Leonardo's Last Supper: Ultimate Guide to Da Vinci's Masterpiece & Its Legacy

Explore Leonardo da Vinci's 'The Last Supper'. Uncover its dramatic narrative, groundbreaking technique, profound symbolism, turbulent history, and enduring legacy from an artist's perspective.

Leonardo's Last Supper: The Ultimate Guide to Da Vinci's Masterpiece and its Enduring Legacy

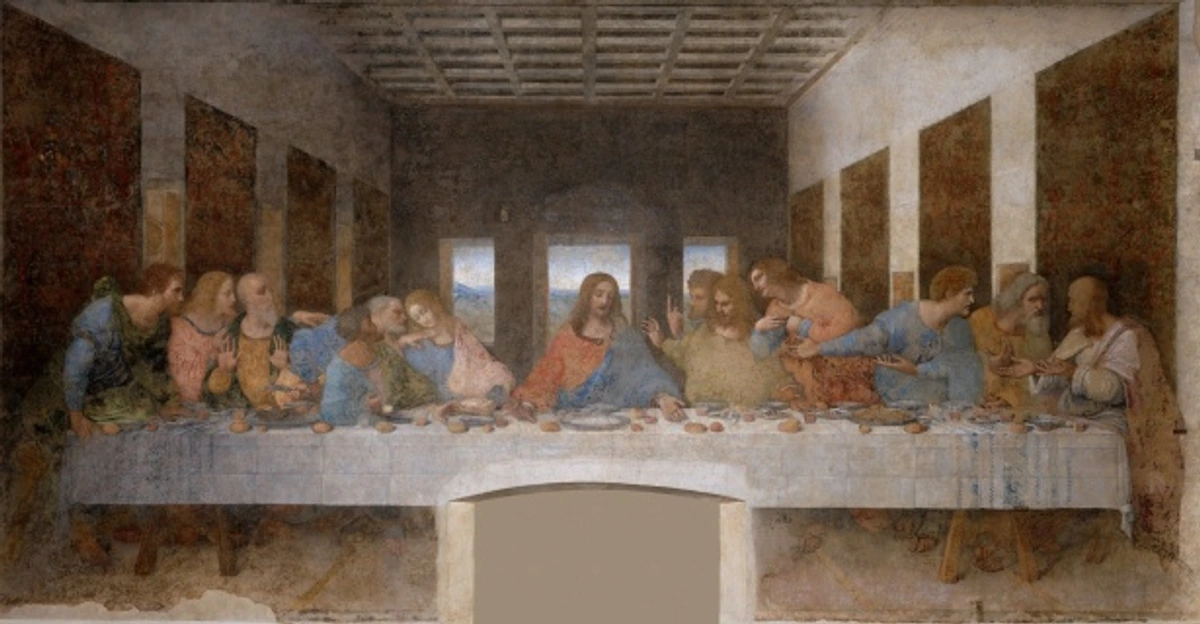

Imagine standing before a painting, and it's not just colors on a wall, but a captured explosion of human emotion, a pivotal moment frozen in time that feels profoundly real. For me, Leonardo da Vinci's 'The Last Supper' is absolutely one of those artworks. I remember seeing a high-quality reproduction for the first time – the original, as you know, isn't exactly a casual day trip – and being utterly mesmerized. It wasn't merely a depiction of a historical event; it was a profound narrative packed with layers of symbolism, raw human drama, betrayal, and divine foresight. And that, I believe, is where its true, resonant meaning begins to unfurl. This masterpiece challenges us to look beyond the canvas, to see into the very soul of humanity itself, grappling with loyalty, doubt, and an uncertain future. It’s also colossal, measuring approximately 4.6 meters by 8.8 meters (15 feet by 29 feet), a scale that demands awe and took Leonardo nearly three years to complete.

Ready to peel back those layers together and explore why this particular interpretation has captivated generations? In this ultimate guide, we'll unravel the layers of meaning, artistic genius, and enduring impact of Leonardo da Vinci's 'The Last Supper'. We'll dive deep into its biblical narrative, Leonardo's groundbreaking (and problematic) technique, its profound symbolism, the individual reactions of its key players, its tumultuous conservation history, and its enduring impact on art and humanity. Let's dive in.

The Foundational Story: A Meal That Changed History

Before we dive into Leonardo's brilliant interpretation, it's truly crucial to understand the foundational story of Jesus's last meal. The Last Supper, as recorded in the Gospels, wasn't just any dinner party; it was a Passover Seder, a traditional Jewish feast commemorating the liberation from slavery in Egypt. Imagine the weight of history, culture, and religious significance already present in that room. For centuries, Jewish families had gathered for this meal, recounting the Exodus story, using symbolic foods to remember their heritage and God's covenant – a covenant based on law and ritual. The very air would have been thick with expectation, tradition, and memory, an act of profound remembrance for a people's deliverance.

During a traditional Seder, specific symbolic foods are consumed, each with deep meaning:

- Matzah (unleavened bread): Symbolizes the haste of the Israelites' departure from Egypt; they didn't have time for their bread to rise. A powerful reminder of urgency and divine intervention.

- Maror (bitter herbs): Represents the bitterness of slavery endured by their ancestors.

- Charoset (sweet apple mixture): A reminder of the mortar used by the enslaved Israelites to build for the Egyptians, yet also a taste of sweetness and hope – a profound duality.

- Zeroa (lamb shank bone): Symbolizes the Paschal lamb sacrificed in the Temple, whose blood marked the homes of the Israelites for salvation during the tenth plague. This resonates deeply with Christian theology, as Jesus himself is often referred to as the "Lamb of God," whose ultimate sacrifice offers salvation.

- Karpas (a green vegetable, e.g., parsley): Dipped in salt water to represent the tears shed during slavery and the freshness of spring, symbolizing renewed hope and life.

This rich context shows that Jesus gathered his twelve closest apostles in an upper room in Jerusalem for a meal already laden with centuries of meaning, and what unfolded there was nothing short of pivotal. Picture this: the air is thick with anticipation, perhaps a little tension. Jesus, knowing his time is short, makes two earth-shattering announcements:

- He reveals that one of them will betray him. Can you imagine the shock? The immediate self-doubt, the whispers, the frantic questions around the table? Each disciple reacting in their own intensely human way. This sets the stage for the raw psychological drama Leonardo would later capture.

- He institutes the Eucharist (or Holy Communion). He takes bread, breaks it, and says, "This is my body, which is given for you." Then, he takes a cup of wine, saying, "This cup is the new covenant in my blood." It's an act of profound self-sacrifice and a promise of spiritual connection that has resonated for millennia.

This is truly a moment of intense emotional and spiritual density – a new covenant, a fresh agreement between God and humanity based on grace and redemption through Christ, echoing the ancient covenant of Passover. Unlike the Mosaic covenant, which emphasized adherence to the law and ritual observance, this new covenant, as described in passages like 1 Corinthians 11:23-26, Matthew 26:26-29, Mark 14:22-25, and Luke 22:14-20, centers on inner transformation, faith, and atonement through Jesus's sacrifice. It's about a deep, personal connection rather than strict rules, a concept I find myself grappling with in my own artistic process – how much structure do I need before I can truly express something raw and authentic, before I can make a truly personal connection with the canvas? The Gospels, penned by different authors for different audiences, each emphasize distinct aspects of this pivotal event: Matthew focusing on the fulfillment of prophecy, Mark on Jesus's suffering, Luke on inclusivity, and John on Jesus's divine identity and the intimate discourse at the table. Each offers a nuanced lens on the same earth-shattering meal.

Precursors to Leonardo: How Others Depicted The Last Supper

But how did we arrive at Leonardo's dramatic, human-centered interpretation? What came before, and why does his version feel so revolutionary? Leonardo's 'The Last Supper' stands out so dramatically because it broke from centuries of artistic tradition. Before him, depictions of this pivotal scene were often more static and formal, focusing on the ritualistic aspects rather than the explosive human drama. Earlier artists often adhered to established iconographic traditions, making their depictions feel more like solemn, almost tableau-like events. They were more concerned with conveying theological order and recognized symbols than with the raw, individualized psychological states of the figures. Let's look at a few notable examples, and consider how they compare to Leonardo's psychological depth:

Artist | Date & Location | Style & Approach | Key Differences from Leonardo | Symbolism in Earlier Works |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duccio di Buoninsegna | c. 1308-1311 (Siena Cathedral) | Part of the Maestà altarpiece, Duccio's Byzantine-influenced style emphasizes solemnity and iconic representation. Figures are arranged formally, often on one side of a long table, with minimal individual emotional expression. | More rigid, less naturalistic figures. Emphasis on theological order rather than individual psychological drama. Limited use of deep perspective. Judas is typically isolated, often seated on the opposite side of the table or with a darker complexion, clearly marking him as the outsider and betrayer, leaving no ambiguity for the viewer. | The isolation of Judas, his often darker complexion, and his position on the opposite side of the table serve as explicit visual cues to his role as the betrayer, leaving no room for doubt. |

| Giotto di Bondone | c. 1303-1305 (Scrovegni Chapel, Padua) | Giotto's frescoes, particularly in the Scrovegni Chapel, present a more traditional, almost medieval approach. His Last Supper depicts the apostles in a relatively solemn, linear arrangement. Emotional reactions are less individualized and more generalized. | Figures are more symbolic than psychologically real. Less dynamic interaction among the disciples. Judas is physically isolated, sometimes seated alone on the opposite side of the table or turning away, making his role explicitly clear to the viewer as the 'other' who stands apart from the faithful. The symbolism of isolation is paramount. | Judas is physically isolated, sometimes seated alone on the opposite side of the table or turning away, making his role explicitly clear to the viewer as the 'other' who stands apart from the faithful. The symbolism of isolation is paramount. |

| Andrea del Castagno | c. 1447 (Sant'Apollonia, Florence) | Castagno's Last Supper, a stunning fresco, shows a more advanced use of linear perspective than Giotto's, particularly in the architectural setting. However, the figures remain somewhat stiff and formal. | Improved perspective, but figures lack Leonardo's fluid movement and emotional range. Judas's isolation is explicit, not subtly woven into the group dynamic. | Judas is again explicitly isolated, seated on the near side of the table, making his role as the betrayer immediately visible and removing any doubt or tension about his identity. |

| Domenico Ghirlandaio | c. 1480 (Ognissanti, Florence) | Ghirlandaio's versions, common in Florentine refectories, are beautifully rendered frescoes. They often feature an elegant, almost courtly setting, with meticulous detail. While his figures are more naturalistic than earlier works, the disciples' reactions are still largely uniform. | More naturalistic but still lacks the explosive, simultaneous, and individualized emotional responses that characterize Leonardo's masterpiece. | Judas is typically a clear outsider, often physically separated or looking out at the viewer, symbolizing his detachment and impending treachery. The contrast between him and the other disciples is emphasized. |

Leonardo's genius lay in integrating Judas into the group, yet subtly highlighting his guilt through posture and shadow, making the moment of revelation intensely personal and psychologically charged for every figure present, not just the betrayer. He moved from a formal, theological depiction to a raw, human drama. It's a leap from simply illustrating a story to experiencing it through the emotional lens of each character. As an artist, I often look at these earlier works and appreciate their devotion and craftsmanship, but Leonardo's piece... that's where the story comes alive for me. It’s like the difference between reading a historical account and actually feeling the tension in the room. He transformed a solemn ritual into an active, unfolding event.

Leonardo's 'The Last Supper': A Masterclass in Human Drama and Innovation

With this profound biblical and historical backdrop in mind, we can now turn to how Leonardo da Vinci masterfully translated this pivotal moment into a visual tour de force. Leonardo's monumental mural, painted between 1495 and 1498 for the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, isn't just a religious icon; it's a psychological thriller wrapped in a devotional artwork. He chose that precise, explosive moment when Jesus announces, "One of you will betray me." The genius here is in capturing the aftermath – the ripple effect of that earth-shattering statement across the faces and gestures of the disciples. You can almost hear the gasps, the frantic whispers, the clatter of silverware. This wasn't merely a depiction; it was an invitation to experience the tension.

Every figure is a study in emotional response. They're not static, posed figures; they're alive, recoiling, questioning, gesturing, full of bewilderment and alarm. It's a masterclass in how to convey a narrative purely through human reaction, a hallmark of High Renaissance art. As an artist, I can tell you, achieving that kind of dynamic, individualized emotion is incredibly difficult, a testament to Leonardo's unparalleled observational skills and his lifelong study of human anatomy and expression. He understood that true feeling isn't always overt; it's in the subtle tilt of a head, the clenching of a hand, the widening of an eye. Leonardo's deep understanding of optics, anatomy, and even hydraulics (which informed his understanding of fluid movement) allowed him to render the human form and its reactions with astonishing realism and emotional resonance. He used subtle foreshortening – an artistic technique of portraying an object or view as closer than it is or as having less depth or distance, as an effect of perspective – to make individual figures feel more dynamically present and interacting with the viewer's space.

The Composition: A Stage for Emotional Resonance

Leonardo's composition is pure theatrical brilliance, a testament to his understanding of perspective. Jesus is, of course, the calm center, forming a stable triangle that anchors the entire scene. His outstretched hands point to the bread and wine, subtly referencing the Eucharist even amidst the chaos of the betrayal announcement. The disciples are grouped in threes, creating dynamic clusters that draw your eye across the table, each group reacting distinctively.

Notice the window behind Jesus? It's not just a window; it's a halo of natural light, subtly emphasizing his divinity without needing a traditional golden glow. It’s understated, powerful, and utterly groundbreaking for its time, showcasing Leonardo's mastery of subtle chiaroscuro – the use of strong contrasts between light and dark to create volume and drama, giving figures a three-dimensional quality and heightening emotional impact. Imagine how the shadows and highlights would have sculpted the disciples' expressive faces, making their shock and confusion almost palpable. It’s a bit like how I use color to create depth in my abstract work – a dark hue next to a vibrant one can make the latter pop, almost pushing it forward from the canvas.

The Setting and the Illusion: A Shared Meal

It's important to remember where 'The Last Supper' is located: the refectory, or dining hall, of a monastery. This wasn't a church altar, but a place where monks ate their daily meals in silence. The Santa Maria delle Grazie convent, commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza, was an active religious center, and placing such a profound scene in its dining hall was a deliberate act. By depicting Jesus's final meal on an illusionistic extension of their own dining space, Leonardo created a profound spiritual connection. The monks weren't just observing a painting; they were participating in a shared, sacred meal, making the divine narrative intensely present in their everyday lives. This thoughtful placement underscored the devotional purpose and spiritual contemplation intended by the artwork.

Leonardo's precise use of linear perspective, with the vanishing point directly behind Jesus's head, draws the viewer's eye into the painting and makes the refectory's actual architecture seem to seamlessly continue into the painted scene. This trompe-l'oeil (French for "to deceive the eye") effect was revolutionary. It didn't just fool the eye; it challenged the monks daily to reflect on the themes of loyalty, betrayal, and sacrifice as they broke bread, making them feel like witnesses to history unfolding at their own table. It’s like stepping into a story, rather than just reading it.

Leonardo's Revolutionary, Yet Problematic, Technique

One of the most fascinating (and heartbreaking) aspects of 'The Last Supper' is Leonardo's chosen technique. Unlike traditional fresco painting, where pigments are applied to wet plaster and absorbed into the wall, which requires rapid work and allows no corrections (think of painting on a wet cake, where every stroke is permanent), Leonardo opted for a method more akin to tempera or oil painting on a dry wall. He prepared the refectory wall with a double layer of gesso, pitch, and mastic – essentially treating it like an oil painting surface. Why? Leonardo was known for his perfectionism and his experimental nature; he desired to work slowly, add incredible detail, and achieve nuanced effects and luminosity impossible in true fresco. He wanted the ability to refine and correct, much like he would on a canvas. As an artist, I can absolutely relate to that desire for control and the ability to endlessly tweak, even if it means pushing the boundaries of the medium.

While this innovation gave us the masterpiece we know, it also led to its rapid deterioration. The paint began to flake within decades. The humidity and temperature fluctuations within the refectory, compounded by the unstable chemical bond between Leonardo's oil-based pigments (mixed with various binders like egg yolk, stand oil, or linseed oil) and the dry plaster, meant the mural quickly began to crumble. Specific pigments like lead white, often used for highlights, reacted poorly with the acidic oils in the binders, leading to a breakdown of the paint film and darkening over time. Vermilion, a vibrant red pigment, was also prone to blackening due to its sulfur content reacting with environmental factors and organic binders. This wasn't a true fresco, but a mural that showcased an artist's desire to push boundaries, even at a cost. We've lost so much of his original brushwork and detailing to time and previous, often damaging, restoration attempts. It makes you wonder, doesn't it, if the pursuit of perfection sometimes leads to its own undoing, a tragic reminder that materials have their limits? A tough lesson for any creative soul grappling with the permanence of their work. I’ve had my own experiments with unconventional materials in abstract art, and sometimes, you just have to accept that some ideas, however brilliant, aren't built to last forever.

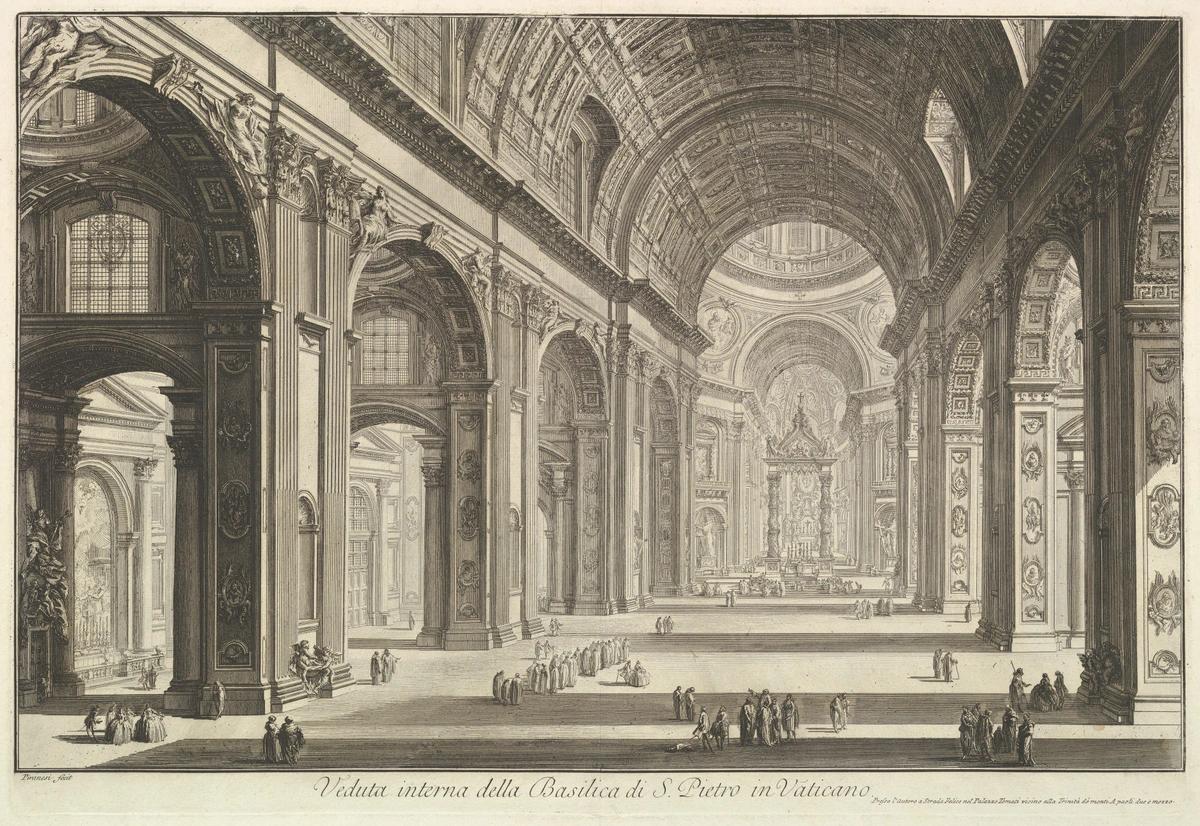

Above: A traditional, well-preserved Baroque fresco, demonstrating the long-lasting qualities Leonardo sought to bypass with his experimental technique.

The Key Players and Their Reactions: A Study in Psychological Realism

This is where Leonardo's psychological realism truly shines. He doesn't just paint generic figures; he imbues each disciple with a distinct, human response to Jesus's shocking announcement. It's an interpretation of The Last Supper figures that has rarely been matched in art history. Leonardo's keen observation of human emotion allows for a dynamic and engaging narrative, captured vividly in the grouping and gestures of the apostles. Let's look closely at the groups, moving from left to right, and truly feel their reactions:

Group (from left to right) | Disciples Represented | Emotional Response / Action | Key Details & Symbolism | Significance/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Group | Bartholomew, James the Less, Andrew | Astonishment, reaching out, questioning. Andrew raises his hands in protest, seeking clarity. | Bartholomew, at the far left, leans forward intently, almost standing, demanding answers, perhaps a direct explanation of this bewildering news. James the Less reaches out a hand to Peter, almost for reassurance or to convey a message. Andrew's gesture of raising his hands, palms outward, is a classic sign of 'hold on, what?' and innocence – an immediate, almost childlike, rejection of the accusation, highlighting his bewilderment. | Represents initial shock and a demand for clarification, a common human reaction to sudden, distressing news. Their gestures convey a plea for understanding and an innocent denial, establishing the emotional turbulence across the table. |

| Second Group | Judas Iscariot, Peter, John | The infamous trio. John swoons in distress; Peter leans in angrily, knife in hand (symbolic of later events in Gethsemane), and Judas, darker and recoiling, clutches a bag of silver, betraying his guilt. | John, traditionally depicted as the youngest and the "beloved disciple," almost collapses onto Peter, reflecting profound sadness and vulnerability. Peter, ever quick to anger and protective, holds a knife, foreshadowing his defense of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane – a symbol of his impetuous loyalty and readiness to act. Judas is the only one pulling back from Jesus, his face shadowed. The spilled salt cellar near his elbow is a traditional symbol of bad luck or betrayal. He clutches the bag of thirty pieces of silver, the price of his betrayal, making his motive tragically clear. | A powerful study in contrasting reactions: innocence and sorrow (John), fierce loyalty and protectiveness (Peter), and calculated, shadowy betrayal (Judas). Judas's subtle integration yet clear markers of guilt are a stroke of genius, making his treachery all the more poignant. |

| Central Figure | Jesus Christ | Calm, resigned, sorrowful. His open hands accept his fate, pointing to the Eucharist. | Jesus is the still point in a swirling storm of reactions. His serene, yet mournful, expression is central. His hands gesture towards the bread and wine, instituting the sacrament of the Eucharist even as betrayal looms. His gaze is directed forward, beyond the immediate drama, towards his ultimate sacrifice, embodying divine foresight. | The eye of the storm, embodying divine knowledge, sacrifice, and the institution of a new covenant amidst human chaos. His stillness emphasizes his divine foresight and acceptance, offering a poignant contrast to the apostles' turmoil. |

| Third Group | Thomas, James the Greater, Philip | Shock, inquiry, and self-doubt. Thomas points a finger upwards, questioning; James the Greater throws his hands wide in dismay, a powerful gesture of disbelief; Philip gestures to himself, asking, "Is it I?" | Thomas's raised finger might be a characteristic gesture (he's known for doubting), or a gesture towards heaven, questioning divine will or seeking divine intervention. James the Greater's widespread arms are pure, dramatic shock and dismay, an eloquent expression of profound disbelief. Philip's hand to his chest is an earnest, vulnerable self-interrogation, a moment of profound personal reflection and fear of unwitting guilt, perhaps even a plea of innocence. | Displays a range of responses from direct questioning (Thomas) to dramatic disbelief (James the Greater) and profound, personal self-reflection (Philip). These are deeply human reactions to an incomprehensible truth, showcasing the apostles' internal struggles. |

| Fourth Group | Matthew, Thaddeus, Simon the Zealot | Confusion and debate. Matthew and Thaddeus turn to Simon, seeking answers, perhaps unable to comprehend the announcement. | These three are engaged in a fervent discussion, seeking to understand. Simon, often depicted as a more outwardly passionate figure (a Zealot), might be seen as a natural recipient of questions, perhaps known for his firm opinions. Their huddle emphasizes collective bewilderment and the human tendency to seek communal understanding amidst chaos, to try and reason through the unreasonable, reflecting their struggle to process the news. | Highlights the human tendency to seek answers and debate amidst profound confusion and the inability to grasp a dire truth. They lean on each other for clarity, a universal coping mechanism in the face of the unfathomable. |

It’s a masterclass in psychological realism, wouldn't you say? Leonardo isn't just painting figures; he's painting souls, capturing the meaning of Jesus's last meal through their raw reactions. This level of emotional depth was revolutionary. Artists like Caravaggio would later build upon this dramatic approach to narrative, employing striking light and shadow to heighten emotional impact, drawing a clear lineage from Leonardo's groundbreaking work. My own abstract art often tries to evoke this kind of raw emotion, but it's much harder without the human figure as a direct vessel. You have to rely entirely on color and form, which is its own kind of challenge, a pure, distilled emotional expression.

The Profound Symbolism: Beyond the Masterpiece

'The Last Supper' is a treasure trove of symbolism in religious art, far beyond just the dramatic reactions of the disciples. Every detail, every gesture, contributes to a richer understanding of its spiritual significance. It's like looking at a piece of my own abstract art – what seems simple on the surface often has layers of hidden meaning waiting to be discovered, a quiet conversation if you know how to listen.

The Eucharist: A New Covenant and Sacrifice

At its core, the institution of the Eucharist is about sacrifice and spiritual sustenance. The bread represents Jesus's body, broken for humanity, and the wine his blood, spilled for the "new covenant" – a fresh agreement between God and humanity based on grace and atonement, rather than strict adherence to the law. For Christians, it's a ritual of remembrance, or more profoundly, anamnesis – a Greek theological term meaning to make present a past event, not merely to recall it. Through anamnesis, the original sacrifice is made real and accessible, connecting directly with Christ and offering spiritual nourishment, fostering an ongoing communion. It’s not just looking back at history; it’s making history present and active in one’s life.

This Eucharist meaning resonates deeply, becoming a central sacrament across diverse Christian traditions, from the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (where the bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ) to Protestant views of consubstantiation (where Christ is present with the elements) or symbolic remembrance. Each tradition grapples with the profound mystery in its own way, but the core act of self-giving remains. I often think about the profound simplicity of that act, yet its enormous weight. It's about giving oneself entirely, a concept I find myself returning to, pondering the boundaries of connection and offering in creation, much like how every brushstroke is a small part of my essence on display. How much vulnerability is too much? The Eucharist, as depicted here, is an ultimate act of self-giving, a concept I wrestle with in my own art – the balance between holding back and pouring your entire being onto the canvas.

Betrayal and Redemption: The Role of Judas

Judas betrayal symbolism is undeniably complex. His inclusion isn't just about highlighting evil; it’s about the very human capacity for temptation, sin, and the stark contrast that makes Jesus's sacrifice so profound. The darkness around Judas, his turning away, the spilled salt cellar – these are all subtle cues from Leonardo that tell his story without needing words. He clutches a bag of silver, the thirty pieces of silver, a clear symbol of his impending betrayal and avarice. His physical recoil from Jesus further isolates him, even though he is seated among the disciples. The contrast between his shadowed face and the reactions of the others is striking, a visual representation of his internal turmoil and external guilt.

But even in betrayal, there's the promise of redemption. Jesus knows, yet he still shares this meal. It's a testament to unconditional love and the belief that even in our darkest moments, there's a path back. Indeed, for Christian theology, Jesus's sacrifice on the cross was for all sins, including that of betrayal, making Judas's tragic role an integral, albeit dark, part of the larger narrative of salvation. A difficult path, sure, but a path nonetheless. This profound dichotomy makes 'The Last Supper' a powerful exploration of the human condition, grappling with both profound sin and boundless grace. It's a reminder that even the deepest vulnerability, like the raw emotion I explore in my 'unpleasant body' piece, can reveal a path to acceptance or understanding.

Foreshadowing and Prophecy

Beyond the immediate narrative, 'The Last Supper' is steeped in historical significance of The Last Supper, pointing to the future: Jesus's crucifixion, resurrection, and the establishment of the Christian church. It's a forward-looking piece, laden with prophetic significance. The gestures of Peter (with the knife) and Thomas (pointing upwards) have been interpreted as foreshadowing later events or pointing towards spiritual truths, such as Peter's defense of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane or Thomas's eventual doubt and affirmation of the resurrection. Even the calm triangle of Jesus's posture, contrasting with the chaotic disciples, can be seen as foreshadowing his divine acceptance of his fate. He is the anchor in the storm, fully aware of what is to come.

Lost Layers and Modern Interpretations

'The Last Supper' has also inspired numerous popular theories and interpretations beyond its theological and art historical significance. From speculative claims about a 'hidden message' or geometric patterns (like an 'M' shape supposedly for Mary Magdalene, a theory popularized by Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code) to modern fictional works, the painting continues to spark imagination. While it's tempting to search for secret codes, most of these theories lack academic support. The "M" for Mary Magdalene, for instance, is largely anachronistic and a misinterpretation of artistic conventions. Leonardo, like many Renaissance artists, often used triangular compositions and grouped figures in dynamic ways. Such an "M" shape is a coincidental visual artifact, a result of the arrangement of figures, not a deliberate hidden message. This theory, while compelling in its narrative, highlights the deep human desire to find deeper, secret meanings in such an iconic work, much like seeing faces in clouds; sometimes we want to believe there's a message meant just for us. It’s a wonderful example of how popular culture can imbue an artwork with new, albeit unfounded, narratives. Beyond fictional claims, it's also worth noting that due to the painting's early deterioration and subsequent restorations, much of Leonardo's original subtle details and layering have been lost to time. Art historians can only speculate about the precise vibrancy and minute brushwork that captivated its earliest viewers, based on early copies and preparatory drawings.

Later artists, too, have continued to grapple with the theme, from Tintoretto's dramatic, often darker, Baroque interpretations to Salvador Dalí's surrealist 'Christ in Perspective', showing how the foundational story continues to inspire varied artistic expression. It's fascinating how a single narrative can be endlessly reinterpreted through different artistic lenses, each revealing something new about the story and the artist – from ancient Byzantine mosaics, which prioritized solemnity and clear theological messages, to more contemporary street art pieces that might reinterpret the theme with modern social commentary.

Artistic Influences and Later Interpretations

Leonardo's 'The Last Supper' wasn't just a culmination of Renaissance ideals; it was a springboard for future artistic exploration. Its dramatic narrative and psychological depth profoundly influenced subsequent art movements, particularly Mannerism and Baroque art. Artists like Tintoretto, with his often darker and more dynamically composed 'Last Supper' (c. 1592-1594), and even Caravaggio, known for his dramatic use of tenebrism (a style of painting using very pronounced chiaroscuro, where there are violent contrasts of light and dark, and darkness becomes a dominant feature of the image) to heighten emotional intensity, built upon Leonardo's groundbreaking approach to human drama and narrative tension. These artists, reacting to or expanding upon the High Renaissance, often exaggerated emotional states or used heightened contrasts to engage the viewer in even more visceral ways. For example, Pontormo, a key Mannerist artist, might have taken the emotional intensity of Leonardo's figures and elongated them, or placed them in more contorted, unstable compositions, pushing the boundaries of naturalism to express spiritual turmoil. Caravaggio, on the other hand, would use tenebrism to spotlight the human vulnerability and raw, unidealized emotion of his figures, drawing the viewer into the sacred narrative with an almost brutal realism. It’s a testament to Leonardo’s original vision that it could inspire such diverse and powerful artistic responses.

Conservation and Controversies: The Ongoing Story

No discussion of 'The Last Supper' would be complete without acknowledging its tumultuous history. Because of Leonardo's experimental Renaissance painting techniques on a dry wall, the painting began to deteriorate almost immediately. Unlike true fresco, which binds pigments chemically to wet plaster (like those Baroque frescoes we saw earlier), Leonardo's oil and tempera mixture on dry plaster resulted in an unstable bond. The paint began to flake, peel, and lift away almost as soon as it was finished – within decades, not centuries. Beyond simple flaking, the mural also suffered from salt crystallization (from moisture wicking up the wall), blistering, mold growth, and extensive water damage over the centuries, accelerated by the refectory's inherent humidity and temperature fluctuations. It was, in many ways, doomed from the start due to a revolutionary technique that simply wasn't built to last.

Throughout the centuries, numerous attempts at restoration, some more damaging than helpful, were made. Everything from applying varnish to repainting sections occurred, often obscuring Leonardo's original brushstrokes and further weakening the fragile paint layers. These earlier interventions, often carried out by less skilled artists or with incompatible materials (like animal glue, oil-based paints, or even wax over Leonardo's delicate layers), added to the complexity and damage. It makes you realize how fragile art can be, and how easy it is to do more harm than good with the best intentions. Think of it like trying to fix a crumbling wall with mismatched materials – you might fill the hole, but you're not addressing the underlying structural problem, and you might even make it worse. Even vandalism, such as when Napoleon's troops used the refectory as a stable in 1796, inflicted further damage on the lower sections of the mural. The painting barely survived WWII when the building was bombed on August 15, 1943, protected only by sandbags, but still exposed to severe environmental stressors like vibrations and dust.

One of the most extensive and controversial restorations took place between 1978 and 1999, led by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon. This painstaking effort removed layers of previous overpaint, revealing more of Leonardo's original work than had been seen in centuries. The criteria for this monumental art conservation effort focused on:

- Removing previous, damaging interventions: Carefully stripping away centuries of additions, botched repairs, and incompatible materials that obscured the original, often through microscopic removal with scalpels and precision chemical solvents, informed by extensive laboratory analysis of paint samples.

- Stabilizing the remaining original paint: Using advanced chemical treatments and microscopic techniques to re-adhere loose paint fragments to the wall, literally gluing Leonardo's remaining brushstrokes back into place with specialized, reversible resins that wouldn't further degrade the artwork.

- Visually integrating areas of loss: Using a neutral watercolor technique called tratteggio (a system of vertical lines) to clearly distinguish new work from original, filling in gaps without trying to "recreate" Leonardo's hand or invent lost details. The goal was readability and visual cohesion, not reinvention. This allows the viewer to mentally fill in the blanks without being misled about what is original.

However, it also sparked intense debate among art historians and conservators. Critics argued that too much original paint had been lost (or removed during the cleaning process), or that the restored version was a mere echo of the original, raising fundamental ethical questions about the extent and philosophy of restoration. How much intervention is too much? Is it better to preserve a damaged original, or to "restore" it to a perceived past glory, even if it means some loss of the original or a subjective interpretation of what "original" means? These are the kinds of debates that keep me up at night when I think about the longevity of my own pieces, or what happens to them long after I'm gone. It's a delicate dance between preservation and interpretation, and sometimes, you just have to trust the experts to make the best call with the available science.

A Brief Timeline of 'The Last Supper's' Turbulent History:

- 1495-1498: Leonardo paints 'The Last Supper', commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza for the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

- Early 1500s: Signs of deterioration already evident due to the experimental technique.

- 1556: Giorgio Vasari, a contemporary art historian, notes the painting is "ruined," a stark testament to its rapid decay.

- 17th - 19th Centuries: Numerous, often amateur, restoration attempts involving heavy repainting and varnishing, often causing more harm than good and further obscuring Leonardo's original vision.

- 1796: Napoleon's troops use the refectory as a stable, causing further damage to the lower sections and overall neglect.

- 1943: The building is bombed during WWII; the painting survives, protected by sandbags, but is exposed to the elements and further environmental degradation.

- 1978-1999: Major scientific restoration led by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, a monumental effort to stabilize and reveal Leonardo's original work amidst intense scholarly debate.

- Present: Ongoing monitoring and highly controlled viewing conditions (limited visitors, precise climate control) to preserve the fragile masterpiece for future generations. Viewing is an experience in itself, requiring advance booking and timed entry to minimize environmental impact.

Why Does It Still Resonate?

So, why do we still pore over this painting, centuries later? Why does 'The Last Supper' continue to be a subject of fascination, study, and even debate? I think it boils down to universal human themes that transcend its religious context. It's truly a mirror for our own lives, our own struggles, and our own search for meaning. Can we truly understand loyalty without acknowledging the shadow of betrayal? I don't think so.

- Betrayal and Loyalty: Who hasn't felt betrayed, or perhaps, in a moment of weakness, betrayed another? Judas's internal struggle and external action resonate with our darkest fears and frailties, contrasted sharply with the fierce loyalty and protective instincts of other disciples. It's a primal story that plays out in grand narratives and quiet moments alike.

- Sacrifice and Forgiveness: The idea of giving oneself for a greater good, for an ideal, is timeless and deeply moving. Coupled with Jesus's implicit forgiveness, it speaks to our capacity for grace and the possibility of spiritual redemption. It's enough to make you need a strong cup of coffee, or perhaps, the sacrament itself!

- Community & Isolation: The gathering of individuals, even fractured by conflict and doubt, is a powerful image of human connection. Yet, Jesus stands somewhat isolated, accepting his fate with divine knowledge that sets him apart, creating a poignant tension between shared humanity and unique destiny – a kind of profound loneliness in his ultimate awareness.

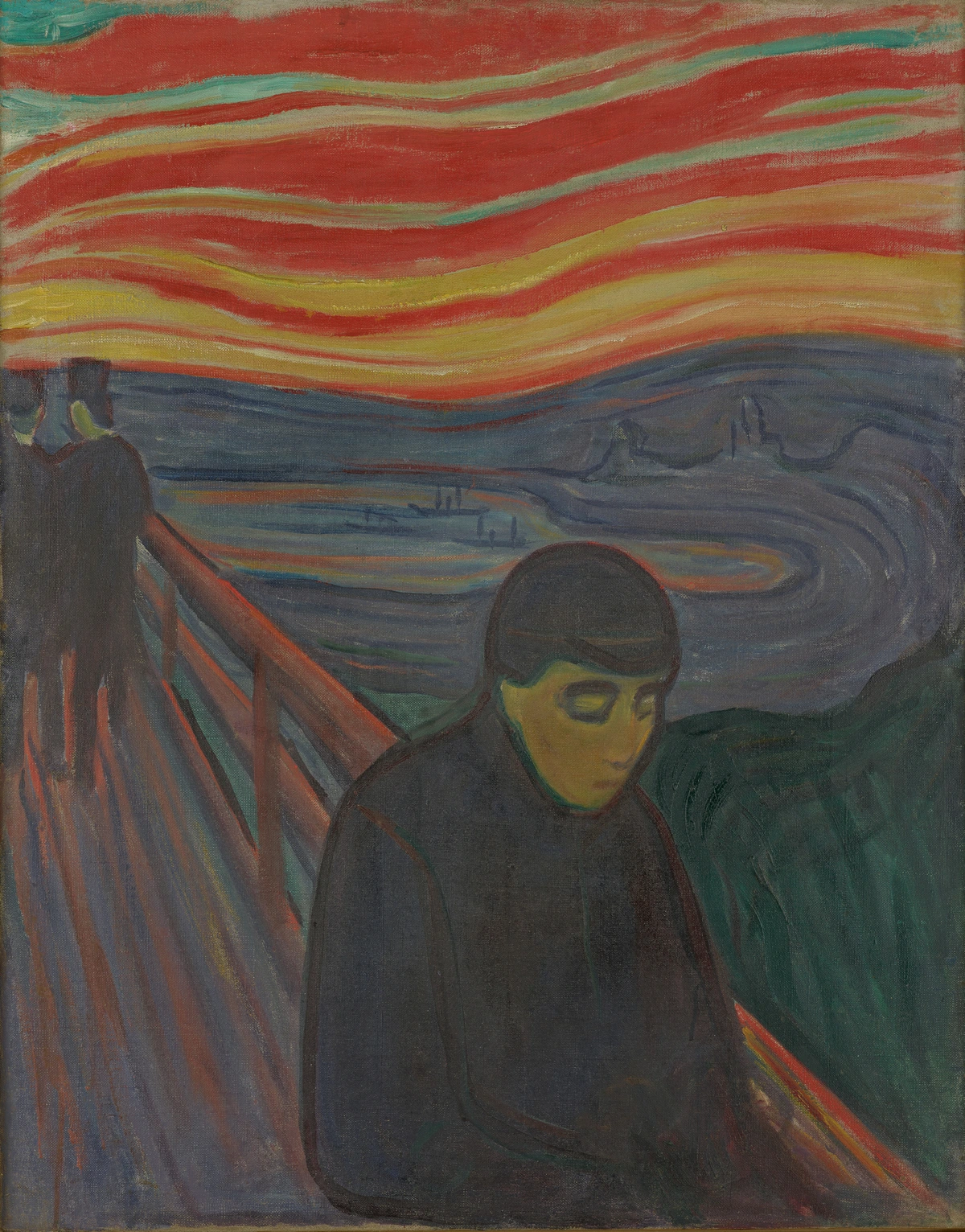

- The Unknown and Uncertainty: The disciples' reactions perfectly capture our own fear and uncertainty in the face of momentous, life-altering news – the sheer bewildering force of the unexpected. It's that gut-wrenching moment when the ground beneath your feet shifts, a feeling powerfully explored by artists like Edvard Munch, where even the sky seems to scream with uncertainty.

- Divine Love & Human Frailty: For believers, it's the ultimate expression of God's unconditional love for humanity, offering forgiveness and grace even in the face of ultimate betrayal, juxtaposed with the very human frailties of doubt, anger, and self-preservation that are so vividly displayed in the apostles' faces. It’s a profound exploration of the human condition and the enduring power of faith. This artwork's enduring presence in popular culture, from films to advertising and even internet memes, also testifies to its universal resonance. It's a piece of art that transcends its original context to become a shared cultural touchstone.

That's the real magic of art, isn't it? It speaks across time, across cultures, directly to the heart. It prompts us to ask: What moments have irrevocably shaped your life? How do you react when the ground beneath your feet shifts? What does sacrifice truly mean? This is what makes it an "ultimate guide" – not just telling you facts, but making you feel them.

Key Takeaways from 'The Last Supper'

If you only remember a few things about this masterpiece, let it be these essential points, the ones I always come back to when I think about this piece:

- Artist: Leonardo da Vinci, a master of the High Renaissance, known for his insatiable curiosity and experimental nature, and a profound understanding of human psychology and scientific principles.

- Date & Duration: Painted between 1495-1498 (nearly three years), commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza.

- Location: The refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, Italy. Its placement here fostered a profound, shared spiritual experience for the monks.

- Dimensions: Approximately 4.6 meters (15 feet) high and 8.8 meters (29 feet) wide.

- Subject: Jesus's final meal with his apostles, specifically the explosive moment he announces his betrayal and institutes the Eucharist (Holy Communion), set against the backdrop of a Passover Seder.

- Technique: An experimental method of tempera/oil on a dry wall, not a true fresco, which sadly led to its rapid deterioration due to unstable chemical bonds and environmental factors (e.g., lead white and vermilion pigments reacting with binders/humidity). This showcased Leonardo's desire for slow, detailed work but proved chemically unstable, requiring extensive art conservation.

- Innovation: Revolutionary for its psychological realism, dynamic composition, and vivid depiction of individual emotional responses among the disciples. It broke from earlier, more static depictions, creating a human drama and using advanced linear perspective and trompe-l'oeil effects, drawing the viewer directly into the scene. Leonardo's understanding of anatomy and optics was crucial here.

- Composition: Brilliant use of linear perspective and trompe-l'oeil to extend the room into the painting, placing the vanishing point behind Jesus, subtly highlighting his divinity. Disciples are grouped in dynamic threes, creating a sense of unfolding narrative. Mastery of chiaroscuro enhances emotional impact, and subtle foreshortening adds to the dynamism.

- Key Figures: Jesus (the calm center, accepting his fate), Judas (recoiling, clutching silver, spilled salt, a symbol of betrayal), Peter (angry, knife, symbolizing fierce loyalty), John (distressed and vulnerable), Thomas (questioning), Philip (self-doubting), each a master study in human emotion and a key element in the narrative of betrayal and redemption.

- Symbolism: Eucharist (bread/wine = body/blood, new covenant of grace, made present through anamnesis and central to doctrines like transubstantiation), betrayal (Judas's actions and isolation), and profound themes of sacrifice, redemption, and human frailty. The "M" for Mary Magdalene theory, while popular, lacks academic support and is a misinterpretation of compositional elements.

- Conservation: Subjected to extensive and controversial art conservation efforts due to its fragile original technique and centuries of damage (including war and neglect), highlighting ongoing ethical debates in restoration. The 1978-1999 restoration by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon was monumental in stabilizing the work and revealing more of Leonardo's original hand through meticulous techniques like tratteggio.

- Enduring Legacy: Continues to fascinate for its universal themes of loyalty, betrayal, sacrifice, and the human condition, far beyond its religious context. Its influence on later artistic movements like Mannerism and Baroque is undeniable, and its popular culture presence unwavering. It remains a cornerstone of Western art history, not least because it's a national treasure and not available on the art market.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Last Supper

As an artist who's spent time contemplating this masterpiece, and frankly, talking about it with countless other art lovers, I've encountered many of the same burning questions you might have. Here are some of the common ones that people often ask, and my take on them:

What is The Last Supper?

The Last Supper refers to the final meal that Jesus Christ shared with his twelve apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. During this meal, he prophesied his betrayal by one of his disciples (Judas Iscariot) and instituted the Eucharist (Holy Communion), a central sacrament in Christianity. This meal was a Passover Seder, imbuing it with deep Jewish historical and religious significance even before Jesus's reinterpretation as the "Lamb of God" whose sacrifice inaugurates a "new covenant." It's a story packed with layers, wouldn't you agree? A moment of profound spiritual and historical convergence.

Who painted the most famous 'The Last Supper'?

The most famous depiction of 'The Last Supper' was painted by the Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci. It's a mural (though technically not a true fresco, but rather tempera and oil on a dry wall) located in the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, Italy. When people talk about 'The Last Supper', this is almost always the one they're thinking of, and for good reason – it's a masterpiece of psychological insight and artistic innovation.

What are the main symbols in 'The Last Supper'?

Key symbols include:

- The bread (representing Jesus's body) and wine (representing his blood and the new covenant), symbolizing the Eucharist and Jesus's sacrifice. This is the heart of it – a ritual of making present, of anamnesis.

- Judas Iscariot's presence and actions (clutching a bag of silver, recoiling, the spilled salt cellar) symbolize betrayal, sin, and avarice – the darker side of human nature, a necessary shadow to highlight the light.

- The light behind Jesus, emanating from the window, subtly hints at his divinity and unique role, a quiet halo of truth, contrasting with the dramatic chiaroscuro on the disciples.

- The dynamic grouping of the disciples highlights their individual psychological responses to the shocking announcement, showing humanity in all its messy, emotional glory – from shock to anger to denial.

- The placement of the meal in a refectory, an illusionistic extension of the monks' dining space, connects the divine narrative directly to their daily spiritual life, making it intensely personal through trompe-l'oeil.

Where is Leonardo da Vinci's 'The Last Supper' located?

Leonardo da Vinci's iconic mural is housed in the refectory (dining hall) of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, Italy. Due to its extremely fragile state, viewing is highly controlled and requires advance booking. It's a true pilgrimage for many art lovers, and absolutely worth the effort if you get the chance – but remember, you'll need to plan ahead! You can't just walk in, much like you can't just walk into the Uffizi without a ticket!

How long did it take Leonardo to paint 'The Last Supper'?

Leonardo da Vinci worked on 'The Last Supper' for approximately three years, from 1495 to 1498. His experimental technique, which allowed him to work slowly and make changes, contributed to this extended timeline, but also, unfortunately, to the painting's rapid deterioration.

What are the dimensions of 'The Last Supper'?

The mural is impressively large, measuring approximately 4.6 meters (15 feet) high and 8.8 meters (29 feet) wide. This colossal scale adds to its immersive quality, making the scene feel like an extension of the refectory space itself.

Which apostles are depicted in 'The Last Supper'?

All twelve apostles are depicted, grouped in fours from left to right, flanking Jesus:

- Group 1 (far left): Bartholomew, James the Less, and Andrew.

- Group 2 (left of Jesus): Judas Iscariot, Peter, and John.

- Group 3 (right of Jesus): Thomas, James the Greater, and Philip.

- Group 4 (far right): Matthew, Thaddeus, and Simon the Zealot.

Each is rendered with distinct emotional and physical reactions, making the painting a powerful study in human psychology.

What is the significance of Judas in 'The Last Supper'?

Judas Iscariot's role is crucial as the betrayer of Jesus. His depiction highlights the human capacity for sin and temptation, but also sets the stage for Jesus's ultimate sacrifice and the themes of redemption that are central to Christian theology. He serves as a powerful contrast to the other devoted apostles, emphasizing the profound moral choice inherent in faith and loyalty. His presence underlines the concept that even within the most sacred circles, human frailty can lead to profound betrayal, yet this betrayal ultimately facilitates divine grace. It's a harsh truth, but an integral part of the narrative, revealing the depth of both human darkness and divine light. Without Judas, the story of sacrifice and redemption wouldn't have the same profound impact, would it?

Why is 'The Last Supper' considered so important?

'The Last Supper' is considered important for several reasons, and honestly, each one is a profound rabbit hole to explore:

- Artistic Innovation: Leonardo's revolutionary use of perspective, psychological realism, and experimental painting techniques made it a groundbreaking work of Renaissance art. It moved away from static, formal religious scenes to a dynamic human drama. He truly broke the mold, ushering in a new era of emotional depth and narrative painting, drawing on his scientific studies of anatomy and optics.

- Religious Significance: It depicts the pivotal moment of the institution of the Eucharist and the prophecy of betrayal, central events in Christian theology that continue to be reenacted today. It's a cornerstone for believers worldwide, capturing a foundational sacrament.

- Human Drama: It captures a universal human drama of shock, denial, and questioning, making it relatable across cultures and beliefs, speaking to timeless themes of loyalty, treachery, and sacrifice. We see ourselves in those reactions, in that moment of crisis, a mirror to our own vulnerabilities.

- Influence: It has profoundly influenced countless artists, interpretations, and religious thought for centuries, becoming one of the most recognized and reproduced artworks globally, inspiring everything from Mannerist exaggerations to surrealist homages. Its shadow is long and deep, stretching through art history and popular culture.

- Conservation History: Its troubled history and numerous art conservation efforts also make it a significant case study in the challenges of preserving artistic heritage. It's a constant battle against time, a testament to humanity's desire to cling to beauty and meaning, even in the face of near-total loss. As a national treasure, it is not available for sale on the art market, further solidifying its unique and protected status.

My Final Thoughts...

Leonardo's 'The Last Supper' remains a paramount artwork due to its brilliant synthesis of religious narrative, human psychology, and artistic innovation. It is a testament to the power of art to capture a single, intensely human moment with such psychological insight that it transcends centuries and continues to speak directly to the human condition. For me, looking at 'The Last Supper', I'm always struck by how a single, intensely human moment, captured with such psychological insight, can contain so much. It's a reminder that even in moments of profound sadness or betrayal, there's deeper meaning, a larger narrative unfolding.

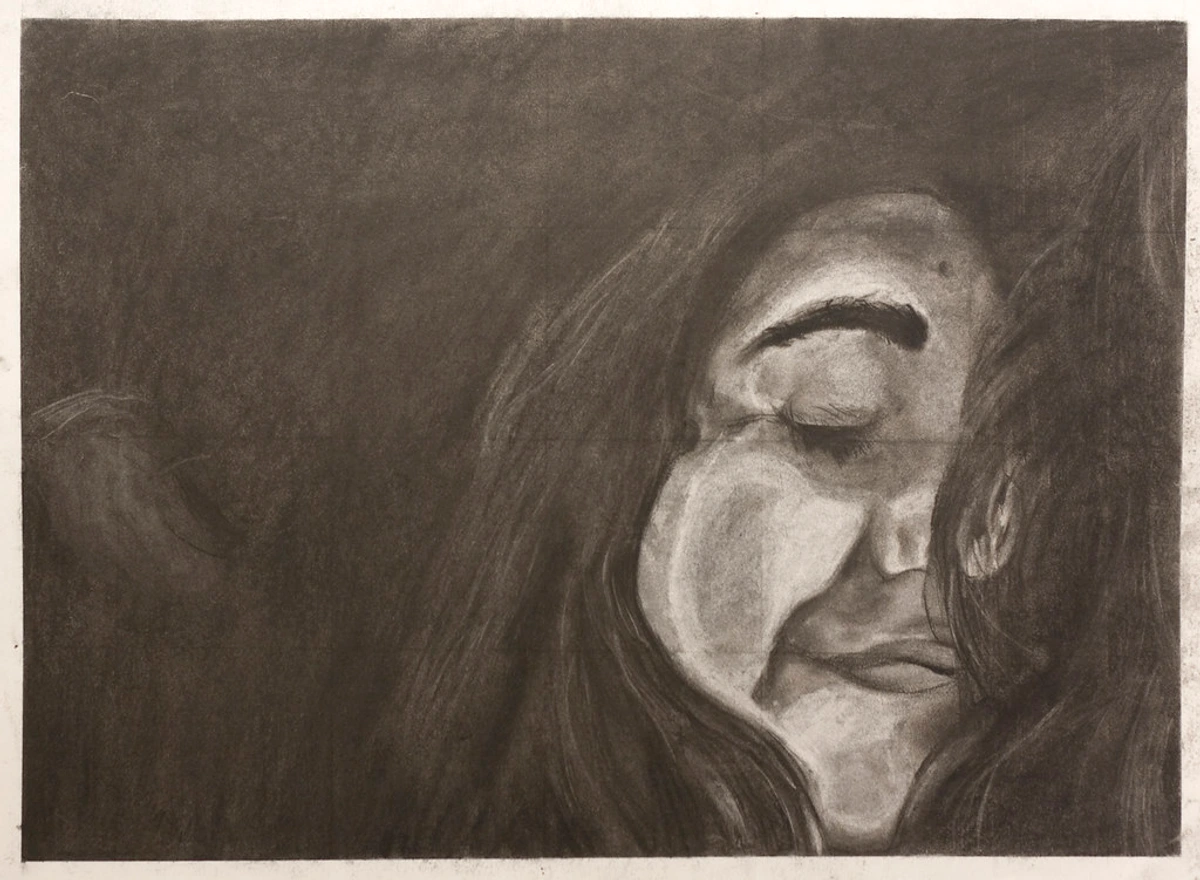

This piece, for all its grand scale and historical weight, resonates deeply with my own artistic journey. The struggle to convey raw emotion, the vulnerability of placing one's essence onto a canvas, the tension between holding back and pouring your entire being into a creation – these are universal artistic dilemmas. Much like Leonardo captured the internal worlds of his apostles, I strive to capture complex inner states in my abstract work. Take my 'Monster with Reflection' piece, for example. It's about confronting the self, accepting one's inner complexities, and finding a serene smile amidst disquiet – a journey not unlike the path of understanding and redemption woven through 'The Last Supper'. The most profound truths, I believe, often lie just beneath the surface, waiting for us to truly look, to truly feel.

And perhaps, that's a journey we can all take, whether in front of a masterpiece or a contemporary piece in a Den Bosch museum. The conversation, after all, is forever. If you want to dive deeper into art history and see how artists grapple with these big themes across time, you might enjoy exploring some other great artists or art movements on the site. Thank you for joining me on this journey through one of art's most enduring puzzles: How does art, like a frozen moment in time, continue to speak to our deepest human truths? What hidden narrative does your own life tell, and how will you choose to paint it?

Further Reading and Exploration

To deepen your understanding of 'The Last Supper' and related topics, consider exploring these resources:

- "Leonardo da Vinci" by Walter Isaacson: A comprehensive biography that delves into Leonardo's life, his insatiable curiosity, and his artistic and scientific endeavors, offering insight into the mind behind the masterpiece.

- "The Private Lives of the Impressionists" by Sue Roe: While not about Leonardo, this offers insight into the human stories behind iconic art, much like we've explored the emotions in 'The Last Supper', revealing the personal struggles and triumphs of artists.

- "The Da Vinci Code" by Dan Brown: A work of fiction that, despite its historical inaccuracies regarding the painting, popularized many discussions about its supposed hidden meanings and continues to engage readers with its speculative narrative. It's a fascinating look at how art can inspire new stories, even if they're not factual.

- The Official Santa Maria delle Grazie Website: For detailed information on visiting the actual site and the current conservation efforts, including precise climate control and visitor limitations. This is your go-to for planning a real-life encounter with the work.

- Academic Journals: Search for art history journals on databases like JSTOR for scholarly articles on Renaissance art, Leonardo's techniques, and the history of art conservation. These offer in-depth, peer-reviewed perspectives, delving into the scientific and historical complexities.

- Documentaries on Leonardo da Vinci: Explore films or series that delve into his life and works, offering visual context and expert analysis of his methods and impact.

- Museum Exhibition Guides: Often, major museums will publish extensive catalogs for exhibitions on Renaissance masters, providing specialized essays and high-quality reproductions that can offer fresh insights into 'The Last Supper' and its contemporaries.