Art Nouveau Artists: Visionaries, Style, and Enduring Legacy

Dive deep into Art Nouveau's iconic artists like Klimt, Gaudí, and Mucha. Explore their revolutionary designs, total art philosophy, unique craftsmanship, and lasting impact on architecture, graphic design, and decorative arts.

Art Nouveau Artists: The Visionaries Who Reimagined Beauty and Craft, and How They Still Inspire Us Today

Certain moments in art history possess a power that utterly captivates me, pulling me in with their unique blend of philosophy and visual splendor. If you've been following my musings here at Zenmuseum, you know Art Nouveau is one of those deep, abiding loves of mine. It wasn't merely a style; it was a philosophy – a vibrant departure from centuries of rigid artistic traditions, seeking to bring beauty into every facet of life. Imagine a world where art dared to dance with nature, where buildings bloomed like flowers, and furniture whispered secrets of the forest. It's where art truly started to break free from the stuffy confines of academic rules, embracing sensuality, organic forms, and the sheer joy of decoration. And honestly, this pursuit of organic freedom, this embrace of nature's wild, untamed beauty, resonates so deeply with my own contemporary work, where I seek to translate that same vibrant energy and expressive liberation through bold color and abstract forms.

But a movement, however grand, doesn't just spring up out of nowhere, does it? It's born from the minds and hands of visionary individuals who dared to dream differently. So, today, I want to take you on a personal journey through the lives and works of some of the absolute titans who sculpted, painted, and built the very essence of Art Nouveau, explaining not just who they were, but how their unique contributions shaped the movement and continue to inspire us. For me, diving into their work is like unlocking a secret language of form and color, a language I constantly try to translate into my own contemporary pieces.

credit, licence

What Even Is Art Nouveau, Anyway? Unpacking the Revolution

Before we dive into the fascinating personalities, let's just quickly refresh our memories. You might recall my definitive guide to the Art Nouveau movement, where I waxed poetic about its organic lines, natural forms, and a definitive break from copying old styles. But what really sets it apart? I think it boils down to a few core principles that artists across Europe championed in their quest to create a truly modern style – a conscious reaction against the impersonal industrial age and the rigid, often uninspired historicism (the borrowing of historical styles like Gothic or Renaissance) that preceded it. This era, often called the Belle Époque ("Beautiful Era"), was a time of relative peace and prosperity, technological advancement, and significant social change in Western Europe, and Art Nouveau artists sought to imbue this new world with beauty.

Key Principles Championed by Art Nouveau Artists

Art Nouveau was more than a decorative trend; it was a philosophy, a conscious effort to bring art and beauty into every aspect of life, reacting against the rigid, industrialized world. These were its beating heart, the concepts that defined the vision of its artists:

- Organic Lines and Natural Forms: At its core, Art Nouveau artists found their muse in the natural world. Think flowing curves, tendrils, and a rejection of straight lines and sharp angles. Artists looked to flora and fauna – climbing vines, delicate insect wings, the human body in motion – for inspiration. This is the famous "whiplash line" – a dynamic, asymmetrical curve that symbolizes growth, vitality, and boundless energy, much like a plant unfurling. It's like nature decided to get a little wild with a paintbrush, and we're all the better for it. When I'm working on an abstract piece, I often find myself consciously or unconsciously echoing this natural flow, trying to capture that same sense of dynamic, almost living, movement.

- Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art): The German term meaning "total work of art" was central to many Art Nouveau artists. They sought to unify all design into a harmonious whole, integrating architecture, furniture, painting, textiles, jewelry, and even everyday objects. Every detail mattered, creating immersive environments where structure and decoration were inseparable. For these artists, the art wasn't just on the canvas; it was the room, the building, the entire experience. It's an ambitious idea, isn't it? This holistic approach to art and design profoundly influences how I think about placing my own work within a space.

- Rejection of Historicism: Unlike earlier movements that borrowed heavily from classical, Gothic, or Renaissance styles – which Art Nouveau artists felt were stifling and outdated, offering only repetition – they wanted something entirely new. They aimed for a style for the modern age, free from the shackles of the past and its rigid academic rules, determined to forge a unique aesthetic identity. It was a bold declaration of artistic independence, a desire to look forward, not backward, that I find incredibly inspiring.

- Japonisme and Aestheticism: These pre-existing influences provided fertile ground for Art Nouveau artists. Japonisme (the profound influence of Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e prints by masters like Hokusai and Utamaro, on Western art) brought flat perspectives, bold outlines, simplified forms, and asymmetrical compositions – think of Hokusai's dynamic "Great Wave" and how its flowing lines and flattened forms resonate. You can clearly see this in the graphic works of the period. Aestheticism (the philosophy of "art for art's sake," championed by figures like Whistler and Oscar Wilde) prioritized beauty and sensory pleasure over moral or narrative content, giving artists permission to explore pure ornamentation and sensuousness for their own sake. Both liberated Art Nouveau artists to focus on visual impact and decorative elegance.

- Emphasis on Craftsmanship: As a powerful counterpoint to burgeoning mass production and industrialization, Art Nouveau artists celebrated skilled artisans and handcrafted quality. This wasn't just about painting; it was about exquisite metalwork, intricate glass, and finely carved wood, valuing the touch of the human hand in every creation. This dedication to material and process not only aimed to elevate the applied arts but also offered a human-centric response to the rise of the machine, a principle I deeply connect with in my own studio practice.

- A Synthesis of Art and Life: More broadly, Art Nouveau sought to dissolve the rigid boundaries between fine art and applied art. Its proponents believed that beauty should permeate everyday life, elevating utilitarian objects to works of art. From a teacup to a cityscape, the goal was to infuse every element of human experience with artistic intent. This principle of bringing art into life, making the ordinary extraordinary, is a guiding light for many artists today, myself included.

- Symbolism: While not always explicitly stated as a core principle, Art Nouveau often overlapped significantly with the Symbolist movement. Artists frequently imbued their organic forms and female figures with deeper, often mysterious, psychological, or mythological meanings, creating an art that evoked emotion and ideas rather than simply depicting reality. This focus on suggestion and allegory added a rich, evocative layer to the movement's visual splendor.

It’s also crucial to remember how it stands apart from what came next, especially that sleek, more geometric style known as Art Deco. While both were reactions to historical styles, Art Nouveau embraced organic complexity, while Art Deco championed streamlined, industrial elegance. If you're ever curious about the nuances, I highly recommend checking out Art Nouveau vs. Art Deco: Key Differences. But for now, let's focus on the individuals who gave Art Nouveau its beating heart during the vibrant period known as the Belle Époque.

The Visionaries Behind the Revolution: Iconic Art Nouveau Artists

This is where the magic truly unfolds for me. We're talking about folks who weren't just dabbling; they were diving headfirst into a new aesthetic, shaping the very fabric of our visual world. Here’s a rundown of some of the names you absolutely need to know, grouped by their primary contributions and geographical impact.

A. Architects of Wonder: From Brussels to Barcelona

Art Nouveau architects dared to break free from historical styles, creating buildings and interiors that felt alive, dynamic, and deeply connected to nature. They transformed cityscapes, making everyday utility into public art and championing the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal on a grand scale.

Victor Horta: The Architect of Whimsical Curves in Brussels

In Brussels, Victor Horta was pioneering Art Nouveau architecture with his graceful, flowing lines and total integration of design. His Hôtel Tassel (1893), often cited as one of the first true Art Nouveau buildings, is a marvel of exposed ironwork, glass, and intricate mosaics. Walking through his buildings, I feel like I'm inside a living organism, where every detail, from the staircase railings to the doorknobs, curves and flows with natural elegance. The central staircase in Hôtel Tassel, for instance, is a masterpiece of sinuous, plant-like ironwork, bathing in natural light from a skylight – a breathtaking example of structural elements becoming decorative art. Horta's innovative use of cast iron, not just as a structural element but as an expressive, decorative feature in works like the Hôtel van Eetvelde, perfectly embodied the Gesamtkunstwerk philosophy, where structure and decoration were inseparable. He understood the power of natural light and space, using it to emphasize organic forms and intricate details. It’s a complete experience, a truly immersive work of art, and it set the standard for what Art Nouveau architecture could be.

Hector Guimard: Paris Métro's Organic Entrances

If you've ever visited Paris, you've likely walked through a masterpiece by Hector Guimard without even realizing it. Guimard's iconic entrances to the Paris Métro system are the quintessential public face of French Art Nouveau. With their characteristic green, flowing ironwork reminiscent of plant stems and seeds, and often featuring ornate glass canopies, these structures transformed mundane subway entrances into sculptural gateways to the city. His most famous designs, like the instantly recognizable Mouton lampposts and railings, brought the organic elegance of Art Nouveau directly into the urban landscape, making everyday utility into public art. It's a testament to the idea that beauty shouldn't be confined to galleries but should enrich our daily lives, a core belief of many Art Nouveau artists that I wholeheartedly share.

Antoni Gaudí: Architecture That Dances with Nature in Barcelona

Now, if you want to talk about someone whose work truly feels like a living, breathing entity, then we absolutely must discuss Antoni Gaudí. This Catalan Art Nouveau architect took the organic principles of the movement and scaled them up to monumental proportions in Barcelona. His buildings aren't just structures; they're sculptural marvels inspired by nature – bones, trees, shells, even the human body. He was a master of trencadís, a mosaic technique using broken ceramic tiles, which imbued his surfaces with vibrant color and texture. What I find ingenious about using fragmented tiles for trencadís is how perfectly it allows for the creation of curved, undulating surfaces that mimic natural forms – a shimmering, textured skin for his organic architecture, often seen on the iconic chimneys of Casa Batlló or the serpentine benches of Parc Güell. It's an ingenious way to bring fragmented beauty into a cohesive whole, something I find fascinating and deeply inspiring for my own explorations of texture and pattern.

I mean, who else could design a church like the Sagrada Família, which looks like it's growing out of the earth, or the whimsical Casa Batlló with its dragon-like roof, skeletal balconies, and wave-like facade? And let's not forget the fantastical Parc Güell, where every bench, wall, and walkway is a celebration of organic form and vibrant mosaic. His disregard for straight lines and his embrace of rich color and innovative mosaic work are just astounding. It's like walking into a fantastical dream, an almost otherworldly experience that makes you question the boundaries of architecture. Gaudí reminds us that even the most functional things can be imbued with profound beauty and imagination. His work truly feels timeless, a testament to an unbridled creative spirit.

B. The Art of the Poster: Graphic Visionaries

Graphic arts were central to Art Nouveau's public face, making art accessible and pervasive through posters, magazines, and book illustrations. These Art Nouveau artists harnessed the power of new printing techniques, especially lithography, to spread the Art Nouveau aesthetic far and wide. They weren't just creating advertisements; they were creating art that permeated everyday life, transforming the urban landscape into a vibrant gallery.

Alphonse Mucha: The Master of the Divine Femme

If you've ever seen those lush, dreamy posters of beautiful women with flowing hair, surrounded by intricate floral patterns and mystical symbols, chances are you've encountered the work of Alphonse Mucha. This Czech artist, working primarily in Paris, became synonymous with the Art Nouveau aesthetic through his advertisements and decorative panels. He basically invented the iconic Art Nouveau woman – a figure of ethereal beauty and captivating grace, whose flowing hair and delicate features became instantly recognizable and deeply influential. His designs for legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt, such as the poster for Gismonda (1894), are breathtaking. Mucha didn't just sell a product; he created an entire universe of beauty and grace, filling every inch of the canvas with exquisite detail. His graphic style was also influenced by earlier illustrators like Eugène Grasset, who championed the decorative poster and whose flat areas of color and strong outlines laid groundwork for Mucha's distinctive look. It's this dedication to making every surface a canvas for beauty that I admire so much. His work truly defines Art Nouveau illustration and its widespread public appeal.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Bohemian Paris and Bold Graphics

While often associated with Post-Impressionism, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec also played a pivotal role in shaping the graphic look of Belle Époque Paris. His vibrant, often provocative posters for cabarets and entertainers, like the Moulin Rouge, shared Art Nouveau's embrace of bold outlines, flat areas of color, and dynamic compositions. His work, such as the famous Moulin Rouge: La Goulue poster (1891), captured the raw energy of Parisian nightlife with a fluidity and decorative flair that resonated with the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement, firmly establishing commercial art as a legitimate art form. He wasn't afraid to capture life as it was, in all its gritty glamour, making him a unique voice among Art Nouveau graphic artists. It's a reminder that beauty can be found even in the most unconventional subjects.

Aubrey Beardsley: The Dark Side of Decadence

Now, for a slightly different flavor. Aubrey Beardsley, the English illustrator, brought a strikingly different, often darker, edge to Art Nouveau. His monochromatic line drawings, with their intricate details and often provocative, decadent themes, are instantly recognizable. Beardsley, for example, created stunning yet unsettling illustrations for Oscar Wilde's play Salomé (1894), pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable. He used a highly stylized, almost woodcut-inspired ink work, creating sharp contrasts, elaborate patterns, and a certain unsettling elegance. His work often explored mythological and erotic subjects, proving that Art Nouveau wasn't just about pretty flowers; it also had a rebellious, sometimes unsettling, fascination with the exotic and the forbidden. This willingness to explore the less conventional aspects of beauty, even the 'darker' side of decorative art, is something I deeply respect in his approach, and it offers a powerful counterpoint to the more overtly decorative elements of other Art Nouveau illustrators.

C. Painting & Symbolism: The Viennese Secession

Art Nouveau in German-speaking countries was often known as Jugendstil ("Youth Style"), and in Austria, it found a unique expression through the Vienna Secession, a movement that pushed artistic boundaries with profound symbolism and opulent decoration. While sharing Art Nouveau's organic forms, the Secessionists often delved deeper into philosophical and psychological themes, leading to works of intense emotional and symbolic resonance. These Art Nouveau painters crafted a distinct, intellectually rich chapter for the movement.

Gustav Klimt: Gold, Symbolism, and the Viennese Secession

Ah, Gustav Klimt. Just the name conjures images of shimmering gold, enigmatic gazes, and profound symbolism. Klimt was a leading figure of the Vienna Secession, Austria's distinctive answer to Art Nouveau. While sharing Art Nouveau's organic forms and decorative elements, the Secessionists, under Klimt's influence, often delved deeper into Symbolism, exploring themes of love, death, and human sensuality with unparalleled opulence. You can learn more in The Vienna Secession: Art Nouveau's Radical Austrian Cousins.

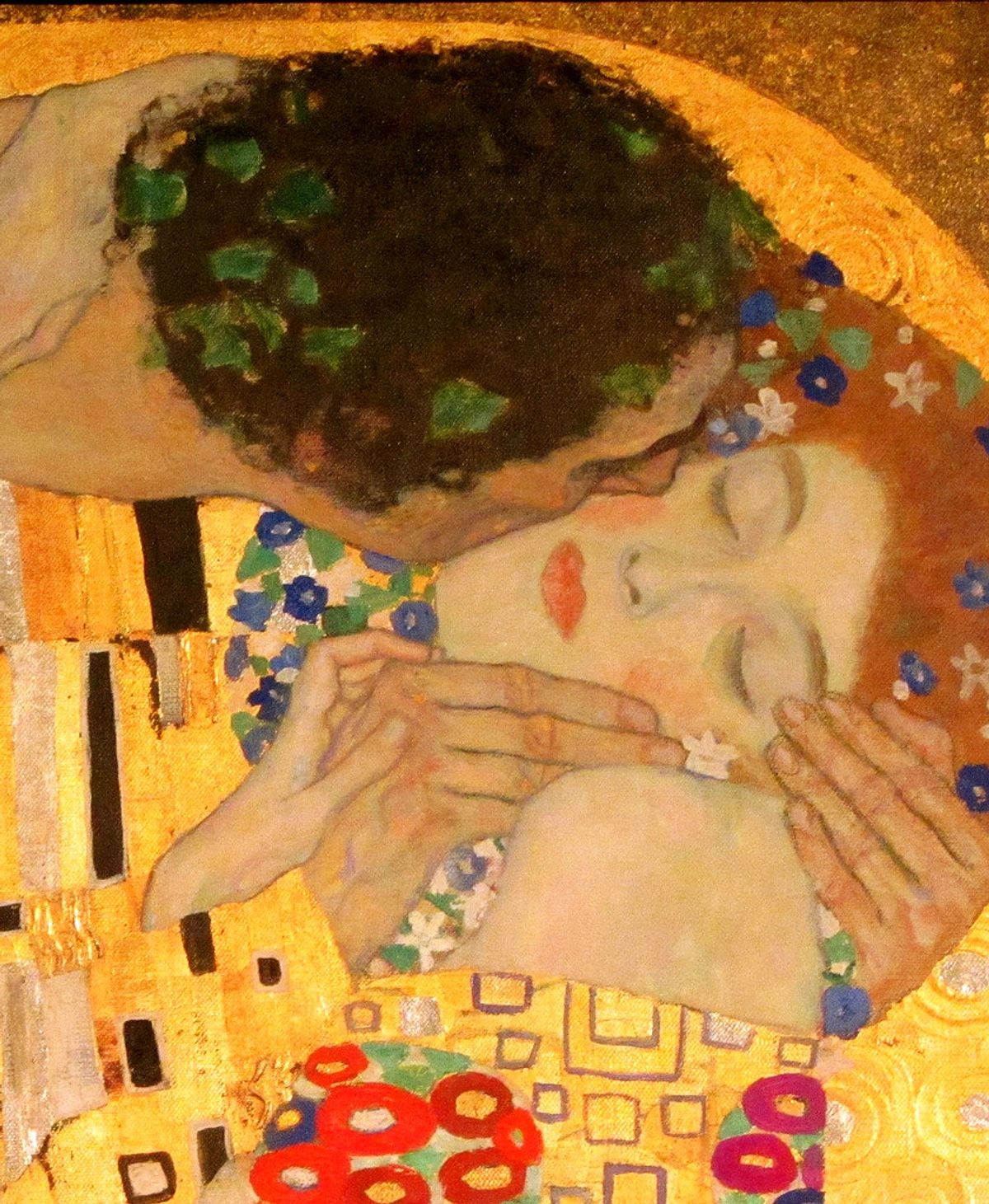

I remember seeing 'The Kiss' (1907-1908) for the first time – well, a really good reproduction, anyway – and being absolutely stunned by the sheer opulence and intimacy. The way the figures are intertwined, almost dissolving into a golden, mosaic-like embrace, with the man's head tilted towards the woman's cheek, creates an immediate, almost sacred intimacy. It’s a masterpiece that truly defines his "Golden Phase," where he incorporated shimmering gold leaf into his paintings, making them feel like ancient icons, yet utterly modern in their emotional depth. Another iconic work, Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1901), showcases his daring sensuality and the integration of painting into ornate, decorative frames, challenging conservative tastes. Klimt wasn't afraid to push boundaries, to challenge the conservative art establishment of his time. That takes guts, and it's something I deeply respect. If you've ever wondered about the layers of meaning in this iconic piece, check out What Is The Meaning of 'The Kiss' by Klimt?.

Speaking of the Vienna Secession, their building itself is an Art Nouveau icon! Designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, it was a place where artists, including Klimt, sought to create a total work of art, integrating architecture, painting, and decorative arts. The golden dome, the intricate details – it's a powerful statement of their artistic rebellion and commitment to the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal.

D. Decorative Arts & Crafts: Bringing Beauty to Life

Art Nouveau artists championed the decorative arts, blurring the lines between fine art and craftsmanship, and bringing exquisite, nature-inspired beauty into homes and everyday objects. This was where the Gesamtkunstwerk truly came to life, infusing everything from lamps to jewelry with artistic intent, and providing a direct response to the era's burgeoning industrialization, celebrating the skilled hand over the soulless machine. This emphasis also aligns with principles found in The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Return to Handcrafted Beauty.

Louis Comfort Tiffany: Bringing Nature's Glow Indoors

Across the Atlantic, Louis Comfort Tiffany was doing something equally revolutionary with light and color. While Gaudí built mountains, Tiffany created shimmering, jewel-toned landscapes for the interiors of homes. His stained-glass lamps and windows, with their intricate designs of dragonflies, wisteria, and peacocks, are pure Art Nouveau magic. His commitment to the decorative arts, and particularly his pioneering favrile glass (an iridescent art glass he patented), made him a fascinating figure if you're interested in Art Nouveau jewelry.

What I love about Tiffany's work, especially iconic pieces like the Dragonfly Lamp or his breathtaking "Magnolia" windows, is how he elevated a craft often considered secondary to painting or sculpture into an art form of incredible beauty and technical innovation. He developed new types of glass to achieve specific effects, mimicking the iridescence of beetle wings or the mottled texture of tree bark. It’s art that literally brightens a room, bringing the beauty of the natural world inside in the most exquisite way imaginable. This dedication to material, light, and bringing nature's luminescence indoors is something I find endlessly inspiring and strive to capture in my own abstract explorations of light and color.

Émile Gallé: The Poet of Glass and Wood from Nancy

Moving to Nancy, France, we encounter Émile Gallé, a true titan of French Art Nouveau and a leading figure of the Nancy School. Known primarily for his exquisite glasswork and furniture, Gallé was a botanist at heart, and his deep love for nature blossomed into intricate, multilayered glass pieces featuring etched floral motifs, insects, and landscapes. He pioneered techniques like cameo glass (where layers of different colored glass are cut away to create a relief design) and marqueterie de verre (a glass inlay technique), creating works like his famous Dragonfly Cup (c. 1900) that were both technically brilliant and deeply poetic. The intricate details of his glass, often depicting the ephemeral beauty of insects or the delicate forms of flowers, are simply mesmerizing. His furniture, too, often incorporated natural forms and intricate wood marquetry (like his "Ombellifère" desk), making him a prime example of an artist committed to the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal, where every object, however functional, became a work of art. The Nancy School, with artists like Gallé and Louis Majorelle, pushed the boundaries of functional art, creating a distinct, nature-infused aesthetic.

Art Nouveau in Everyday Objects: A Touch of Whimsy in the Home

Beyond grand architecture and major artworks, Art Nouveau truly shone in its application to everyday items. Artists and designers transformed mundane objects into pieces of functional art. Think of exquisitely designed silver cutlery with flowing handles that unfurled like fern fronds, ceramic vases blooming with stylized water lilies, intricate jewelry depicting dragonflies and femmes fatales, or elegant clocks encased in organic forms. Even furniture, textiles, bookbindings, and typography received the Art Nouveau touch, elevating the domestic sphere and printed page with beauty. This commitment to making art accessible and pervasive, integrating it into the fabric of daily life, was a hallmark of the movement and a profound influence on subsequent design philosophies.

Women of Art Nouveau: Crafting a Legacy

While male figures often dominate historical narratives, women played absolutely vital roles in shaping Art Nouveau, particularly in the decorative arts, jewelry design, and illustration. Their contributions were integral to the movement's Gesamtkunstwerk ideal, proving that artistry extends far beyond the canvas. Many of these talented individuals were at the forefront of the Art Nouveau design movement, pushing boundaries in both technique and aesthetics.

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, for instance, was an essential collaborator with her husband, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, in the Glasgow Style. Her ethereal gesso panels and intricate metalwork were central to their unified interior designs for places like the Willow Tea Rooms, adding profound symbolic depth and a quiet, dreamlike sensibility to his more rectilinear forms. Her highly stylized, elongated figures and intricate patterns became hallmarks of the Glasgow School, making it impossible to fully appreciate the Mackintoshes' vision without acknowledging her distinctive hand.

Another influential Scottish artist was Jessie M. King, a prolific illustrator and book designer known for her delicate line work, stylized figures, and strong Celtic influences. Her imaginative contributions, seen in works like her illustrations for "Buds and Blossoms" (1907), helped define the look of many Art Nouveau publications, making beautiful art accessible to a wider audience. Her work, characterized by dreamlike compositions and intricate details, often adorned books and decorative objects, embodying the movement's commitment to integrating art into everyday life. Beyond Scotland, Sarah Bernhardt, the legendary actress, wasn't just a muse but a savvy patron who actively commissioned works from artists like Mucha, directly influencing the popularization of the Art Nouveau aesthetic. And in ceramics, the Zsolnay Factory (Hungary) produced stunning iridescent glazes and organic forms, with many talented women designers contributing to their innovative output. These women, among many others in craft workshops and fashion houses across Europe, were not merely followers but innovators, pushing boundaries in materials and aesthetic expression and forming a crucial part of the Art Nouveau artist legacy.

E. The Glasgow Style: Refined Modernism from Scotland

From Glasgow, Scotland, emerged a distinct, more rectilinear, yet still undeniably Art Nouveau, aesthetic that would become highly influential. It offered a unique, often more subdued, interpretation of the movement's principles, a stark contrast to the exuberance of other European centers, but equally committed to integrated design.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Scottish Serenity Meets Flowing Lines

From Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh brought a more restrained, yet equally distinctive, version of Art Nouveau to the world. Often referred to as the "Glasgow Style," his work is characterized by a blend of strong vertical lines, subtle curves, and stylized floral motifs, particularly the iconic 'Glasgow rose.' I find his work incredibly calming, almost meditative. Think high-backed chairs, elegant interiors, and a masterful use of light and shadow, as seen in his designs for the Willow Tea Rooms (1903). Crucially, as I mentioned, Mackintosh worked extensively with his wife, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, whose symbolic and ethereal panel designs and metalwork were integral to their collaborative interiors and artistic vision, making the Glasgow Style a truly joint endeavor. He took the Art Nouveau principles of organic form and integrated design but gave them a unique, almost melancholic, northern European twist. His designs for the Glasgow School of Art were revolutionary, showcasing how modernism could be both functional and profoundly beautiful. He proves that Art Nouveau wasn't just about exuberant excess; it also had a quieter, more introspective side, perfectly illustrating the Gesamtkunstwerk principle in a different light. This subtle power, this quiet intensity that draws you in, is something I often try to evoke in my own abstract pieces, finding balance between bold expression and serene contemplation.

Materials and Techniques: The Craft Behind the Curves of Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau artists weren't just about new ideas; they were about new ways of making. The artists we've discussed leveraged specific materials and innovative techniques to achieve their signature looks. This commitment to craftsmanship was a direct response to the era's growing industrialization, celebrating the skilled hand over the soulless machine and pushing the boundaries of material expression. It stood in stark contrast to the burgeoning machine aesthetic that would later define parts of early Modernism.

- Cast Iron: Far from being a mere structural support, Art Nouveau artists like Horta (e.g., in the Hôtel Tassel staircase) and Guimard (e.g., in the Paris Métro entrances) transformed cast iron into an expressive, flowing, and decorative element. Its malleability when hot allowed them to mold it into organic forms, mimicking vines and plant stems, to create intricate railings, balustrades, and the iconic Métro entrances. The innovation here was elevating a heavy industrial material to delicate, sculptural art, blurring the line between engineering and ornamentation.

- Stained Glass: Louis Comfort Tiffany famously pioneered favrile glass, an iridescent, textured art glass that mimicked natural phenomena. Art Nouveau stained glass moved beyond traditional religious narratives, depicting intricate scenes of flora, fauna, and stylized figures, often used in lamps (like the iconic "Dragonfly Lamp"), windows, and decorative screens to create ambient, jewel-toned light. Tiffany’s innovation lay in creating glass itself as the artistic medium, developing new firing techniques and chemical compositions to achieve an unprecedented range of colors and textures, rather than merely coloring it.

- Cameo Glass: Émile Gallé was a master of this technique, involving layering different colored glass and then carving or etching away the top layers to reveal a relief design underneath. This created a sculptural effect with subtle color transitions, allowing for incredibly detailed natural motifs. His "Dragonfly Cup" is a prime example, where delicate insect wings appear to float within the glass. It required immense skill and precision, as each layer had to be carefully removed to achieve the desired depth and visual interplay, making each piece a unique work of art.

- Wood Marquetry: Both Gallé (e.g., his "Ombellifère" desk) and Mackintosh employed marquetry, an intricate inlay technique where pieces of veneer (often different woods, but also shell or ivory) are cut and fitted together to form decorative patterns or images on furniture. This celebrated fine woodworking and brought detailed, often botanical, artistry to functional objects. The challenge was in the meticulous cutting and fitting of disparate materials to create seamless, flowing designs.

- Trencadís: Gaudí's distinctive mosaic technique used broken ceramic tiles, glass, or marble shards. The irregular pieces allowed for dynamic, curved surfaces to be covered in vibrant, light-reflecting patterns, giving his Art Nouveau architecture (e.g., Parc Güell's benches or Casa Batlló's chimneys) a unique, almost living skin that shimmered under the Catalan sun. The genius was in embracing the imperfections of broken pieces to create organic, textured surfaces that couldn't be achieved with standard tiles.

- Lithography: For graphic Art Nouveau artists like Mucha and Toulouse-Lautrec, advances in lithography (a printing process using a flat stone or metal plate) allowed for the mass production of posters with rich colors and flowing lines, bringing Art Nouveau directly into the public sphere as a commercial art form. This democratic spread of art, making it accessible to everyone, was truly revolutionary for the time.

- Ceramics: Art Nouveau saw a significant revival in ceramics, with artists like Auguste Delaherche (France) and factories like Zsolnay (Hungary) producing stunning pieces. These works often featured organic forms, iridescent glazes, and hand-painted botanical or mythological motifs. Delaherche's stoneware vases, for example, showcased rich, often mottled glazes that mimicked natural textures, while Zsolnay's eosin glazes created a unique metallic sheen. Ceramics offered a versatile medium to bring Art Nouveau's decorative principles into homes, from large architectural tiles to delicate vases and tableware, demonstrating a fusion of utility and artistic expression.

- Jewelry: Art Nouveau jewelry was revolutionary, moving away from precious stones as the primary focus towards innovative designs and materials. Artists like René Lalique (e.g., his "Dragonfly-Woman" corset ornament) and Georges Fouquet (known for his sculptural pieces) created pieces that emphasized flowing lines, nature-inspired motifs (dragonflies, orchids, female forms), and the artistic use of enamel, horn, and semi-precious stones. It was about artistic vision and craftsmanship rather than material value, making each piece a miniature work of wearable art.

A Quick Look at the Masters: Who Did What?

To help you keep track of these incredible talents and their diverse contributions, here’s a handy summary of the key Art Nouveau artists:

Artist | Primary Medium(s) | Defining Characteristics | Regional Focus | Notable Works / Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoni Gaudí | Architecture | Organic forms, nature-inspired, vibrant mosaics, trencadís | Barcelona, Spain | Sagrada Família, Casa Batlló, Parc Güell (Barcelona's living Art Nouveau) |

| Victor Horta | Architecture, Interior Design | 'Whip-lash' curves, integrated design, exposed cast iron | Brussels, Belgium | Hôtel Tassel, Hôtel van Eetvelde (pioneering Art Nouveau architecture) |

| Hector Guimard | Architecture | Paris Métro entrances, cast iron, organic forms, public art | Paris, France | Métro entrances, Castel Béranger (made utility beautiful) |

| Alphonse Mucha | Lithography, Posters | Iconic 'Mucha Woman,' flowing hair, intricate floral motifs | Paris, France | "Gismonda" poster, elevating commercial art to fine art |

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec | Lithography, Posters | Bohemian life, bold outlines, dynamic compositions | Paris, France | "Moulin Rouge: La Goulue" (capturing Parisian nightlife) |

| Aubrey Beardsley | Illustration | Monochromatic line drawings, decadent, provocative themes | London, England | Illustrations for "Salomé" (intricate, sometimes unsettling line work) |

| Gustav Klimt | Painting | 'Golden Phase,' symbolism, sensuality, Vienna Secession | Vienna, Austria | "The Kiss," "Judith and the Head of Holofernes" (opulent, symbolic painting) |

| Louis Comfort Tiffany | Stained Glass, Lamps, Jewelry | Opalescent favrile glass, natural motifs | New York, USA | "Dragonfly Lamp," Tiffany windows (elevating stained glass as fine art) |

| Émile Gallé | Glass, Furniture | Cameo glass, marquetry, botanical themes, Nancy School | Nancy, France | "Dragonfly Cup," "Ombellifère" desk (poetic glass and wood artistry) |

| Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh | Decorative Arts, Metalwork | Ethereal gesso panels, symbolic motifs, Glasgow Style | Glasgow, Scotland | Collaborative interiors for Willow Tea Rooms, gesso panels (integral to Glasgow Style aesthetic) |

| Jessie M. King | Illustration, Book Design | Delicate line work, stylized figures, Celtic influences | Glasgow, Scotland | Illustrations for "Buds and Blossoms" (defined a distinct Scottish illustrative style) |

| Charles Rennie Mackintosh | Architecture, Design | 'Glasgow Rose,' elongated forms, subtle curves, serenity | Glasgow, Scotland | Willow Tea Rooms, Glasgow School of Art (master of the Glasgow Style) |

| René Lalique | Jewelry, Glass | Nature-inspired jewelry, art glass, innovative use of materials | Paris, France | "Dragonfly-Woman" corset ornament (pioneering Art Nouveau jewelry design) |

| Auguste Delaherche | Ceramics | Organic forms, innovative glazes, stoneware | France | Sculptural vases, art pottery (elevating ceramics to fine art) |

| Georges Fouquet | Jewelry | Sculptural, nature-inspired jewelry, innovative use of enamel | Paris, France | "Serpent" bracelet (master of Art Nouveau jewelry design) |

| Louis Majorelle | Furniture, Interior Design | Organic wood forms, marquetry, Nancy School | Nancy, France | "Water Lily" bed, complete interior schemes (key Nancy School furniture designer) |

The End of an Era: Why Art Nouveau Faded

It might seem counterintuitive for such a vibrant, forward-looking movement to have a relatively short lifespan (roughly 1890-1910). But I've found that movements, like trends, often contain the seeds of their own decline. For Art Nouveau, several factors contributed to its eventual, albeit temporary, fade from the forefront, largely stemming from the very characteristics that made it unique:

- Cost and Labor Intensity: The inherent craftsmanship and intricacy of Art Nouveau made it prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to produce, clashing with the growing demand for accessible, mass-produced goods. Imagine comparing the hundreds of hours of skilled labor required for a single, hand-carved, marquetry-decorated Art Nouveau cabinet versus a factory-made, simpler design. The former was a luxury only the wealthy could afford, making it unsustainable as the dominant style for an industrializing world.

- Changing Tastes and the Onset of Modernism: The exuberance and ornamentation of Art Nouveau began to feel excessive to a generation seeking greater functionality and clean lines. The horrors of World War I also led to a societal desire for austerity and a departure from the perceived decadence of the Belle Époque. Simplicity became the new sophistication, with movements like Functionalism, De Stijl, and Bauhaus explicitly rejecting Art Nouveau's decorative excess, pushing for a more rational, machine-age aesthetic.

- Rise of New Styles (Hello, Art Deco!): The geometric precision and streamlined forms of ultimate guide to art deco movement offered a stark contrast. Art Deco embraced industrial materials and machine aesthetics, providing a modern look that was easier to mass-produce and better suited to the post-war world's pragmatic mood. The shift was swift, almost a complete aesthetic pivot away from the organic curves of Art Nouveau.

- Lack of Cohesive Theoretical Framework: While Art Nouveau shared common principles, it lacked a single, overarching, explicitly declared theoretical framework or manifesto, such as those that would define later movements like Futurism or Surrealism. Its diverse regional manifestations meant it was often criticized for being purely decorative or lacking intellectual rigor by some critics who sought deeper philosophical underpinning in art. This sometimes made it harder to defend against the rising tide of new, more intellectually articulated avant-garde movements.

- Challenges for Artists: Many Art Nouveau artists, despite their innovative vision, often faced challenges in gaining widespread academic or institutional recognition. Their rejection of traditional art hierarchies meant they sometimes operated outside established circles, making financial stability and broad acceptance a struggle. While challenging, this independent spirit also allowed for immense creative freedom.

Despite its decline as the dominant style, its principles laid significant groundwork for later movements like early Modernism and its push for originality and integrated design. Its influence, I think, never truly disappeared; it just went underground, waiting for new artists to rediscover its magic.

Beyond the Canvas: The Enduring Legacy of Art Nouveau Artists

It might seem like a long time ago, this late 19th, early 20th-century movement. But I genuinely believe the legacy of these Art Nouveau artists is still profoundly relevant today. They taught us the value of originality over imitation, the beauty of natural forms over rigid geometry, and the importance of art permeating every aspect of life. Their rebellious spirit, their desire to create something entirely new, and their emphasis on fine craftsmanship as a counterpoint to mass production, is something I strive for in my own work – a continuous exploration of color and form, pushing past what's expected.

Art Nouveau's pervasive nature, extending into furniture, jewelry, textiles, ceramics, and even typography, truly embodies the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal. Its principles laid significant groundwork for later movements like early Modernism and its push for originality and integrated design. They remind us that art isn't just for galleries; it's in the architecture around us, the lamp illuminating our homes, the book covers we read, and even in modern graphic design elements. In fact, you can still see Art Nouveau's influence in modern design in things like organic furniture shapes, fluid typography, intricate patterns in fashion, or even the whimsical elements of digital interfaces. This holistic approach to art and design, the idea that every detail matters, is a powerful concept that resonates deeply with contemporary artists and designers, myself included.

Where to See Art Nouveau Today

If you're ever lucky enough to travel, I highly recommend seeking out Art Nouveau masterpieces by these visionary artists. Paris has the Métro entrances by Hector Guimard, while Brussels boasts Horta's incredible houses like the Hôtel Tassel. Barcelona is a living museum of Gaudí's genius (don't miss Parc Güell and Casa Batlló!). And of course, Vienna is a must for Klimt and the Secession building. For a deep dive into glass and furniture, Nancy, France, is an essential stop to appreciate the work of Émile Gallé and the Nancy School. And for an architectural feast, Riga, Latvia, has one of the highest concentrations of stunning Art Nouveau architecture in the world, with its elaborate facades a testament to the movement's global reach. Even Scandinavia (with artists like Otto Eckmann) and parts of the United States (like Tiffany's New York work, and buildings in Chicago or New Orleans) offer fascinating glimpses.

These places are living testaments to a time when artists dreamed of transforming the everyday into something extraordinary. If you're interested in art history, visiting these sites is like stepping directly into a vibrant, creative past. Or if you want to experience art that continues to push boundaries, you can always explore my latest creations here – it's a different era, but the spirit of breaking free is very much alive! Perhaps a visit to the Den Bosch Museum might offer some answers to what contemporary art is doing, or looking at art through the timeline could provide some perspective on how art evolves. Who knows what inspiration you'll find there, or even here, on these pages.

FAQ: Your Burning Questions About Art Nouveau Artists

Q: Who is considered the most famous Art Nouveau artist?

A: That's a tough one, as fame is subjective and varies by medium! However, Alphonse Mucha is arguably the most widely recognized for defining the illustrative style of Art Nouveau, especially through his iconic posters. Gustav Klimt is incredibly famous for his opulent paintings like 'The Kiss', and Antoni Gaudí for his unique, organic architecture in Barcelona. Globally recognized titans also include Louis Comfort Tiffany (stained glass and jewelry), Émile Gallé (glasswork), Victor Horta (architecture), and Hector Guimard (Paris Métro entrances).

Q: What are the key characteristics of Art Nouveau art?

A: Art Nouveau is primarily characterized by its rejection of historicism in favor of a completely new style inspired by nature. This translates to flowing, organic lines (the "whiplash line"), botanical motifs, and an emphasis on the integration of all art forms (Gesamtkunstwerk). It also draws from Japonisme (flat perspectives, bold outlines) and Aestheticism ("art for art's sake"), celebrating beauty, sensuality, and fine craftsmanship as a counterpoint to industrialization. A core principle was also the synthesis of art and life, bringing beauty to everyday objects. Additionally, many works carried profound Symbolism.

Q: What distinguished Art Nouveau artists from previous movements?

A: Art Nouveau artists explicitly rejected the historicism and eclecticism of previous movements, like Neoclassicism or the Gothic Revival, seeking to create a completely new style for the modern age. They drew inspiration directly from nature (curvilinear forms, botanical motifs, the 'whiplash line') rather than historical precedents. They also emphasized the integration of all arts (Gesamtkunstwerk – painting, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts, fashion, typography) into a unified aesthetic, and a profound respect for fine craftsmanship as a counterpoint to mass production, often elevating traditionally "minor" arts like ceramics or jewelry.

Q: What is the 'whiplash line' in Art Nouveau?

A: The "whiplash line" is one of the most distinctive and recognizable features of Art Nouveau. It refers to a dynamic, asymmetrical, and often sinuous line that sweeps and curves, reminiscent of a cracking whip, a tendril of a plant, or a flowing strand of hair. This organic, energetic curve symbolizes growth, vitality, and natural movement, appearing in everything from architectural details and furniture to graphic design and jewelry. It was a deliberate rejection of the straight lines and rigid geometries common in earlier, more classical styles.

Q: What is Gesamtkunstwerk and why was it important in Art Nouveau?

A: Gesamtkunstwerk (German for "total work of art") was a central and ambitious concept for Art Nouveau artists. It signified the desire to create a unified, harmonious artistic environment where all elements – architecture, interior design, furniture, painting, sculpture, textiles, and decorative objects – were meticulously designed and integrated to form a single, cohesive work of art. This holistic approach aimed to dissolve the traditional hierarchy between fine arts and applied arts, elevating every detail to an artistic statement and creating truly immersive, beautiful experiences.

Q: Did Art Nouveau artists work in specific cities? How did it vary?

A: Absolutely! Art Nouveau was a truly international movement, but it manifested differently in various cities and regions, often developing unique local 'flavors.' For instance:

- Paris was home to Mucha, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Guimard, known for graphic arts and elegant architectural details.

- Vienna to Klimt and the Secessionists, characterized by deeper Symbolism and opulent ornamentation, often with more rectilinear elements.

- Brussels to Horta, pioneering integrated architecture with exposed cast iron and organic curves.

- Barcelona to Gaudí, known for monumental, nature-inspired architecture with vibrant mosaics (trencadís).

- Nancy, France, to Gallé and the Nancy School, focusing on exquisite glass and wood marquetry with botanical themes.

- Glasgow to Mackintosh, featuring a more restrained, rectilinear, yet still flowing aesthetic, often called the Glasgow Style.

- Riga, Latvia, became a significant center for Art Nouveau architecture, boasting one of the highest concentrations of buildings in this style globally, with elaborate facades.

Q: Were there any female Art Nouveau artists?

A: Yes, absolutely! While many of the most prominently featured architects and painters of the era were men, women certainly played significant, often foundational roles, particularly in the decorative arts, jewelry design, and illustration. Artists like Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (Charles Rennie Mackintosh's wife and essential collaborator in the Glasgow Style, known for her intricate gesso panels and metalwork) and Jessie M. King (a highly influential Scottish illustrator and book designer) were incredibly talented and influential within the movement. Beyond individual artists, women were also crucial to the craft workshops, fashion houses, and ceramic factories (like Zsolnay) that embodied Art Nouveau's aesthetic, with their contributions increasingly recognized today.

Q: What is the symbolism of common Art Nouveau motifs like dragonflies or lilies?

A: Art Nouveau artists frequently drew from nature, imbuing their motifs with symbolic meaning:

- Dragonflies: Often symbolize change, transformation, and adaptability, as they metamorphose from aquatic larvae to winged insects. They also represent the ephemeral beauty of nature.

- Lilies (especially water lilies): Frequently associated with purity, beauty, and often, death or transition due to their appearance on water surfaces and short bloom cycles. The water lily specifically could also symbolize the mystery of the unconscious or the boundary between worlds.

- Peacocks: Symbolized immortality, vanity, and beauty, often used for their iridescent feathers and stately presence.

- Long-haired women: Frequently depicted as ethereal, mystical beings, embodying sensuality, nature, and the femme fatale archetype, often representing ideal beauty or spiritual insight.

- Wisteria: Symbolized longevity, immortality, and grace, known for its long, cascading blooms.

These motifs were not merely decorative; they were chosen to evoke deeper emotional, psychological, or spiritual resonances, aligning with the broader Symbolist tendencies of the era.

Q: How did Art Nouveau influence later art movements?

A: Art Nouveau, with its emphasis on decorative arts, functional beauty, and a rejection of academic tradition, laid significant groundwork for later movements. It directly influenced Art Nouveau vs. Art Deco: Key Differences (though Art Deco embraced more geometric forms and industrial materials) and was a crucial precursor to Modernism's push for originality and integrated design. Its celebration of craftsmanship, use of organic forms, and holistic approach to art continue to influence contemporary design, fashion, and architecture. You can learn more about its lasting impact in Art Nouveau's influence in modern design.

Q: What is the difference between Art Nouveau and Jugendstil/Secession?

A: Art Nouveau is the overarching international movement, but it took on different names and slightly different characteristics in various regions. Jugendstil ("Youth Style") was its name in German-speaking countries, particularly Germany. In Austria, the movement was known as the Vienna Secession. While sharing Art Nouveau's core principles of organic forms and decorative beauty, the Secessionists, led by Gustav Klimt, often emphasized Symbolism more deeply, exploring psychological and philosophical themes with opulent ornamentation, sometimes with more rectilinear forms than the flowing 'whiplash' lines typically associated with French or Belgian Art Nouveau.

My Final Thoughts

Looking back at these incredible Art Nouveau artists, I'm always struck by their courage. They stepped away from what was comfortable and expected to forge something utterly fresh and vibrant. It’s a powerful lesson for any artist, really – the importance of finding your own voice, even if it means bending the rules, or, in their case, the lines. Their legacy isn't just in the beautiful objects and buildings they left behind, but in the enduring spirit of innovation, the belief in quality craftsmanship, and the idea that beauty should be woven into the fabric of everyday life. And that, my friends, is a philosophy I can absolutely get behind. Every brushstroke I make, every color I choose, feels like a conversation with these masters, continuing their quest for a world where art isn't just observed, but lived.