Basic Drawing Techniques: Line, Shade, Observation & Bringing Ideas to Life - An Artist's Guide

Unlock the magic of drawing! Dive deep into essential basic techniques like observation, line, shading, perspective, and composition from an artist's personal perspective. Learn how these fundamentals bring depth, form, and your unique ideas – even abstract ones – to life on the page. Includes practical mini-exercises, tool tips, and advice on practice and overcoming frustration.

The Magic of Line and Shade: Basic Drawing Techniques, Observation, and Bringing Your Ideas to Life

Drawing. It feels like the most fundamental act of creation, doesn't it? Just you, a surface, and something to make a mark with. But oh, the places those simple marks can take you! For me, drawing has always been the bedrock, the quiet conversation I have with my ideas before they shout onto a canvas. It's where the initial spark takes shape, where I figure out the bones of a composition or the play of light. And at the heart of it? The humble line and the transformative power of shade.

I remember sitting at my grandmother's kitchen table as a kid, trying to draw the sugar bowl. I thought I knew what a sugar bowl looked like – round, with a lid. But my drawing just... stayed flat. It was frustrating! It looked nothing like the solid, curved object sitting right there. That little moment of disconnect, between what my brain thought it knew and what my eyes were actually seeing, was my first real encounter with the challenge of drawing. It's like the paper is stubbornly refusing to give up its two-dimensionality. But that's where understanding basic drawing techniques, especially how to use lines and shading, becomes your superpower. It's not about being 'good' at drawing right away; it's about learning the language, the visual alphabet that lets you speak your ideas onto the page. We're not diving into the wild world of color just yet – that's a whole other adventure, maybe one that leads to a colorful abstract painting – but focusing on the essential structure and form that lines and shades provide.

Why These Basics Are Your Artistic Foundation

Think of lines and shading as the alphabet and grammar of drawing. You can't write a compelling story without them. Even in the wildest abstract art or the most expressive modern art, the underlying principles of how marks interact and how tone creates form are still at play. Understanding how line defines space and how shade creates volume informs everything from realistic portraits to non-representational compositions. A confident line can suggest energy in an abstract piece, just as it defines the edge of a realistic form. The interplay of light and dark, created through shading, gives abstract shapes weight and depth, preventing them from feeling merely decorative. It's the first step in developing your unique artistic style, giving you the control to translate what you see (or imagine) onto the page with increasing accuracy and feeling. It's the foundation upon which all other visual art skills are built, whether you're painting, sculpting, or even working digitally.

And yes, even in abstract work, the tension between line and form, the push and pull of light and dark, is what gives it structure and emotional weight. For me, the bold lines and contrasting shades I learned in basic drawing are the hidden skeleton beneath the vibrant, often chaotic, surface of my abstract pieces. They provide the underlying rhythm and depth that makes the color sing. It's not just about rendering reality; it's about understanding the fundamental visual forces that make any image resonate.

But beyond just replicating the world, these basics are the tools you use to build new worlds from scratch. They are the language you use to give form to the swirling, often chaotic, ideas in your head. Learning to control a line or understand how light wraps around a form isn't just about drawing a perfect apple; it's about having the vocabulary to express a feeling, a concept, or a purely abstract visual thought. It's the bridge between the intangible spark of an idea and its tangible existence on paper.

The Power of Observation: Seeing Like an Artist

Before you even make a mark, the most crucial skill is observation. It sounds simple, right? Just look. But it's more than that. It's about really seeing the world around you – noticing the subtle curves, the way light falls, the relationships between objects. When I first started, I'd rush to draw what I thought something looked like, not what it actually looked like. My hand would move faster than my eye. Slowing down, observing edges, and how forms turn in space is game-changing. It's like learning a secret language the world is constantly speaking, and drawing is how you respond.

Training your eye is an active process. Try focusing on just one aspect at a time. Spend a drawing session looking only at the negative space – the shapes between objects – and drawing those. Or dedicate time to observing textures, trying to capture the rough bark of a tree or the smooth surface of glass just through variations in your marks. Another powerful exercise is contour drawing, which forces you to slow down and truly follow the edges with your eye as your hand moves. It feels awkward at first, like trying to write with your non-dominant hand, but it builds that crucial connection between seeing and doing. I remember spending an entire afternoon trying to draw just the outline of my own hand, focusing only on the bumps of the knuckles and the subtle curves of the fingers. It looked terrible, but I saw my hand differently afterward. Or try observing people – not just their outlines, but the subtle shifts in posture, the tension in a shoulder, the way weight rests on one leg. This kind of observation feeds directly into capturing movement and energy later on.

But observation isn't just for realism. For abstract work, you observe the qualities of things: the rhythm of waves, the energy of a crowded street, the tension between two contrasting shapes, the flow of paint. You observe how light creates mood, how textures evoke feeling. It's about seeing the underlying visual forces, the abstract language inherent in everything. Learning to observe these non-representational elements is just as vital as observing the shape of a hand. It's about seeing the world not just as objects, but as a dynamic interplay of visual forces.

Let's take it a step further. Look at everyday objects around you right now. Not just their outlines, but the way light pools on a curved surface, the subtle tension in a bent paperclip, the rhythm of folds in a piece of fabric, or the complex interplay of light and shadow on a crumpled piece of paper. These aren't just things to draw; they are lessons in form, light, and texture waiting to be discovered. Training yourself to see these details, even in the mundane, is key to bringing your drawings to life, whether you're aiming for realism or using these observations as inspiration for abstract forms.

Negative Space: Drawing the 'Nothing'

Often, what you don't draw is as important as what you do. Negative space is the area around and between the subjects of your drawing. Learning to see and draw these shapes can dramatically improve the accuracy of your positive forms. It tricks your brain into seeing the actual shapes rather than relying on preconceived notions of what an object 'should' look like. Try drawing a chair by focusing only on the shapes of the air between the legs and the backrest. It feels counter-intuitive, but it works wonders for improving proportion and placement.

Mini-Exercise: Find a simple object with interesting spaces within or around it, like a pair of scissors, a chair, or a plant. Draw only the shapes of the empty space around and through the object. Ignore the object itself. See how this changes your perception of its form.

Proportion and Measurement: Getting Things Right (or Intentionally Wrong)

Observation also involves understanding proportion – the size of one part of an object relative to another, and the size of objects relative to each other within a composition. Getting proportions right is fundamental to realistic drawing, but even in abstract work, a sense of visual balance and scale is crucial. You don't need a ruler! Artists often use techniques like sighting, holding their pencil at arm's length to measure angles or relative sizes, or using negative space comparisons. I used to get so frustrated when my initial sketches looked 'off' – a head too big for a body, or a table that seemed to tilt uphill. Learning basic sighting techniques felt like getting a secret decoder ring for visual reality. I remember trying to draw my cat once, and his head ended up being about a third of his body size. He looked like a bobblehead! It was a funny failure, but it taught me the hard way about checking proportions early on. Of course, once you understand the rules, you can intentionally break them for expressive effect, which is half the fun, especially in abstract or stylized drawing.

Drawing from Life vs. Photos

While photos are convenient references, drawing from life offers a richer observational experience. When you draw from life, you're interacting with a three-dimensional object in real space, under real light. You can walk around it, see how the light changes as you shift, and truly understand its form in the round. Photos flatten reality, sometimes distorting perspective or simplifying shadows. Drawing from life forces you to engage your eye and brain in a different, deeper way. I still try to draw from life whenever possible, even if it's just a quick sketch of my coffee cup – it keeps my observational muscles sharp in a way photos can't quite replicate. There's a certain energy and immediacy to capturing something live that a photo just can't replicate. It forces you to make quick decisions and focus on the essence.

The Humble Line: More Than Just an Outline

A line isn't just the edge of something. It's energy, direction, information. It can be bold and confident, or hesitant and searching. It can define form, suggest movement, or even convey emotion. The simple act of putting a line down is a commitment, a decision. What will it say? Lines are the initial thoughts, the raw energy of an idea taking its first breath on the page. Think of a line not just as a boundary, but as a path, a whisper, or a shout across the page.

Contour Lines: Defining the World

These are the lines that describe the outer and inner edges of a form. Drawing contour lines slowly, letting your eye follow the edges of an object, is a fantastic way to really see it. It's less about speed and more about observation. It's like tracing the boundary of a secret garden. Try drawing a simple object like a shoe or a crumpled piece of paper just by following its contours. Or try your own hand – I remember spending ages trying to get the knuckles right on my own hand, it was frustrating but taught me so much about subtle curves and overlaps. Mini-Exercise: Pick an object, any object, and draw it without lifting your pencil from the paper (blind contour drawing is even better!). Focus only on the edges. For a challenge, try blind contour drawing: place your paper and pencil in front of you, but look only at the object, not your paper, while you draw its contour. The results are often distorted and hilarious, but it's an incredibly effective way to train your eye to truly see the edges.

Gesture Lines: Capturing the Soul of Movement

Oh, gesture drawing! This is where the energy comes in. Quick, fluid lines that capture the action, the pose, the feeling of a subject, rather than the precise details. Think of a dancer or a running animal – gesture drawing is about the flow, the dynamism. It's messy, it's fast, and it's incredibly freeing. It's like trying to catch lightning in a bottle with your pencil. I love sketching people in cafes or parks; you only have a few seconds before they shift, forcing you to capture the essence, not the detail. My early gesture drawings looked like scribbles, and honestly, some still do, but they hold the life of the subject. The line of action is key here – the invisible line that captures the main thrust or energy of the pose. Embrace the mess! The goal isn't a finished drawing, but capturing that fleeting energy. Mini-Exercise: Find some photos of people or animals in motion. Set a timer for 30 seconds or a minute and do quick gesture sketches, focusing only on the main lines of action and the overall flow of the form.

Expressive Lines: Adding Your Voice

The thickness, thinness, smoothness, or shakiness of your line can say so much. A thick, dark line feels different from a faint, wispy one. Experiment with varying your line weight. It adds personality and drama. It's your handwriting on the page. Try drawing the same simple object (like an apple or a mug) three times: once with only thin, even lines; once with thick, bold lines; and once varying the line weight dramatically. Notice how the feeling of the object changes. What does a shaky line communicate? What about a confident, unbroken one? Mini-Exercise: Draw a simple shape (like a circle or square) and fill it with lines. Experiment with making the lines thick, thin, wavy, broken, or scribbled. See how the feeling changes. Now, try drawing the same simple object (like a tree or a rock) multiple times, but try to make one drawing feel 'sad' using only lines, another 'angry', and another 'peaceful'. Focus on how the quality of the line changes the emotional impact.

Bringing Form to Life: The Art of Shading

This is where the magic really happens. Shading transforms flat shapes into three-dimensional forms. Think of a circle (a 2D shape) versus a sphere (a 3D form). Shading is the tool that makes that transformation visible. It's how you show light hitting an object, creating highlights, mid-tones, and shadows. It's essentially playing with light and shadow on paper. It's like sculpting with graphite. I remember the first time I successfully shaded a simple sphere and it actually looked round, like I could pick it up off the page. It felt like pure magic, like I'd tricked the paper into having depth!

Before you jump into shading complex objects, a helpful step is to simplify them into basic geometric forms – spheres, cubes, cylinders, cones. Learn to shade these fundamental shapes first, understanding how light wraps around a sphere or how shadows fall on the planes of a cube. Once you can make these basic forms look three-dimensional, you can apply that knowledge to more complex subjects by seeing the underlying simple shapes within them.

Mini-Exercise: Pick a slightly complex object, like a crumpled piece of paper or a shoe. Before you draw the details, try sketching it first as a collection of simple spheres, cubes, and cylinders. See how these basic forms build the overall structure.

Seeing Value: Training Your Eye for Tone

Before you even pick up your shading tool, you need to learn to see the different tones, or values, in your subject. Value is simply the lightness or darkness of a color or shade. Squinting at your subject can help simplify the scene into broader areas of light, medium, and dark. Imagine converting the world into a black and white photograph – that's seeing in values. This is a crucial step before you start applying tone, as it helps you map out where your darkest darks and lightest lights will go. I often find myself squinting at things even when I'm not drawing, just to see the value patterns. It's a habit that sticks!

Understanding Light and Shadow

Before you shade, look at your subject. Where is the light coming from? Is it harsh and direct, or soft and diffused? The direction of your light source is absolutely critical – it dictates where your highlights will be, the shape and placement of your core shadows, and the direction and length of your cast shadows. Noticing these things is key. It's like being a detective for light. What parts are brightest (highlights)? This is where the light source hits directly. What parts are in shadow (core shadow)? This is the darkest part on the object itself, where light cannot reach. Where does the object cast a shadow onto the surface it's on (cast shadow)? This shadow follows the shape of the surface and the form of the object. Also, look for reflected light – subtle light bouncing back onto the shadow side of an object from the surface it's resting on – and occlusion shadows – the absolute darkest darks where two surfaces meet or an object touches the ground. These small details add so much realism. Here's a simple exercise: take a plain object like a ball or a cube and shine a single light source (like a desk lamp) on it from different angles. Observe how the highlights and shadows change. See how the cast shadow stretches and changes shape. It's fascinating how much information light gives us about form.

Another common pitfall for beginners (and something I struggled with!) is inconsistent lighting. If you're drawing from imagination or multiple references, make sure you decide on one light source direction and stick to it. Otherwise, your object will look confusing and flat, like it's being lit from everywhere and nowhere at once. Consistency is key to creating believable form.

Mini-Exercise: Place a simple object (like a mug or a box) on a table near a single light source (a lamp or window). Draw only the cast shadow it creates on the table and the wall behind it. Pay attention to the shape and how it changes if you move the light or the object.

Value Scales: Your Shading Compass

Before tackling complex forms, practice creating a value scale. This is a gradient showing the range of tones from pure white (no mark) to the darkest black your pencil can make. Learning to control the pressure and density of your marks to create smooth transitions across this scale is fundamental to realistic shading. I spent so much time just filling little boxes with gradients, trying to get them perfectly smooth. It felt tedious, but it built the control I needed. Sometimes it felt like a chore, but that control is everything when you want to make something look solid. Mini-Exercise: Draw a rectangle and divide it into 5-7 smaller boxes. Practice filling each box with a different, consistent tone, moving from lightest to darkest. Try doing this with just one pencil, focusing on varying your pressure.

Shading Techniques: Your Toolkit

There are several ways to apply tone. Each creates a different texture and effect. Mastering these techniques gives you a versatile toolkit for rendering form, texture, and atmosphere. I remember spending hours just practicing these, filling pages with squares and circles, trying to get smooth gradients or perfectly spaced lines. It felt tedious sometimes, but it built the muscle memory.

Technique | Description | Effect | My Experience/Tip | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hatching | Parallel lines drawn close together. | Creates texture and builds tone gradually. | Great for showing direction of form. My early attempts were always too messy! Keep your lines consistent and close. | Hair, fabric folds, wood grain, showing form direction |

| Cross-Hatching | Layers of hatching lines crossing each other. | Builds darker tones and adds more texture. | Essential for deep shadows. Getting the angles right takes practice. Don't be afraid to layer! | Deep shadows, rough textures, building tone quickly |

| Stippling | Creating tone using dots. | Can create subtle gradients and unique texture. | Requires patience! Good for fine detail or soft transitions if dots are small. My hand always cramped! | Skin texture, soft shadows, creating subtle gradients |

| Blending | Using a tool (finger, tortillon, paper stump) to smooth tone. | Creates smooth gradients and soft shadows. | Be careful not to over-blend and lose texture. My finger smudges were legendary. Use a tortillon for cleaner results. | Smooth surfaces (skin, metal), soft transitions, skies |

| Scumbling | Using random, circular scribbles. | Creates a rough, textured tone. | Fun and expressive! Good for organic textures like foliage or clouds. Embrace the chaos! | Foliage, clouds, rough surfaces, expressive marks |

Experiment with combining these! You don't have to stick to just one. Mini-Exercise: Draw a few simple shapes (circle, square, triangle) and practice shading each one using a different technique from the table. Try to make them look three-dimensional. Then, try shading a simple object (like a mug) using a combination of techniques – maybe hatching for the core shadow and blending for the mid-tones.

Edges and Texture

Beyond just smooth transitions, understanding edges is vital in shading. A hard edge clearly defines where one plane meets another or where an object ends. A soft edge suggests a rounded form or something receding into shadow or distance. Learning to control the sharpness of your edges with your shading tool (or eraser!) is key to making forms feel solid or soft. Similarly, shading isn't just about tone, but also about rendering texture. The way you apply your marks can suggest the roughness of stone, the smoothness of glass, or the softness of fabric. Experiment with varying pressure, direction, and technique to mimic different surfaces. Drawing a crumpled piece of paper is a fantastic exercise for practicing both edges and texture! I remember spending ages trying to get the crinkles and tears in a piece of paper to look right – it was frustrating but taught me so much about how light interacts with an uneven surface.

Don't forget your eraser isn't just for fixing mistakes! A kneaded eraser can be molded to lift tone gently, creating soft highlights or lightening areas without damaging the paper's surface. A sharp edge on a vinyl eraser can carve out crisp highlights or clean up edges. Learning to use your eraser as a drawing tool, adding light back into your shaded areas, is a game-changer for creating realistic form and texture. Mini-Exercise: Draw a dark, shaded rectangle. Use a kneaded eraser molded to a point to lift out small, bright highlights. Then, use a vinyl eraser with a sharp edge to carve out a crisp, straight line or shape within the shaded area. See how you can 'draw' with light.

Basic Composition: Arranging Your Visual Story

Beyond individual elements, how you arrange them on the page is crucial. Composition is the organization of elements in a work of art. It's how you guide the viewer's eye and create visual harmony or tension. Understanding basic principles helps make your drawings more dynamic and engaging. Learning composition felt like learning the choreography for my visual ideas – it's not just about what you draw, but how you present it. It changed the way I looked at everything, from a still life setup to the arrangement of objects on my desk.

Think about the Rule of Thirds: Imagine dividing your page into a 3x3 grid. Placing key elements along these lines or at their intersections often creates a more interesting and balanced composition than simply centering everything. Balance itself is key – is the visual weight evenly distributed, or is one side too heavy? You can achieve balance symmetrically or asymmetrically. Consider creating a Focal Point: What is the most important part of your drawing? Use contrast (light/dark, thick/thin lines), detail, or placement to draw the eye there. Other simple compositional tools include leading lines (lines that direct the viewer's eye through the image), framing (using elements within the scene to frame the main subject), and the visual appeal of odd numbers of objects. Mini-Exercise: Take a simple subject (like a single apple or a group of three simple shapes). Draw it three times in small thumbnail sketches: once centered, once using the rule of thirds to place the main subject, and once off-center but balanced with something else small in the frame. See how the feeling and visual interest changes with each arrangement.

Basic Perspective: Adding Depth to Your World

Once you understand line and shade, adding basic perspective unlocks a whole new level of realism and depth. Perspective is simply the technique artists use to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. It's closely related to composition, as it helps you place objects convincingly within that created space. Even understanding one-point or two-point perspective can dramatically improve your drawings of rooms, buildings, or objects in space. It's about understanding how parallel lines appear to converge at vanishing points on the horizon line, and how objects get smaller and less detailed as they recede into the distance. Think of looking down a straight road or train tracks – they seem to meet at a point far away. That's a vanishing point on the horizon line. Shading plays a role here too – shadows become softer and less defined further away. It felt like learning a bit of geometry, which wasn't my favorite subject in school, but seeing how it made my drawings pop was incredibly rewarding. I remember trying to draw my bedroom and the walls just wouldn't look right until I finally understood vanishing points. Suddenly, the room had depth! Mini-Exercise: Draw a simple cube or rectangle. Choose a horizon line and a vanishing point, and draw lines from the corners of your shape back to the vanishing point to create a sense of depth, making it look like a 3D box receding into space. Try adding a second vanishing point for a slightly more complex view.

Choosing Your Tools

For lines and shading, pencils are your best friend. A basic set with varying hardness (like 2H, HB, 2B, 4B, 6B) will give you a great range of tones. The harder pencils (H) make lighter, sharper lines, while softer pencils (B) make darker, richer marks and are better for shading. I personally love the range I get from a simple set of B pencils (2B, 4B, 6B, 8B) for most of my sketching and value studies. Charcoal is fantastic for rich, dark shadows and expressive lines, though it can be messy (a badge of honor, really). Vine charcoal is soft and easily blended or erased, great for quick sketches and tonal studies. Compressed charcoal is harder and produces darker, more intense blacks, perfect for strong lines and deep shadows. Ink pens offer crisp lines and require commitment – no erasing! Each tool has its own personality, and finding your favorites is part of the journey. Don't be afraid to experiment; sometimes the 'wrong' tool gives you the most interesting result.

Don't forget paper! The surface you draw on makes a huge difference. Smooth paper is great for fine lines and blending, while paper with more tooth (texture, like tiny bumps that grab the graphite) is excellent for techniques like hatching and stippling, as it grabs the graphite differently. Beyond just smooth or toothy, consider newsprint for quick, cheap studies (it's great for gesture drawing!), Bristol board for detailed, clean line work, or toned paper (like gray or tan) which allows you to work with both darks (pencil/charcoal) and lights (white charcoal/pencil) simultaneously, which is fantastic for practicing value and form. Experiment with different paper types to see how they interact with your chosen tools and techniques. Mini-Exercise: Take the same pencil and try drawing a simple shaded sphere on three different types of paper: smooth, medium tooth, and rough. Notice how the texture of the paper affects the shading and the overall look.

And erasers! They aren't just for fixing mistakes. A kneaded eraser is soft and pliable, great for lifting tone gently or creating highlights without damaging the paper. A gum eraser crumbles as you use it, which helps prevent smudging. A standard vinyl eraser is good for clean, precise erasing. Learning how to use your eraser as a drawing tool, not just a correction tool, is a game-changer for shading.

Oh, and a good pencil sharpener! It sounds obvious, but a dull pencil makes drawing frustrating. A sharp point is essential for crisp lines and fine details, while a slightly blunter point is better for broader strokes and shading large areas. Keep your pencils sharp, and your drawing life will be much happier. I'm slightly obsessive about having a perfectly sharp point before I start a detailed drawing.

Beyond traditional media, exploring digital drawing tools can also be incredibly rewarding. Tablets and styluses offer a vast range of brushes and effects, allowing you to experiment with line weight, texture, and blending in new ways. The principles of line, shade, composition, and perspective remain the same, but the tools offer different possibilities. It's just another way to make marks and bring ideas to life.

Practice Makes... Progress (and Sketchbooks Help!)

Nobody picks up a pencil and instantly draws like a master. It takes practice. Lots of it. Draw simple shapes and practice shading them to make them look three-dimensional. Draw everyday objects around your home – a mug, a shoe, a crumpled piece of paper, a piece of fruit. These simple subjects are fantastic for practicing observation, contour, and shading. Draw your hand (a classic challenge, trust me, even famous artists struggled with drawing hands!). Don't be afraid to make mistakes; they're just part of the learning process. The important thing is to keep drawing, keep observing, and keep experimenting. Even just 15-30 minutes a day can make a huge difference over time. It's about building muscle memory and training your eye. I have sketchbooks from years ago that are filled with truly terrible drawings, but flipping through them and seeing the small improvements is incredibly motivating. It's not about perfection; it's about consistent progress.

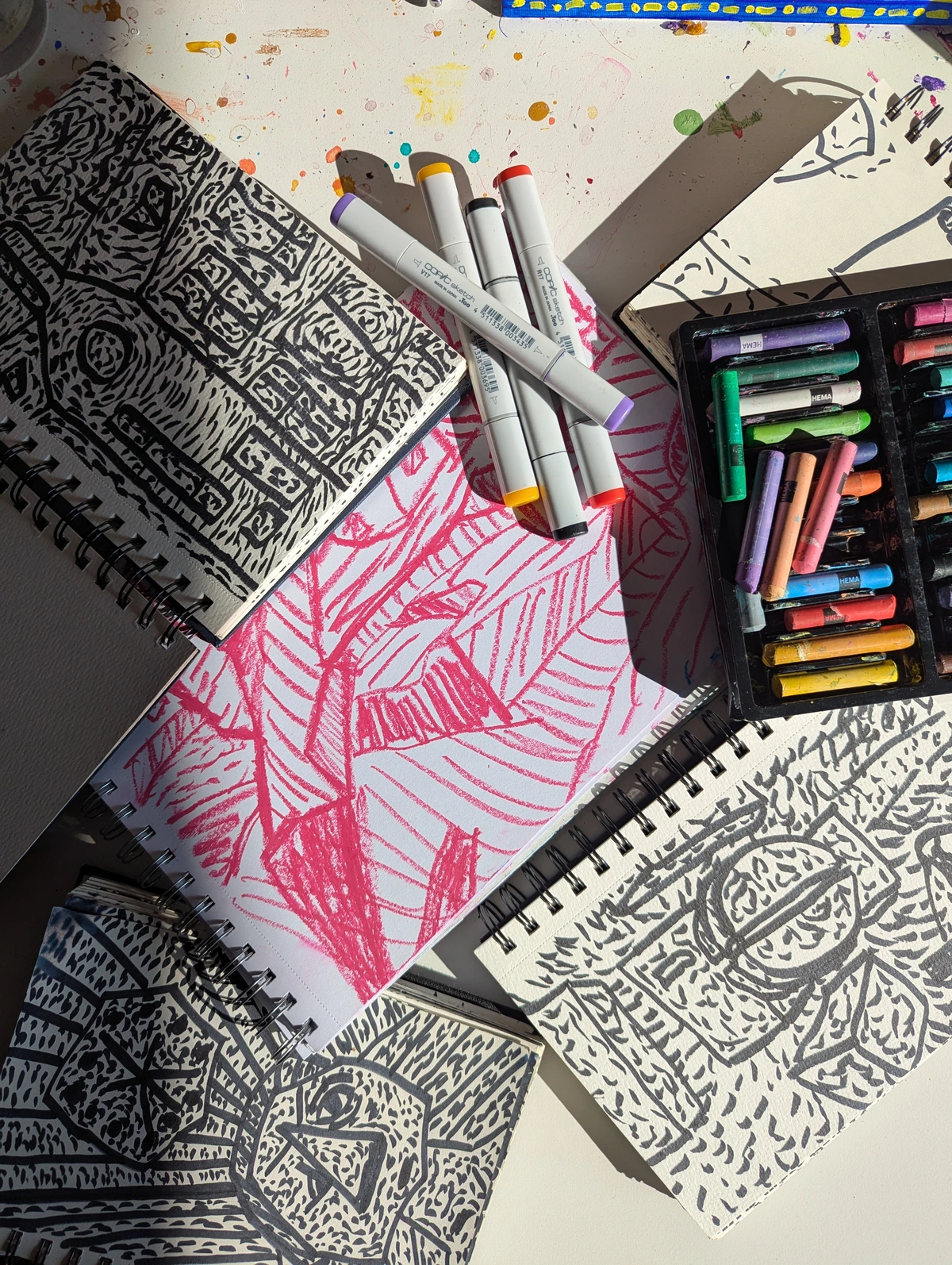

Consider keeping a sketchbook. It's your personal laboratory, a low-pressure space to experiment, make quick observations, practice techniques, and capture fleeting ideas. It doesn't have to be perfect; it just has to be used. Fill it with quick gesture sketches, studies of light and shadow, notes on composition, or just random doodles. It's also a fantastic place to brainstorm abstract ideas, experiment with mark-making without the pressure of a finished piece, or quickly visualize concepts buzzing in your head. Try drawing objects from memory, combining different everyday items in strange ways, or doing quick sketches based on emotions or sounds. It's a tangible record of your progress and a safe space to fail and learn. Don't let the fear of a blank page stop you – sometimes the first mark is the hardest, but once it's there, the possibilities open up.

Drawing from imagination is also a crucial skill that builds upon these basics. Once you understand how light falls on a form or how perspective works, you can apply that knowledge to visualize and draw things that don't exist in front of you. It's where observation meets invention, and it's incredibly rewarding. These foundational skills are just as applicable whether you're working with traditional pencils and paper or exploring digital art on a tablet.

Dealing with creative block? Sometimes the best way through is just to go back to basics. Pick up a pencil and draw a simple object, focusing purely on observation and technique. Or flip through your old sketchbooks for inspiration and a reminder of how far you've come. Sometimes just making any mark is enough to get the flow going again.

Connecting the Dots (and Lines and Shades)

These basic drawing skills are transferable. They inform how you see form and light, which is crucial whether you're painting, sculpting, or even doing digital art. Understanding how to create depth and volume with line and tone is a fundamental visual literacy. It's like learning to see the world in a new way. It's the backbone of everything I do, even when I'm working on a vibrant, abstract piece. The principles of composition, light, and form are always there, guiding the process.

And who knows? Maybe those initial sketches will evolve into something more. My own journey often starts with simple lines and tones, exploring an idea before it becomes a colorful abstract painting. It's all connected, really. From a quick gesture sketch in a cafe to a finished piece hanging in a gallery or even a museum, the line and the shade are the beginning. They are the foundation for bringing any idea, observed or imagined, to life. It's a journey of seeing, understanding, and translating the world – and your inner world – onto the page.

FAQ: Your Drawing Questions Answered

What are the most important basic drawing techniques?

Focus on understanding observation (both realistic forms and abstract qualities), different types of line (contour, gesture, expressive), shading (creating tone and form using value scales and techniques), basic perspective to create depth, and fundamental composition principles to arrange elements effectively. These work together to create volume, texture, and realism, and are essential for translating both observed reality and internal ideas onto the page. Don't forget the importance of consistent practice! It's the glue that holds it all together.

What's the best way to learn shading?

Practice creating value scales to control tone and pressure. Then, practice shading simple geometric shapes (spheres, cubes) under different light sources to understand how light and shadow fall (identifying highlights, core shadows, cast shadows, reflected light, and occlusion shadows). Pay close attention to the direction of the light source and ensure it's consistent. Experiment with different techniques (hatching, blending, stippling, scumbling) to see how they affect the result and texture. Learn to control edges (hard vs. soft) and render texture. Don't be afraid to use your eraser to lift tone and create highlights! Try shading a slightly more complex object like a crumpled piece of paper or a piece of fruit once you're comfortable with basic shapes.

What drawing tools do I need to start?

A few pencils of varying hardness (HB, 2B, 4B, 6B), a good eraser (consider a kneaded eraser for lifting tone), and drawing paper are a great start. I personally find a set of B pencils (2B, 4B, 6B, 8B) gives me a good range for most purposes. You'll also need a good pencil sharpener. You can add charcoal, ink, or blending tools like tortillons later if you like. Consider trying different paper types too – the tooth of the paper affects how marks look. Newsprint is great for quick studies, while Bristol board is good for detail. Exploring digital tools is another option. Don't feel like you need expensive supplies to start; a simple pencil and paper are enough.

How can I make my drawings look more realistic?

Pay close attention to observation – really look at your subject's forms, edges, and how light and shadow interact. Accurate observation and applying shading techniques to replicate those tones, along with understanding basic perspective and composition, will make a big difference in creating a sense of realism and volume. Drawing from life rather than just photos can also significantly improve your observational skills. Remember to simplify complex forms into basic shapes first and pay attention to proportion. It's all about seeing accurately and then translating that onto the page using your learned techniques.

Is drawing practice really necessary?

Absolutely! Like any skill, drawing improves with consistent practice. Even short, regular drawing sessions are more effective than infrequent long ones. Don't aim for perfection, aim for progress. Keeping a sketchbook for daily practice is highly recommended. It's your low-pressure space to experiment and learn. I still fill sketchbooks with quick studies and ideas! Think of it like training a muscle – consistency is key.

How long does it take to get good at drawing?

This is a tough one! There's no single answer. It depends entirely on how much you practice and how you practice. Some people see significant improvement in a few months of dedicated daily practice, while others take years. The key is consistency and focusing on understanding the fundamentals, not just trying to copy photos perfectly. Enjoy the journey! Don't get discouraged by slow progress; every mark is a step forward. It's a lifelong skill. And remember, 'good' is subjective; the goal is to be able to express your ideas.

What are common mistakes beginners make with line and shading?

Common mistakes include drawing too quickly without observing, using only outlines without shading to show form, not understanding how light hits an object (leading to flat shading), using inconsistent line weight or light sources, being afraid to make dark marks (lack of contrast), and not practicing value control. Don't be afraid of contrast! Also, beginners often neglect negative space and proportion, which are crucial for accurate placement and scale. And don't be afraid to make mistakes – they are part of learning. I still make plenty! Embrace the 'ugly' drawings; they are often the ones you learn the most from.

How do these techniques help me draw things from my imagination?

Understanding how light and shadow work, how forms exist in space (perspective), and how lines define shape gives you the visual vocabulary to construct images in your mind and translate them onto paper. You apply the same principles you learn from observing the real world to the world you create internally. Practice drawing from imagination alongside observation to build this skill. It's like building a visual library in your head – the more you observe and practice the basics, the richer that library becomes, allowing you to invent more convincingly. These skills are essential whether you're aiming for realism or creating abstract art.

How can I deal with frustration when learning to draw?

Frustration is a normal part of the process! Break down complex subjects into simpler shapes. Focus on one technique at a time. Don't compare your work to experienced artists; compare it to your own past work. Celebrate small improvements. Take breaks when needed. Remember that drawing is a skill that takes time and patience to develop. Your sketchbook is a great place to just play and experiment without pressure. Find a drawing buddy or online community for support and shared learning. It helps to remember that even the masters had to learn the basics! And honestly, sometimes just accepting that a drawing isn't working and starting a new one is the best approach. It's not failure, it's just one more practice session.

How important is the type of paper I use?

The type of paper, especially its tooth (texture, like tiny bumps that grab the graphite), significantly affects how your drawing tools interact with the surface. Smooth paper is good for fine lines and blending, while textured paper is better for techniques like hatching and stippling. Different paper types like newsprint, Bristol board, or toned paper offer unique properties for different purposes. Experimenting with different papers can open up new possibilities and textures in your work. It's worth trying a few different kinds to see what you prefer for different techniques. It's like finding the right canvas for a painting.

How do I choose what to draw?

Start simple! Draw everyday objects around you – a mug, a shoe, a piece of fruit. These are great for practicing observation, contour, and basic shading. Draw things that genuinely interest you, even if they seem simple. Use the mini-exercises throughout this article as prompts. Try drawing from observation one day and from imagination the next. Don't overthink it; just start making marks. Your sketchbook is the perfect place for low-pressure exploration. And remember, even a quick 5-minute sketch is better than no sketch at all! You could also try drawing based on abstract concepts, emotions, or even sounds – see where your lines and tones take you.

How do these basic drawing skills relate to abstract art?

Even in abstract art, the fundamental principles of line, shade, composition, and form are crucial. Abstract artists use line to create structure, movement, and energy. They use value and implied shading to create depth, tension, and visual weight, even without depicting recognizable objects. Understanding how light and shadow interact in the real world informs how an abstract artist might use contrast and tone to create dynamic compositions. Observation of the qualities of things – rhythm, tension, flow – directly translates into abstract mark-making and form creation. These basics provide the underlying visual language that makes abstract art resonate, giving it a 'hidden skeleton' of structure and depth, much like the foundation of a building allows for the expressive architecture above. My own abstract work relies heavily on the understanding of line and the interplay of light and dark that I developed through basic drawing practice. It's the silent language beneath the color and form.