William Kentridge: My Personal Journey Through Charcoal, Erasure, and Memory

Dive deep into the world of William Kentridge through a personal lens. Explore his unique charcoal animations, powerful themes shaped by apartheid and identity, diverse media (prints, theatre, installations), influences, and where to experience his compelling art.

William Kentridge: My Personal Journey into the World of Charcoal, Erasure, and Memory

There are some artists whose work just gets you, right? It bypasses the brain and hits you somewhere deeper. For me, William Kentridge is one of those artists. I remember the first time I saw one of his charcoal animations – it was Mine, part of the 9 Drawings for Projection series. Watching the drawing constantly shift, figures appearing and dissolving, felt like watching thoughts take shape, dissolve, and reform. It was a visual stream of consciousness that mirrored my own sometimes-messy thinking process, and honestly, it made me feel seen, in a strange, artistic way.

His work isn't always easy – it's often layered with history, politics, and a profound sense of melancholy – but it's undeniably human and utterly compelling. This isn't just a dry biography; it's my attempt to share what makes Kentridge's work so special, from his unique artistic methods to the powerful stories he tells across various media. Think of it as a friend walking you through an exhibition, pointing out the things that resonate most, maybe getting a little lost in thought along the way.

Who is William Kentridge, Anyway? A Life Shaped by History and Thought

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1955, William Kentridge grew up during the height of apartheid. This historical context is absolutely crucial to understanding his art. It wasn't just a backdrop; it was the air he breathed, the system that shaped the lives around him, and the source of much of the tension and injustice he witnessed. His family history is also significant; his parents were prominent anti-apartheid lawyers, exposing him early to the complexities of justice, power, and resistance. This background in law and activism, coupled with his later training in politics and African studies before studying fine art, deeply informs his perspective. You can see the echoes of that academic grounding in history and power structures throughout his career, giving his artistic voice a unique weight and perspective. It makes me think about how our own backgrounds, even seemingly unrelated ones, inevitably seep into our creative output, shaping the very way we see and interpret the world. He's not just an artist; he's a storyteller, a historian, and a philosopher, all rolled into one.

He's known for a diverse range of media, including drawing, printmaking, sculpture, film, and opera direction. He's also gained significant international recognition, with major retrospectives at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and prestigious awards like the Praemium Imperiale, solidifying his place as one of the most important contemporary artists working today. His work is held in major collections worldwide, a testament to its global impact despite its specific South African roots. It's fascinating how art rooted in a very specific local history can speak so powerfully to universal human experiences.

My Fascination with Charcoal, Erasure, and Ghosts

This is where Kentridge's work truly captivated me. His approach to charcoal animation is unlike anything else. Instead of creating thousands of individual drawings for an animation, he makes a single drawing, photographs it, then alters it slightly by erasing and redrawing elements, photographing the changes, and repeating the process. The final film shows the drawing constantly shifting, with ghosts of previous marks and erasures visible. It's like watching a drawing think, or perhaps more accurately, watching a memory being formed, distorted, and recalled. The visible traces of charcoal dust and faint lines left behind by the eraser create a palpable sense of history and the passage of time directly on the image. It's a process that feels incredibly honest, vulnerable even. It shows the work, the mistakes, the changes of mind. It's like seeing the artist's brain at work, the layers of thought and revision.

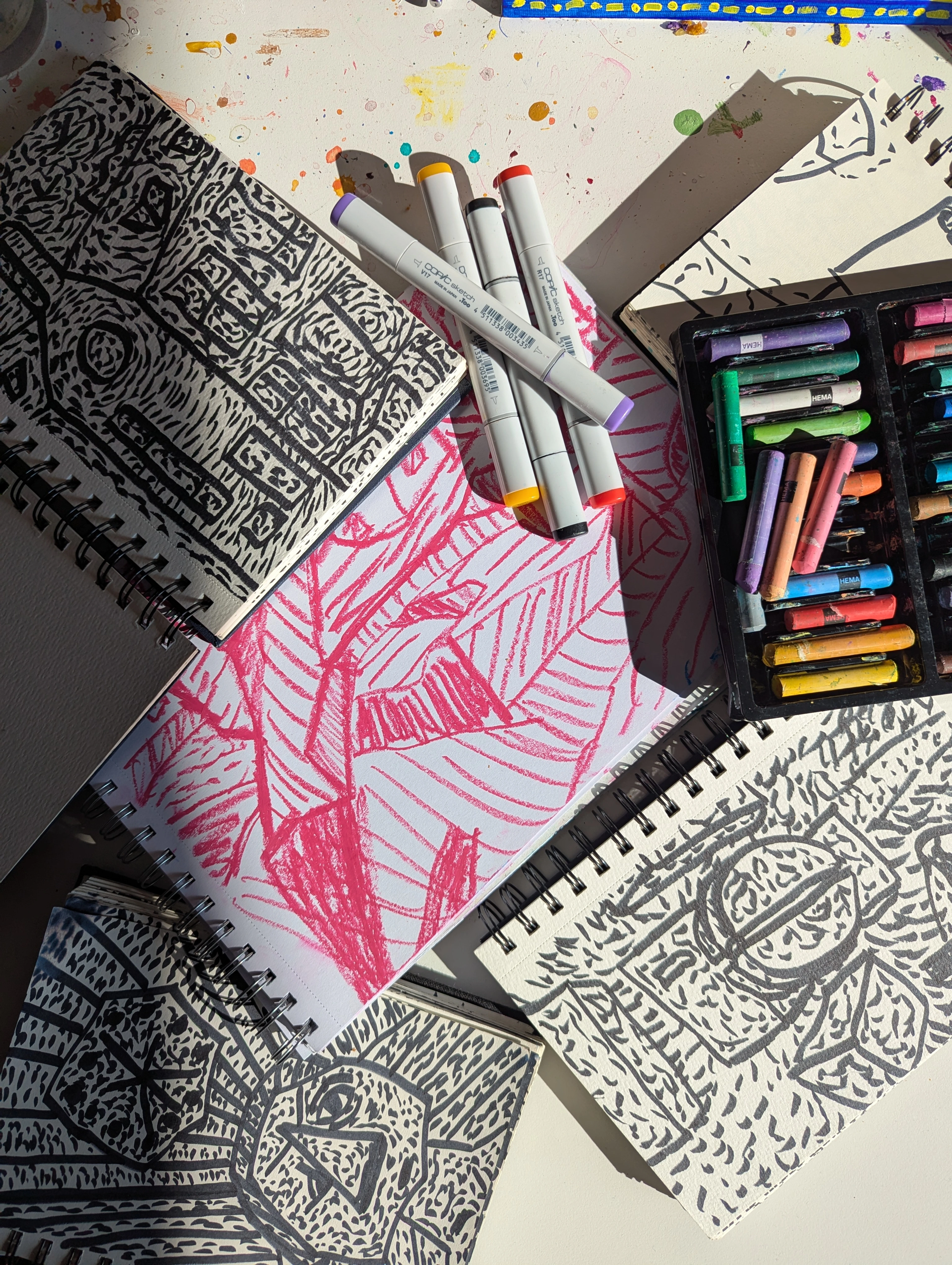

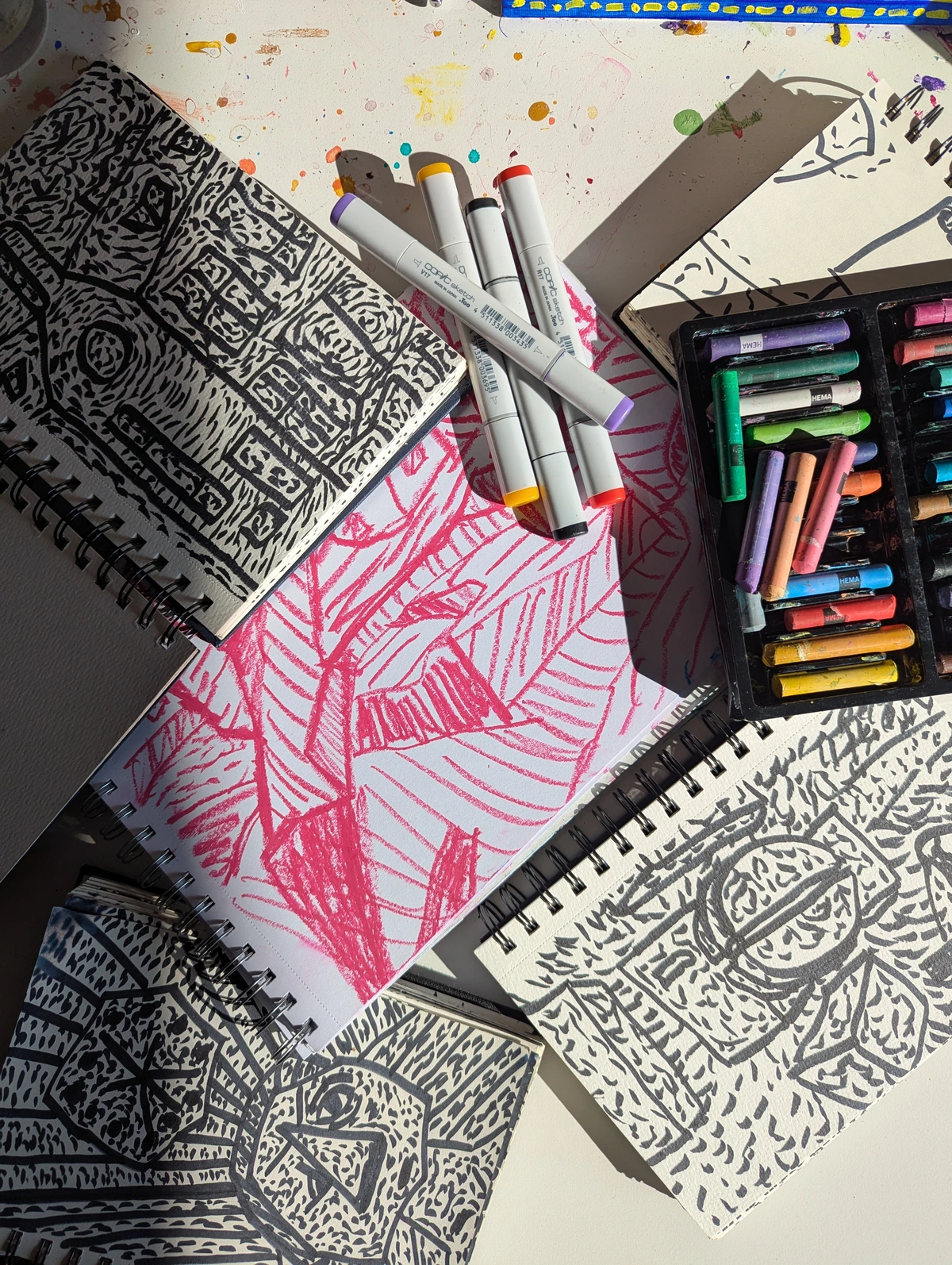

Imagine sitting with a piece of charcoal, sketching out an idea. You make a mark, decide it's not quite right, smudge it, redraw it. Kentridge does this, but each stage of that messy, evolving process is captured. The erasures aren't hidden; they become part of the visual narrative, faint traces of what was there before. This is what makes it feel like a visual stream of consciousness – the constant flux, the visible history of its own making. It reminds me a bit of my own studio floor, covered in discarded sketches and smudges – a visible history of creative struggle, perhaps? Though his is, you know, art.

This technique perfectly embodies his themes of memory, history, and the way the past is never truly gone but leaves its traces on the present. It makes you think about your own creative process, doesn't it? All those sketches and ideas that get rubbed out or painted over, but still inform the final piece. It's a powerful form of visual storytelling.

Key works like the 9 Drawings for Projection series (which includes films like Mine, Monument, and Felix in Exile) showcase this technique beautifully. Other notable early animations include Sobriety, Obesity & Growing Old and History of the Main Complaint. Mine, for instance, depicts the harsh realities of mining and labor under apartheid through the eyes of the industrialist Soho Eckstein, his world literally shifting and dissolving around him. Soho Eckstein often represents the white capitalist class, navigating a world built on exploitation, often depicted in a suit, sometimes with a megaphone or other symbols of power. Felix in Exile introduces Felix Teitelbaum, a more introspective figure, often seen as an artist or intellectual, whose journey through a scarred landscape is haunted by the erased figures of those displaced or killed. Felix is typically shown nude or vulnerable, a stark contrast to Soho. These recurring characters often feel like alter egos or archetypes, allowing Kentridge to explore different facets of the South African experience and the human condition. Watching these figures navigate landscapes scarred by industry and history, constantly shifting and reforming through charcoal and erasure, is a profound experience. It's like the landscape itself has a memory, and Kentridge is making it visible. Beyond these early works, his moving image practice has evolved, incorporating collage, live-action footage, and more complex layering, seen in later works like The Refusal of Time (2012), a multi-channel video installation that delves into the history of timekeeping, colonialism, and physics, featuring a complex interplay of sound, image, and kinetic sculpture.

The Stories His Art Tells Me: Themes That Resonate Deeply

Kentridge's work is deeply rooted in his South African context, but its themes are universal, speaking to the human condition in ways that transcend geography. He explores:

- History and Memory: How the past shapes the present, the unreliability of memory, and the weight of historical trauma (particularly apartheid). In films like Felix in Exile, the landscape itself seems to hold the memories of violence and displacement, the erased figures leaving ghostly impressions on the land. He often references specific historical events, like the Sharpeville massacre (where police killed peaceful protestors in 1960) or the forced removals under the Group Areas Act (which segregated residential areas by race), embedding the broader political narrative within his personal, visual language. The way he layers and erases feels like the way history itself is constantly being rewritten, with inconvenient truths smudged but never fully gone. It's a powerful reminder that history isn't static; it's a living, breathing, messy thing.

- Politics and Power: Critiques of oppression, bureaucracy, and the absurdities of power structures. His early Soho Eckstein films often satirize the world of the white industrialist during apartheid, highlighting the moral compromises and blindness of the era. He doesn't shy away from depicting the mechanisms of control, often using imagery of typewriters and bureaucratic documents. This theme of oppressive systems feels particularly resonant today, doesn't it? It makes you wonder how much has really changed, or how the 'erasures' of history continue in different forms globally.

- Landscape and Place: The South African landscape isn't just a backdrop; it's a character, scarred by history and reflecting the human condition. The mines, the dusty plains, the urban spaces – they are imbued with the weight of the past and the ongoing struggles of the present. It's a powerful idea, that the land itself can hold trauma and memory.

- Identity and The Self: Explored through his recurring characters like Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitelbaum, who can be seen as different aspects of the artist or archetypes representing societal roles, internal conflicts, and the search for identity within a fractured history. Their interactions and transformations reflect the complexities of selfhood shaped by external forces and internal landscapes.

- The Studio as a Metaphor: His studio, often depicted in his work (sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically), becomes a space of thought, creation, and grappling with the world. It's where the messy process happens, where ideas are born, erased, and reborn. It makes me think about my own studio – that chaotic, sacred space where ideas wrestle with materials, where mistakes are made and sometimes kept, sometimes erased, but always part of the journey. It's a universal artist experience, I think, that wrestling match with the blank page or canvas.

- Process and Transformation: The act of making, changing, and the constant state of flux. This is inherent in his animation technique but also a broader theme about personal and societal change – how we are constantly being redrawn by our experiences. It's a hopeful idea, perhaps, that change is always possible, even if the past leaves its marks.

His use of symbolism is rich, often featuring recurring motifs like coffee pots (representing domesticity and perhaps the mundane amidst turmoil, a quiet counterpoint to the political chaos), typewriters (bureaucracy, control, the oppressive weight of officialdom), and figures walking in procession (migration, protest, the weight of history, the endless movement of people). He also frequently incorporates text, maps, and found imagery directly into his drawings and prints, layering information and history onto the visual surface, much like the layers of memory or bureaucracy he depicts. It's like learning a visual language that speaks volumes about the human experience, often with a melancholic, poetic tone. For me, the theme of memory and erasure resonates most deeply – the idea that the past is never truly gone, just layered over, feels incredibly true to life and my own creative process.

Beyond the Drawing Board: Prints, Theatre, and Installations

While the animations are perhaps his most famous, Kentridge is also a prolific printmaker. He works in various techniques like etching, engraving, lithography, and linocut. His prints often share the same visual language and thematic concerns as his drawings and films, exploring layering, fragmentation, and the interplay of positive and negative space. Techniques like etching, where lines are incised into a metal plate using acid, or linocut, where areas are carved away from a linoleum block, inherently involve processes of removal and mark-making, echoing the erasure central to his animation work. It's fascinating how he finds ways to explore the same core ideas through different materials and processes. A notable print series is Portage, which features figures carrying burdens, linking back to themes of migration and labor.

Printmaking, like his animation, is a process of layering and transformation. It feels fitting for an artist so concerned with process and the accumulation of marks. If you're interested in starting an art collection, prints by established artists like Kentridge can sometimes be a more accessible entry point than unique works. Understanding the different types of prints – from limited editions to artist's proofs – can be a whole journey in itself, affecting value and desirability. You can learn more about buying art prints and understanding limited editions if that piques your interest.

But his practice extends even further. Kentridge has gained international acclaim for his direction of opera and theatre productions, bringing his distinctive visual style, animations, and thematic depth to the stage. Notable productions include Shostakovich's The Nose (known for its striking visual metaphors and use of animation), Berg's Wozzeck (exploring themes of social injustice and alienation), and his own interpretation of Beckett's Waiting for Godot. A significant aspect of these productions is his long-standing collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company, where puppetry becomes another powerful tool for storytelling and embodying characters, adding a unique, often poignant, physical dimension to his narratives. These productions are massive undertakings, often involving large teams and collaborations, highlighting another dimension of his creative process – working with others to bring complex visions to life. It's a huge leap from the solitary act of drawing in a studio, isn't it? The scale and collaborative nature must be a completely different kind of energy.

His large-scale installations, often combining film projections, sound, sculpture, and performance, create immersive environments that envelop the viewer in his world of shifting histories and fragmented narratives. Think of his monumental processional performance and installation The Head & the Load (2018), which explored the forgotten history of African porters in WWI, using shadow play, projections, live music, and performers carrying silhouetted burdens to create a truly overwhelming and moving experience. Or More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015), a multi-channel video installation featuring a procession of figures, both human and animated, moving across the screens, evoking themes of migration, displacement, and the fragility of life. It's hard to imagine the sheer scale and impact of something like that without seeing it.

He also creates large-scale sculptures and tapestries, demonstrating his ability to translate his drawing and thematic concerns into different physical forms. His tapestry series, like the Porter Series, directly translates imagery from his drawings and films into woven form, adding a tactile dimension to the familiar figures and landscapes. His influences are wide-ranging, from early cinema and animation pioneers like Georges Méliès (whose fantastical, hand-drawn films share a sense of wonder and transformation) to artists like Francisco Goya (whose dark, satirical prints like The Disasters of War resonate with Kentridge's political commentary) and Honoré Daumier (known for his caricatures and social critique). You can see echoes of German Expressionism in his figures and landscapes (the distorted forms, the emotional intensity), and a deep engagement with theatre and literature throughout his career. He often collaborates with composer Philip Miller, whose scores blend classical, jazz, and African musical traditions, adding another layer of historical and cultural resonance to the visuals, often creating a haunting or melancholic atmosphere that perfectly complements the visuals. It's a rich tapestry of influences, much like his layered art. He also engages with the academic world, giving lectures and writing, further demonstrating the intellectual depth underpinning his artistic practice.

Experiencing Kentridge's Work

Seeing Kentridge's work in person is a different experience than seeing it online or in books. The scale of his drawings (some are surprisingly large!), the immersive nature of his installations (which often combine film, sound, and objects), and the quiet power of his prints really come alive in a gallery or museum setting. The soundscapes and music in his films, often created in collaboration with composer Philip Miller, are integral to the emotional impact. Miller's scores often blend classical, jazz, and African musical traditions, adding another layer of historical and cultural resonance to the visuals, often creating a haunting or melancholic atmosphere that perfectly complements the visuals. It's not just something you see; it's something you feel.

I remember seeing a large-scale installation of his work, where the animations were projected onto multiple screens, surrounded by related drawings and objects. The sheer scale and the enveloping sound felt overwhelming in the best possible way – it wasn't just looking at art, it was stepping into a world, feeling the weight of the history he depicted. The sound, in particular, added a layer of emotional depth that print or static images can't replicate. It's an experience that stays with you.

You can find his work in major museums and galleries around the world, such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Keep an eye out for exhibitions – they are often beautifully curated and offer a deep dive into his practice. Exploring art galleries and museums worldwide is one of my favorite ways to spend a day, and finding a Kentridge piece is always a highlight. If you can't see his work in person, look for documentaries or interviews online; hearing him talk about his process can be incredibly insightful. It's like getting a peek behind the curtain of that fascinating mind.

Collecting William Kentridge

If you're drawn to Kentridge's work and considering adding it to your collection, his prints are often the most accessible option. Original drawings and sculptures command much higher prices, as you might expect. Kentridge is particularly known for his etchings, lithographs, and linocuts, often produced in limited editions. While prices vary greatly depending on the technique, size, edition size, and subject matter, entry-level prints might start in the low thousands of dollars, while major works can reach six or even seven figures at auction. Research is key – understand the different print techniques (etching, lithograph, screenprint), editions (limited editions, artist's proofs, states), and provenance. Don't be afraid to ask questions about the state of the print or the edition size; these details matter and can significantly impact value. Factors like the condition of the print, the rarity of the edition, and the artist's market trends all play a role in pricing.

Buying from reputable galleries or auction houses is always recommended. If you're new to collecting, guides on how to buy art or where to buy art can be really helpful. And remember, collecting is a personal journey – buy what you love and what resonates with you. It's not just about investment, though that can be a factor (art as an investment is a whole other conversation!). Ultimately, owning a piece is about living with something that moves you. My dream Kentridge piece? Probably a small, early charcoal drawing with visible erasures – something that really shows the hand and the process. It's that connection to the making that I find so compelling.

My Takeaway: Process, Memory, and the Urge to Draw

William Kentridge's work is a powerful reminder that art can be both deeply personal and profoundly political. It shows us that process is as important as the final product, and that even in erasure, traces remain. His ability to weave together history, memory, and the act of drawing is simply masterful. It inspires me in my own work, reminding me that the layers and imperfections are part of the story. I remember seeing his work and thinking about how my own sketches, the ones I discard or draw over, aren't failures but necessary steps, visible or not, in the final piece. It made me appreciate the journey as much as the destination. It made me look at my own messy studio with a little more kindness, seeing the history of ideas in the smudges.

It makes me think about my own timeline as an artist, the moments of creation and the moments of doubt or change, all contributing to the larger picture. And honestly, sometimes just looking at his work makes me want to grab a piece of charcoal and just draw. To embrace the mess, the smudges, the possibility of change. It's a powerful urge, isn't it? To just make marks, knowing they can be changed, but their ghosts will linger. What about your own creative process? Do you see the history of your making in your work?

FAQ: Your Questions About William Kentridge

What is William Kentridge's most famous work?

While it's hard to pick just one, his charcoal animations, particularly the early ones featuring the characters Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitelbaum (like Mine or Felix in Exile), are arguably his most iconic and widely recognized works.

What themes does William Kentridge explore?

He primarily explores themes related to his South African background, including apartheid, history, memory, colonialism, and the political landscape. He also delves into universal themes like time, process, transformation, identity, and the nature of the human condition.

What media does William Kentridge use?

Kentridge is known for his versatility. He works extensively with charcoal drawing, which forms the basis for his stop-motion animations. He is also a significant printmaker (etching, lithograph, linocut), creates sculptures, tapestries, and directs opera and theatre, often collaborating with the Handspring Puppet Company. His moving image work also incorporates collage and live-action.

Where can I see William Kentridge's art?

His work is held in major museum collections worldwide, including institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. He also has exhibitions in galleries globally. Checking the websites of major modern art galleries and museums worldwide is a good starting point.

Is William Kentridge still alive?

Yes, William Kentridge is alive and continues to be an active and influential artist.

How did apartheid influence William Kentridge's art?

Growing up during apartheid profoundly shaped his themes. The political system's injustice, violence, and forced segregation are directly addressed in his work through allegorical narratives, depictions of scarred landscapes, and the very process of erasure and redrawing, which mirrors the attempts to erase history or memory. His family's background in anti-apartheid law also deeply informed his perspective.

What is William Kentridge's studio like?

Kentridge's studio is often depicted as a space of creative chaos, filled with drawings, materials, and objects. It's central to his work, not just as a physical space but as a metaphor for the mind at work, where ideas are explored, layered, and transformed through process and revision.

How does William Kentridge's work relate to global themes?

While deeply rooted in South Africa, Kentridge's exploration of power, history, memory, identity, and the human condition resonates universally. His work speaks to the impact of colonialism, political oppression, and the complexities of identity and place, themes relevant across the globe.

Final Thoughts

Exploring William Kentridge's work is a rewarding experience. It challenges you, moves you, and makes you think differently about art, history, and the world around us. Whether you're drawn to his powerful animations, his intricate prints, his large-scale theatrical works, or his thought-provoking themes, there's a depth and richness to his practice that stays with you. It's a body of work that truly embodies the idea that art is a process, a conversation with the past, and a way of making sense of the present. I hope this personal guide encourages you to explore his incredible body of work further.

If all this talk of art has you inspired, maybe it's time to find a piece that speaks to you? You can always browse art for sale right here. Or perhaps visit a museum yourself, like the one in 's-Hertogenbosch, and see what resonates with you.