: Disseminating Knowledge and Art

During the Renaissance, printmaking became crucial for disseminating knowledge and art across Europe, truly democratizing visual culture. Artists like Albrecht Dürer, alongside others such as Lucas van Leyden and Marcantonio Raimondi, revolutionized engraving and woodcut, not just by creating intricate images, but by pushing the technical boundaries of the medium, achieving an unprecedented level of detail and realism that spread their fame and influence far beyond their studios and set new standards for graphic arts for centuries. Dürer's meticulous precision always makes me marvel at the sheer dedication and unwavering hand required; it's a level of control I sometimes envy in my own more chaotic, abstract paintings, a fascinating contrast. Prints allowed complex ideas and visual narratives to reach a broader audience than unique paintings ever could, becoming a vital medium for book illustration and the spread of scientific and religious texts, playing a significant role in the Protestant Reformation by rapidly circulating theological arguments and satirical imagery. Historically, many of these early prints were relatively small, designed for book pages or intimate study, a far cry from some of the large-scale installations we see today.

Enlightenment and Revolution: Commentary and Cartography

By the Enlightenment, printmaking, particularly etching and engraving, was instrumental in political caricature and social commentary. Satirical prints could quickly disseminate critiques of power and society, influencing public opinion and even sparking revolutions – consider William Hogarth's moralizing series like "A Rake's Progress," which vividly depicted the social ills of his time, or the precise anatomical plates of Andreas Vesalius, which revolutionized medicine. Moreover, prints played a crucial role in sharing scientific discoveries, anatomical illustrations, and importantly, maps and geographical knowledge, expanding human understanding across continents. Print sizes varied greatly, from small political broadsides to large, detailed maps intended for study, showcasing printmaking's adaptable utility.

The Industrial Age: Mass Production and Artistic Reaffirmation

The Industrial Revolution brought new technologies, leading to mass-produced printed materials and the rise of commercial printing. Innovations like lithography (invented in the late 18th century but gaining prominence in the 19th) and chromolithography allowed for the inexpensive reproduction of color images, fundamentally changing advertising, popular art, and visual culture. Yet, ironically, this era also saw artists reaffirming the unique artistic value of hand-pulled original prints, further solidifying printmaking's place as a fine art, separate from mere commercial reproduction. It’s a fascinating paradox, much like how in our digital age, the handmade often feels more precious. Artists like Francisco Goya used printmaking (etching and aquatint in his "Disasters of War") to document and critique the horrors of conflict and tyranny, showcasing its enduring power for social commentary even amidst industrialization.

Printmaking's Enduring Legacy: Master Printers and Contemporary Activism

Beyond the grand historical narratives, the profound journey of printmaking extends far beyond its technical mastery and artistic expression; it has always been a powerful tool for communication and social commentary, a means to democratize art, making it accessible to wider audiences than ever before. In the contemporary world, activist printmaking collectives continue this tradition, using screenprinting and other accessible methods to address social justice issues, proving that the medium's power to provoke thought and inspire change remains as potent as ever. Think of the powerful protest posters emerging from movements like the Black Arts Movement or environmental activism, where collective studios amplify voices that might otherwise be silenced. From protest posters to artists using printmaking to raise awareness, the medium continues to be a platform for voices that might otherwise be silenced.

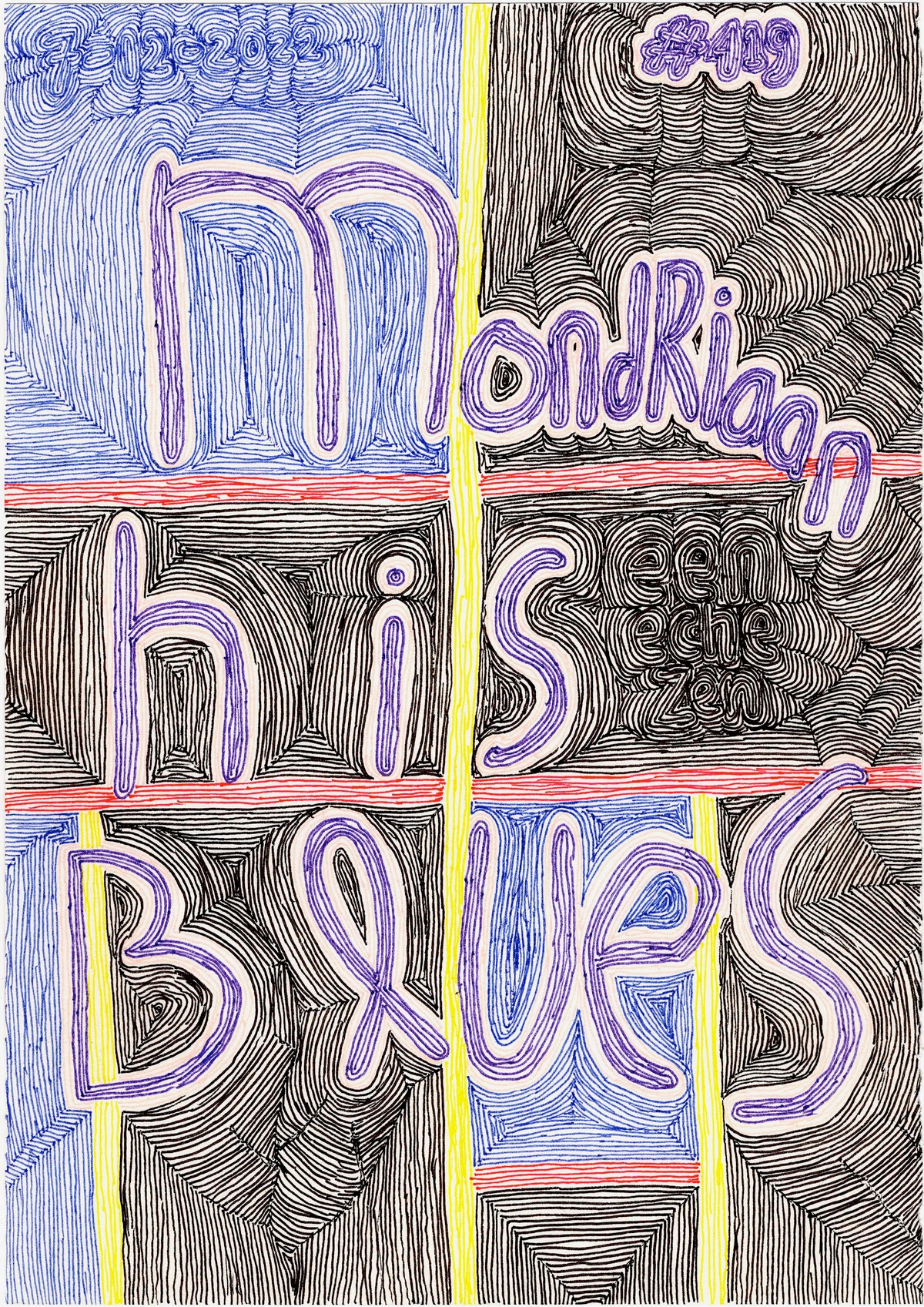

The role of master printers and specialized printmaking workshops cannot be overstated in this legacy. Throughout history and today, these skilled artisans work closely with artists, often translating an artist's vision into a print, pushing technical boundaries, and ensuring the highest quality in editions. This collaborative spirit is a testament to the community and dedication inherent in printmaking. For me, this rich history reminds us that art isn't just about beauty; it's about dialogue, about connection, and sometimes, about shaking things up. It’s a craft that combines the methodical precision of a scientist with the expressive freedom of a poet, creating an indelible mark on both paper and culture. My own artistic timeline shows how these historical currents continue to influence contemporary practice. What enduring messages do you think contemporary printmakers are leaving for future generations?

Printmaking as a Gateway to Other Art Forms

It might seem counterintuitive, but the discipline and creative problem-solving inherent in printmaking are not confined to the press. For me, the journey through its various techniques has profoundly influenced my approach to other artistic practices, especially painting. The meticulous planning required for a multi-plate intaglio or a multi-color screenprint sharpens my understanding of composition and color theory. For instance, the way I now consider negative space in my abstract compositions often comes from the inverse thinking forced by a linocut. The exploration of textures in collagraphy informs my material choices in mixed media, pushing me to integrate unexpected elements for a richer surface. Even the unexpected outcomes, those delightful 'happy accidents' from the press, teach me to embrace spontaneity and adapt in my painting process, much like letting a drip in a painting become an integral part of its flow. Printmaking, in essence, is a masterclass in visual communication that enriches the entire artistic toolkit, pushing me to find new connections and expressions across different mediums.

The Core Techniques: My Tangles with Tools and Ink

Now that we’ve traced printmaking's journey through history and society, let’s get our hands dirty and dive into the fascinating world of its core techniques. There are four main families of printmaking, and each feels like a different personality, a different challenge to my patience and artistic whims.

Relief Printing: The Art of Letting Go (of the Background)

Ever wondered how those bold, stamped images come to life? Relief printing is where many artists begin, and it’s gloriously straightforward in concept, if not always in execution. With relief printing, you carve away the parts of the matrix you don't want to print, leaving the image raised. Think of a rubber stamp. Ink (often water-based for beginners due to easy cleanup, or oil-based for richer colors and longer working times) is then rolled onto these raised areas, and when pressed, only what’s left behind transfers. It's the confident, direct shout of the printmaking family. Many relief prints, particularly historical woodcuts, were often of moderate to large scale, designed for impact or storytelling.

- Woodcut: The granddaddy of relief, with a history stretching back to ancient China and Europe. Often utilizing blocks of cherry, pear, or oak, working with wood's grain can be a battle, but the results are often wonderfully raw and expressive. It's chunky, it's earthy, it feels... ancient. I remember a particularly stubborn piece of oak that fought my gouges at every turn, refusing to yield the delicate curve I envisioned. The resulting jagged line wasn't what I planned, but it lent an unexpected, powerful energy to the piece, a reminder that sometimes the material has its own story to tell. The choice between side-grain wood (where the plank is cut parallel to the tree's trunk, offering a softer, more manageable surface for carving with the grain, ideal for expressive lines) and end-grain wood (cut perpendicular, much harder but allows for incredibly fine detail, often used for detailed illustrations) significantly impacts the final aesthetic. I often find myself admiring the bold, almost primal lines that emerge from a good woodcut. It reminds me of those days when I try to declutter my mind – keeping only the essential, carving away the noise. Pioneering artists like Edvard Munch (famous for "The Scream") used woodcut to great expressive effect, capturing raw emotion through its stark contrasts. What kind of essential story would you tell with the raw power of woodcut?

- Linocut: My personal comfort zone (if I had one in printmaking). Linoleum, a softer material, carves more smoothly and allows for finer detail. It’s less resistant than wood, making it a bit more forgiving for us impatient types. You can achieve incredible graphic quality with linocuts, from delicate patterns to strong, impactful imagery. Artists like M.C. Escher and Pablo Picasso explored linocut, pushing its boundaries for intricate and bold designs. I find it perfect for abstract forms, where the clean lines can really make a statement, often translating the sharp edges and dynamic compositions found in some of my abstract paintings into a new, graphic language. For beginners, easily accessible papers like Japanese Kozo or Mulberry offer beautiful results with their delicate yet strong fibers, allowing for a crisp transfer of ink. What kind of bold, graphic image would you want to bring to life with linocut?

Intaglio: Diving Deep into Detail and Discipline

Ready for something a little more intricate? Intaglio is relief's elegant, slightly more demanding cousin, where the image is incised into the surface of the plate (usually metal like copper or zinc). Ink is then forced into these recessed lines, the surface is meticulously wiped clean (a critical step to ensure only the incised lines print!), and under high pressure, the paper pulls the ink from the grooves. It’s all about the line, the depth, the texture. If relief is a confident shout, intaglio is a nuanced whisper. The deeper the incision, the more ink it holds, resulting in a darker, richer line. Conversely, a shallower mark will yield a softer, fainter line, offering incredible tonal control. Beyond lines, techniques like aquatint allow for broad areas of tone, creating painterly effects by controlling how acid bites the plate in a finely textured pattern. This "finely textured pattern" is typically achieved by dusting the plate with tiny particles of rosin, which are then heated to adhere. The acid then bites around these particles, creating a multitude of tiny pits that hold ink and produce a gradient-like wash when printed. This technique is often used for highly detailed works, from book illustrations to finely rendered portraits and landscapes, typically on a smaller or medium scale to allow for close inspection, and requires specialist presses and chemicals. This is also where techniques like chine-collé often come into play, where a thin, delicate paper is adhered to the larger printing paper during the printing process itself, adding subtle color or texture to specific areas, creating an added layer of intricate detail.

- Drypoint: This technique offers immediate, raw energy. You scratch directly into the plate with a sharp point, raising a burr (a tiny ridge of metal) along the lines. This burr holds extra ink, giving drypoint prints a wonderfully soft, velvety, slightly fuzzy line quality—a distinct tactile difference from the crisp lines of engraving or etching. It's less about chemical processes and more about direct drawing, and I appreciate its spontaneity and the intimate feel it creates. It’s like sketching with a needle, capturing a raw, immediate feeling, much like the spontaneous gestures in some of my more expressive abstract pieces. Can you almost feel the texture of those lines, a direct connection to the artist's hand?

- Engraving: Think of the old masters, like Albrecht Dürer, creating incredibly fine, precise lines with a specialized tool called a burin. It's slow, methodical, and requires immense skill and control. My hands usually start cramping just thinking about it, but the resulting crisp, clean lines have an unparalleled elegance. It’s a direct, physical process, demanding patience and a steady hand, almost like performing delicate surgery on metal. The precise control over line and tone makes it ideal for intricate details, often seen in scientific illustrations, currency, and high-fidelity art reproductions of old. Dürer’s precision always makes me marvel at the sheer dedication and unwavering hand required; it's a level of control I sometimes envy, especially when my own abstract gestures verge on beautiful chaos. What level of precision would you strive for if you had the patience of a saint (or Dürer)?

- Etching: My personal nemesis, because it involves acid and a level of control I sometimes question if I possess even in my daily life. You draw onto a wax-coated metal plate (a 'ground'), then dip it in acid. The acid 'bites' into the exposed lines, dissolving the metal and creating grooves. The longer it bites, the deeper the line, the darker it prints. Unlike the physical depth of a drypoint burr, etching's depth is achieved chemically, allowing for a wider range of subtle tonal variations. The magic of varying line weights this way is truly captivating, though the precise timing always makes me sweat a little. I once left a plate in for "just one more minute" that turned into ten, and let's just say the resulting abstract blob was certainly 'deep' but not quite 'art'. My studio assistant, a stoic type, simply raised an eyebrow and suggested, "Perhaps next time, a timer?" Master etchers like Rembrandt and Francisco Goya used this method to achieve incredible detail and emotive power, with Goya's "Disasters of War" series being a searing example of printmaking's societal impact. Can you imagine the patience required for those delicate, bitten lines, or the thrill of pulling a perfect proof after hours of acid-bath anxiety? This technique is typically employed for works of fine art, often on a smaller to medium scale, where intricate detail and tonal range are paramount.

Planography: The Surface Tension of Serendipity

Ever thought art could be a science experiment? This family is where things get a bit more scientific, playing with the simple principle that oil and water don't mix. The image is neither raised nor incised; it exists purely on the surface of the matrix. It's the intellectual, fluid dance of chemistry and art, a fascinating interplay where hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties dictate the image. Planographic prints can range from small, intimate works to large, mural-like pieces, depending on the artist's ambition and the available press.

- Lithography: The big one, invented in the late 18th century by Alois Senefelder. This technique was revolutionary because it allowed artists to draw and paint directly on the stone or plate with greasy materials (like special crayons or tusche—a liquid, greasy ink). The magic happens when the stone is then chemically treated, typically with a gum arabic solution (a natural resin that desensitizes non-image areas to grease), which desensitizes the non-image areas to grease, making them accept water. Meanwhile, the drawn, greasy areas repel water but accept oil-based ink. It’s an intellectual exercise as much as an artistic one, allowing for incredible tonal range and painterly effects. The sheer mystery of it, how the chemicals decide what stays and what goes, always fascinates me, almost like trying to understand human relationships. Its ability to capture nuanced tones made it a favorite for artists ranging from Honoré Daumier to Pablo Picasso. What complex tones or narratives would you entrust to the unique alchemy of lithography? Lithography is highly versatile in scale, from small book illustrations to large fine art prints, and is particularly valued for its painterly quality.

- Monoprint: The glorious, fleeting anomaly. While often grouped here, a monoprint is essentially a unique, one-off print. You create an image on a smooth surface (glass, metal, plastic) and transfer it once to paper. The beauty is that you can never quite replicate it. Each one is a singular moment, a fleeting thought captured, which I find incredibly profound, especially in a world obsessed with consistency. It's a testament to the idea that some beauty is meant to be experienced just once, like a perfect sunset. It's the spontaneous, singular whisper of a moment. For a quick dip into printmaking, try a monoprint! Simply paint or draw with water-based ink onto a smooth, non-absorbent surface, lay paper on top, and rub the back gently to transfer the image. Each attempt yields a unique, expressive piece, unburdened by the pressure of an edition. What momentary beauty would you try to capture, knowing it can never be truly replicated?

Screenprinting (Serigraphy): Bold Statements and Modern Magic

Want to make a statement? Screenprinting, also known as serigraphy, is probably the most versatile and commercially popular method. It uses a stencil to block ink (often acrylic-based or oil-based, depending on the desired effect and substrate) from passing through a mesh screen (traditionally silk, now often synthetic) onto the paper. Open areas of the stencil allow ink to pass through. Water-based inks are often favored for fabric and paper due to their easy cleanup with soap and water and vibrant, opaque results, while oil-based inks offer longer open times and richer finishes, often used for fine art editions. Layering colors is a common technique, and the precise alignment of multiple screens, known as registration, is crucial for creating cohesive, multi-colored images. Registration involves marking the paper and the screen so that each subsequent color layer is printed in the exact same position relative to the previous ones; achieving this precision can be a painstaking process but is essential for sharp, multi-color prints. This makes it perfect for vibrant, graphic designs. It’s the unapologetically bold, graphic voice of the printmaking family. Screenprints can range dramatically in size, from small graphic posters to massive art installations.

I love screenprinting for its boldness and its almost industrial aesthetic. It's the method famously employed by Pop Art icons like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jasper Johns, who elevated it to fine art, proving that reproducibility doesn't diminish artistic merit. You can delve deeper into his groundbreaking work in the ultimate guide to Andy Warhol and discover the ultimate guide to Pop Art. It’s the method that brings us everything from t-shirt designs to fine art editions. The clean lines, the flat colors, the ability to create impactful, repeatable imagery – there's something incredibly satisfying about it. Sometimes, I look at my own abstract paintings and wonder how their explosive colors would translate into the crisp, layered world of screenprinting, a different kind of challenge for a different kind of expression. This technique has also found its way into contemporary art studios globally, seen in major print biennials and galleries, showcasing its enduring relevance. What bold statement would you want to emblazon upon the world using the vibrant power of screenprinting?

Collagraphy: Building Texture, Layer by Layer

Just when you think you've seen all the ways to make an impression, there's collagraphy. This contemporary and endlessly experimental technique, often associated with relief or intaglio due to its tactile nature, involves building a matrix by collaging various materials onto a rigid base (cardboard, plastic, wood). Think fabric scraps, sand, string, textured papers, corrugated cardboard, bubble wrap, or even dried leaves – anything that creates a raised or lowered surface. Once sealed, ink (usually oil-based for its versatility and richness) is applied to both the raised surfaces (like relief) and the incised textures (like intaglio), offering incredible textural richness and unique visual effects. The varying textures of the collaged materials will hold and release ink differently, creating a fascinating range of tones and lines. I once used dried, crushed eggshells and twine on a plate, and the resulting print had an unexpected, almost fossilized quality that delighted me. It's a beautiful bridge between sculpture and print, allowing for a freedom of material exploration that speaks to my own love for diverse textures in art. It’s the adventurous, tactile explorer of the printmaking world. Collagraphs tend to be moderate to large in scale, emphasizing their textural qualities. What surprising textures would you combine to create a truly unique collagraph?

Printmaking Techniques at a Glance

Family | Key Principle | Typical Matrix Materials | Characteristic Look | Key Characteristic/Feel | Typical Scale/Application | Key Artists/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relief | Raised image prints | Wood, Linoleum, Rubber | Bold, graphic, raw lines; strong contrast | Direct, robust, often primal, expressive | Moderate to large, illustrative, impactful | Woodcut (Munch), Linocut (Picasso) |

| Intaglio | Incised image prints | Copper, Zinc, Steel | Fine, delicate lines; rich tonal depth | Precise, nuanced, textural, elegant, subtle | Small to medium, detailed fine art, book illustration | Etching (Rembrandt, Goya), Engraving (Dürer) |

| Planography | Image on surface, oil repels water | Limestone, Metal plates | Painterly, subtle tones; wide range of effects | Fluid, painterly, chemical finesse, spontaneous | Small to large, fine art, illustration, posters | Lithography (Daumier, Picasso), Monoprint |

| Stencil | Ink passes through open areas | Mesh screen (silk/synthetic) | Flat, vibrant colors; clean, crisp, bold edges | Graphic, versatile, impactful, modern | Varied, from small graphics to large installations | Screenprinting (Warhol, Lichtenstein) |

| Collagraphy | Built-up textural surface prints | Cardboard, Plastic, Found Materials | Varied, deep textures, rich surfaces; sculptural | Experimental, sculptural, tactile, surprising | Moderate to large, experimental fine art | Glen Alps (pionier) |

Beyond the Basics: Where Boundaries Blur and My Mind Wanders

As captivating as these traditional methods are, the beauty of printmaking is that artists are constantly pushing boundaries, never settling for the confines of a single technique. This leads to fascinating hybrid techniques, combining elements of different methods, a kind of artistic cross-pollination. This is where the true innovation often lies, and where I find myself most creatively intrigued, always seeking new ways to express the chaotic yet harmonious energy of my abstract vision. For instance, combining the incisive detail of an etching with the broad, flat areas of color from a screenprint creates a powerful contrast, much like placing a delicate whispered secret within a shouted declaration. Or consider a photo-etching plate, where a digitally manipulated image is transferred onto a light-sensitive plate and then etched, allowing for incredible photographic detail before being hand-pulled alongside a monotype layer, adding a unique, painterly gesture to each print.

This layering of precision, boldness, and spontaneity allows for an incredible depth of narrative and visual complexity, much like how different art movements (Cubism or Abstract Expressionism) borrowed and built upon each other. For my own abstract work, hybrid printmaking offers a playground for exploring how hard lines can interact with soft washes, how deliberate marks can coexist with accidental textures, constantly pushing the edges of what's possible and what feels right in a piece. The process itself becomes a reflection of life's complexities, a dance between intention and discovery.

Then there’s digital printmaking, which uses modern technology to create prints. While undeniably art, whether it truly "counts" as traditional printmaking is a philosophical debate that often centers on the artist's direct physical manipulation of a matrix and the manual process of transferring ink. However, what's clear is that digital tools often integrate seamlessly with traditional methods: think designing a stencil digitally for a screenprint, creating complex patterns for photo-etching plates (where a photosensitive emulsion is exposed to a digital image), or even using digital files to produce large-format giclée prints that are then hand-finished with traditional printmaking techniques like chine-collé (adhering thin paper to the print during the printing process) or hand-coloring. Giclée prints, known for their high quality and archival nature, have found a significant place in the contemporary art market for fine art reproduction and original digital editions, bridging the gap between digital creation and tangible art. Printmaking, in all its forms, continues to evolve, reflecting human ingenuity and our enduring desire to communicate through images. It's a testament to the timeless appeal of the matrix and the impression, a legacy that continues in every piece of art created today, including the vibrant works at my museum in 's-Hertogenbosch.

Preserving Your Impressions: Care and Conservation

For collectors and artists alike, understanding how to care for prints is as crucial as understanding their creation. Original prints, with their delicate inks and papers, require mindful handling to ensure their longevity and preserve their artistic and monetary value. Prints should always be stored or displayed in acid-free materials to prevent discoloration and deterioration over time. When framing, use archival mats and backing and consider UV-protective glass to shield the artwork from damaging light. Avoid direct sunlight and areas with high humidity or extreme temperature fluctuations, as these can cause warping, fading, or mold growth. It's a small effort, but one that ensures the magic of the impression endures for generations, much like the original Mesopotamian seals that have survived millennia because of the inherent stability of their clay matrix. Thinking about this also makes me reflect on the broader environmental impact of art-making; using eco-friendly inks and solvents, and ensuring proper waste disposal, is just as crucial for preserving our planet as it is for preserving our art.

Setting Up Your Own Printmaking Haven (Even a Small One)

After delving into all these techniques, perhaps a spark has been ignited? The thought of making your own prints can feel daunting, but you don't need a full-blown studio from day one. My own journey, and indeed the history of many artists, often started with humble setups – a kitchen table, a few basic tools, and a healthy dose of stubborn optimism. The joy of pulling that first print is incomparable; it's less about the grand setup and more about the curiosity and willingness to experiment. Always prioritize safety: ensure good ventilation, especially when working with oil-based inks and solvents, wear appropriate gloves and eye protection, keep a tidy workspace to avoid accidents, and research proper disposal methods for inks and solvents to protect yourself and the environment.

For relief printing, a fantastic starting point, essential tools include:

- Carving tools: Gouges and V-tools (look for beginner sets like Speedball or Flexcut).

- Brayer: A hard rubber brayer is good for beginners to roll ink evenly.

- Inking surface: A smooth, non-absorbent surface like glass or plexiglass.

- Paper: Any paper will work for practice, but specific printmaking papers like Japanese Kozo or Mulberry offer beautiful results with their delicate yet strong fibers.

- Inks:

- Water-based inks: Ideal for beginners due to easy cleanup with soap and water, faster drying times, and lower toxicity. They're great for vibrant, opaque colors.

- Oil-based inks: Offer richer colors, longer open times (stay wet longer on the block/plate), but require mineral spirits or a more eco-friendly alternative like vegetable oil for cleanup. They can create a beautiful luminosity and hold fine detail well. Always research eco-friendly solvents and proper disposal methods to minimize environmental impact.

- Pressure applicator: A baren (a hand tool for applying pressure) or even just a wooden spoon can substitute for a press.

A Simple Linocut Project for Beginners:

- Sketch: Draw a simple design (a favorite plant, an abstract shape) onto your linoleum block with a pencil.

- Carve: Using your carving tools, carefully remove the areas you don't want to print. Remember: what you carve away will be white (or paper color), and what you leave raised will be inked.

- Ink: Roll a small amount of ink evenly onto your inking surface, then roll your brayer over it until it's tacky and evenly coated. Transfer this ink onto the raised areas of your carved linoleum block.

- Print: Place your paper gently over the inked block. Use your baren or wooden spoon to apply firm, even pressure across the entire back of the paper. Work methodically.

- Reveal: Carefully peel back your paper to reveal your first print! Celebrate the magic, even if it's perfectly imperfect, because those happy accidents are often the best teachers.

The Last Impression: A Journey Continued

As we conclude this journey through the captivating world of printmaking, it's clear that it's far more than just ink on paper. It's a rich tapestry of history, technique, and deeply personal expression. From the bold cuts of wood to the delicate lines of a drypoint, and the surprising textures of a collagraph, each method offers a unique dialogue between artist and material, a continuous dance between control and happy accident. This winding journey through the craft has always paralleled my own artistic exploration, continually reminding me that the most profound expressions often emerge from a willingness to experiment and embrace the unexpected, much like how life itself often unfolds in beautiful, unplanned ways.

Whether you're an aspiring artist ready to carve your first linocut, a seasoned collector appreciating the nuances of an original print, or simply a curious mind drawn to the tangible magic of art, I hope this guide has deepened your appreciation for this captivating art form. For me, the journey into printmaking is an ongoing conversation—a challenge, a solace, and a constant source of wonder. The world of printmaking is vast and always evolving, much like art itself. So, keep exploring, keep questioning, and perhaps, take the first step to make your own mark. Considering the explosive colors and dynamic forms in my own abstract paintings, which printmaking technique do you think would best capture that energy, and what story would you tell with it? The presses are waiting.